Perjantanan di Yunani Kuno

Perjantanan di Yunani kuno adalah hubungan sosial yang diakui antara orang dewasa dan seorang laki-laki yang lebih muda biasanya yang masih di usia remaja.[1] Ini adalah karakteristik dari Kuno dan periode Klasik.[2] Beberapa ahli menemukan asal-usulnya dalam ritual inisiasi, terutama ritus peralihan di Kreta, di mana dikaitkan dengan pintu masuk ke dalam kehidupan militer dan agama Zeus.[3]

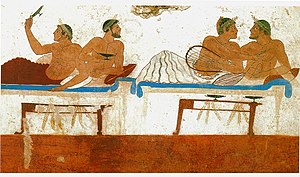

Kebiasaan sosial bernama paiderastia oleh orang Yunani yang kedua secara ideal dan dikritik dalam sastra kuno dan filsafat,[4] namun tidak adanya formalitas dalam epos-epos Homer, dan tampaknya telah dikembangkan di akhir abad ke-7 SM sebagai aspek budaya homososial Yunani,[5] yang ditandai juga dengan ketelanjangan atletik dan artistik, pernikahan yang ditunda untuk bangsawan, simposium, dan pengasingan sosial perempuan.[6] Pengaruh perjantanan begitu meluas bahwa itu telah disebut "model budaya utama untuk hubungan bebas antara warga negara."[7]

Lihat pula

Referensi

- ^ C.D.C. Reeve, Plato on Love: Lysis, Symposium, Phaedrus, Alcibiades with Selections from Republic and Laws (Hackett, 2006), p. xxi online; Martti Nissinen, Homoeroticism in the Biblical World: A Historical Perspective, translated by Kirsi Stjerna (Augsburg Fortress, 1998, 2004), p. 57 online; Nigel Blake et al., Education in an Age of Nihilism (Routledge, 2000), p. 183 online.

- ^ Nissinen, Homoeroticism in the Biblical World, p. 57; William Armstrong Percy III, "Reconsiderations about Greek Homosexualities," in Same–Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West (Binghamton: Haworth, 2005), p. 17. Sexual variety, not excluding paiderastia, was characteristic of the Hellenistic era; see Peter Green, "Sex and Classical Literature," in Classical Bearings: Interpreting Ancient Culture and History (University of California Press, 1989, 1998), p. 146 online.

- ^ Robert B. Koehl, "The Chieftain Cup and a Minoan Rite of Passage," Journal of Hellenic Studies 106 (1986) 99–110, with a survey of the relevant scholarship including that of Arthur Evans (p. 100) and others such as H. Jeanmaire and R.F. Willetts (pp. 104–105); Deborah Kamen, "The Life Cycle in Archaic Greece," in The Cambridge Companion to Archaic Greece (Cambridge University Press, 2007), pp. 91–92. Kenneth Dover, a pioneer in the study of Greek homosexuality, rejects the initiation theory of origin; see "Greek Homosexuality and Initiation," in Que(e)rying Religion: A Critical Anthology (Continuum, 1997), pp. 19–38. For Dover, it seems, the argument that Greek paiderastia as a social custom was related to rites of passage constitutes a denial of homosexuality as natural or innate; this may be to overstate or misrepresent what the initiatory theorists have said. The initiatory theory does not claim to account for the existence of homosexuality, but for formal paiderastia.

- ^ For examples, see Kenneth Dover, Greek Homosexuality (Harvard University Press, 1978, 1898), p. 165, note 18, where the eschatological value of paiderastia for the soul in Plato is noted; Paul Gilabert Barberà, "John Addington Symonds. A Problem in Greek Ethics. Plutarch's Eroticus Quoted Only in Some Footnotes? Why?" in The Statesman in Plutarch's Works (Brill, 2004), p. 303 online; and the pioneering view of Havelock Ellis, Studies in the Psychology of Sex (Philadelphia: F.A. Davis, 1921, 3rd ed.), vol. 2, p. 12 online. For Stoic "utopian" views of paiderastia, see Doyne Dawson, Cities of the Gods: Communist Utopias in Greek Thought (Oxford University Press, 1992), p. 192 online.

- ^ Thomas Hubbard, "Pindar's Tenth Olympian and Athlete-Trainer Pederasty," in Same–Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity, pp. 143 and 163 (note 37), with cautions about the term "homosocial" from Percy, p. 49, note 5.

- ^ Percy, "Reconsiderations about Greek Homosexualities," p. 17 online et passim.

- ^ Dawson, Cities of the Gods, p. 193. See also George Boys-Stones, "Eros in Government: Zeno and the Virtuous City," Classical Quarterly 48 (1998), 168–174: "there is a certain kind of sexual relationship which was considered by many Greeks to be very important for the cohesion of the city: sexual relations between men and youths. Such relationships were taken to play such an important role in fostering cohesion where it mattered — among the male population — that Lycurgus even gave them official recognition in his constitution for Sparta" (p. 169).

Daftar pustaka

- Dover, Kenneth J. Greek Homosexuality. Duckworth 1978.

- Dover, Kenneth J. "Greek Homosexuality and Initiation." In Que(e)rying Religion: A Critical Anthology. Continuum, 1997, pp. 19–38.

- Ellis, Havelock. Studies in the Psychology of Sex, vol. 2: Sexual Inversion. Project Gutenberg text

- Ferrari, Gloria. FIgures of Speech: Men and Maidens in Ancient Greece. University of Chicago Press, 2002.

- Hubbard, Thomas K. Homosexuality in Greece and Rome. University of California Press, 2003.[1] Diarsipkan 2005-12-06 di Wayback Machine.

- Johnson, Marguerite, and Ryan, Terry. Sexuality in Greek and Roman Society and Literature: A Sourcebook. Routledge, 2005.

- Lear, Andrew, and Eva Cantarella. Images of Ancient Greek Pederasty: Boys Were Their Gods. Routledge, 2008. ISBN 978-0-415-22367-6.

- Nussbaum, Martha. Sex and Social Justice. Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Percy, William A. Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece. University of Illinois Press, 1996.

- Same–Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West. Binghamton: Haworth, 2005.

- Sergent, Bernard. Homosexuality in Greek Myth. Beacon Press, 1986.