Pengguna:Crisco 1492/Geger Pacinan

| Geger Pacinan | |||

|---|---|---|---|

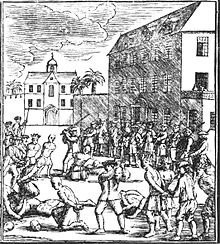

Pembunuhan tahanan Tionghoa saat pembantaian | |||

| Tanggal | 9–22 Oktober 1740, dengan berbagai pertempuran kecil setelahnya | ||

| Lokasi | Batavia, Hindia Belanda | ||

| Metode | Pogrom | ||

| Hasil | Lihat Hasil | ||

| Pihak terlibat | |||

| |||

| Jumlah korban | |||

| |||

Geger Pacinan (juga dikenal sebagai Tragedi Angke; dalam bahasa Belanda: Chinezenmoord, yang berarti "Pembunuhan orang Tionghoa") merupakan sebuah pogrom terhadap orang keturunan Tionghoa di kota pelabuhan Batavia (sekarang Jakarta) di Hindia Belanda. Kekerasan dalam batas kota berlangsung dari 9 Oktober 1740 hingga 22 Oktober; berbagai pertempuran kecil terjadi hingga akhir November.

Keresehan dalam masyarakat Tionghoa dipicu oleh represi pemerintah dan berkurangnya penghasilan akibat jatuhnya harga gula menjelang pembantaianitu. Untuk menanggapi keresehan tersebut, pada sebuah pertemuan Dewan Hindia (Raad van Indië), badan pemimpin Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie [VOC]), Guberner-Jenderal Adriaan Valckenier menyatakan bahwa kerusuhan apapun dapat ditanggapi dengan kekerasan mematikan. Pernyataan Valckenier tersebut diberlakukan pada tanggal 7 Oktober 1740 setelah ratusan orang keturunan Tionghoa, banyak di antaranya buruh di pabrik gula, membunuh 50 pasukan Belanda. Penguasa Belanda mengirim pasukan tambahan, yang mengambil semua senjata dari warga Tionghoa dan memberlakukan jam malam. Dua hari kemudian, setelah ditakutkan gosip tentang kekejaman etnis Tionghoa, kelompok etnis lain di Batavia mulai membakar rumah orang Tionghoa di sepanjang Kali Besar. Sementara, pasukan Belanda menyerang rumah orang Tionghoa dengan meriam. Kekerasan ini dengan cepat menyebar di seluruh kota Batavia sehingga lebih banyak orang Tionghoa dibunuh. Biarpun Valckenier mendeklarasi adanya pengampunan untuk orang Tionghoa pada tanggal 11 Oktober, kelompok pasukan tidak tetap terus memburu dan membunuh orang Tionghoa hingga tanggal 22 Oktober, saat Valckenier dengan tegas menyatakan bahwa pembunuhan harus dihentikan. Di luar batas kota, pasukan Belanda terus bertempur dengan buruh pabrik gula yang berbuat rusuh. Setelah beberapa minggu penuh pertempuran kecil, pasukan Belanda menyerang markas Tionghoa di berbagai pabrik gula. Orang Tionghoa yang selamat mengungsi ke Bekasi.

Diduga bahwa lebih dari 10.000 orang keturunan Tionghoa dibantai. Jumlah orang yang selamat tidak pasti; ada dugaan dari 600 sampai 3.000 yang selamat. Pada tahun berikutnya, terjadi berbagai pembantaian di seluruh pulau Jawa. Ini memicu suatu perang berdurasi dua tahun, dengan tentara gabungan Tionghoa dan Jawa melawan pasukan Belanda. Valckenier dipanggil kembali ke Belanda dan dituntut atas keterilibatannya dalam pembantaian ini; Gustaaf Willem van Imhoff menggantikannya sebagai gubernur-jenderal. Hingga zaman modern pembantaian ini kerap ditemukan dalam sastra Belanda. Pembantaian ini mungkin juga menjadi asal nama beberapa daerah di Jakarta.

Latar Belakang

Di periode awal koloniasi Hindia Belanda oleh Belanda, banyak orang keturunan Tionghoa dijadikan tukang dalam pembangunan kota Batavia di pesisir barat laut pulau Jawa;[1] mereka juga bertugas sebagai pedagang, buruh di pabrik gula, serta pemilik toko.[2] Perdagangan antara Hindia Belanda dan Tiongkok, yang berpusat di Batavia, menguatkan ekonomi dan meningkatkan imigrasi orang Tionghoa ke Jawa. Jumlah orang Tionghoa di Batavia meningkat pesat, sehingga pada tahun 1740 ada lebih dari 10.000. Ribuan lagi tinggal di luar batas kota.[3] Pemerinta kolonial Belanda mewajibkan mereka membawa surat identifikasi, dan orang yang tidak mempunyai surat tersebut dipulangkan ke Tiongkok.[4]

Kebijakan deportasi ini diketatkan pada dasawarsa 1730-an, setelah pecahnya epidemik malaria yang membunuh ribuan orang, termasuk Gubernur-Jenderal Dirk van Cloon.[4][5] Menurut sejarahwan Indonesia Benny G. Setiono, epidemik ini diikuti oleh meningkatnya rasa curiga dan dendam terhadap etnis Tionghoa, yang jumlahnya semakin banyak dan kekayaan yang semakin menonjol.[5] Akibatnya, Komisaris Urusan Orang Pribumi Roy Ferdinand, di bawah perintah Gubernur-Jenderal Adriaan Valckenier, memutuskan pada tanggal 25 Juli 1740 bahwa warga keturunan Tionghoa yang mencurigakan akan dideportasi ke Zeylan (kini Sri Lanka) dan dipaksa menjadi petani kayu manis.[5][6][7][8] Warga keturunan Tionghoa yang kaya diperas penguasa Belanda, yang mengancam mereka dengan deportasi; [5][9][10] Stamford Raffles, seorang penjelajah asal Inggris dan ahli sejarah pulau Jawa, mencatat bahwa orang Belanda diberi tahu Kapitan Cina (pemimpin etnis Tionghoa yang ditentukan Belanda) untuk Batavia, Ni Hoe Kong, agar mendeportasikan semua orang Tionghoa berpakaian hitam atau biru, sebab merekalah yang miskin.[11] Ada pula gosip bahwa orang yang dikirimkan ke Zeylan tidak pernah sampai ke sana, tetapi justru dibuang ke laut,[3][9] atau bahwa mereka mati saat membuat kerusuhan di kapal.[11] Ancaman deportasi ini membuat orang Tionghoa resah, dan banyak buruh Tionghoa meninggalkan pekerjaan mereka.[3][9]

Sementara, penduduk pribumi di Batavia, termasuk orang-orang Betawi, menjadi semakin curiga akan maksud orang Tionghoa. Masalah ekonomi ikut berperan; sebagian besar penduduk pribumi miskin, dan beranggapan bahwa orang Tionghoa tinggal di daerah-daerah terkemuka dan sejahtera.[12][13] Biarpun sejarahwan Belanda A.N. Paasman mencatat bahwa orang Tionghoa menjadi "bak orang Yahudi untuk Asia",[7] keadaan sebenarnya lebih rumit. Banyak orang Tionghoa miskin yang tinggal di sekitar Batavia merupakan buruh di pabrik gula, yang merasa dimanfaatkan para pembesar Belanda dan Tionghoa.[14] Orang Tionghoa kaya memiliki pabrik dan menjadi semakin kaya dengan mengurus perdagangan; mereka mendapatkan penghasilan dari pembuatan dan penyebaran arak, sebuah minuman keras yang dibuat dari tetes dan beras.[14][15] Namun, penguasa Belanda yang menentukan harga gula; ini juga menyebabkan keresahan.[16] Sebagai akibat penurunan harga gula di pasar dunia, yang disebabkan kenaikan jumlah ekspor ke Eropa,[17] industri gula di Hindia Belanda merugi. Hingga tahun 1740, harga gula di pasar global sudah separuh dari hargana pada tahun 1720. Karena gula menjadi salah satu ekspor utama Hindia Belanda, negara jajahan itu mengalami kesulitan finansial.[18]

Pada awalnya, beberapa anggota Dewan Hindia (Raad van Indië) beranggapan bahwa orang Tionghoa tidak mungkin menyerang Batavia,[9] dan kebijakan yang lebih tegas mengatur orang Tionghoa ditantang oleh faksi yang dipimpin mantan gubernur Zeylan Gustaaf Willem baron van Imhoff, yang kembali ke Batavia pada tahun 1738.[19][20][21] Namun, orang keturunan Tionghoa tiba di luar batas kota Batavia dari berbagai kampung, dan pada tanggal 26 September Valckenier memanggil para anggota dewan untuk pertemuan darurat. Pada pertemuan tersebut, Valckenier memerintah agar kerusuhan yang dipicu orang Tionghoa dapat ditanggapi dengan kekuatan yang mematikan.[5] Kebijakan ini terus ditantang oleh fraksi van Imhoff; Vermeulen (1938)[a] berpendapat bahwa ketegangan antara kedua fraksi politik ini ikut berperan dalam pembantaian.[6]

Pada tanggal 1 Oktober malam, Valckenier menerima laporan bahwa ribuan orang Tionghoa sudah berkumpul di luar gerbang kota Batavia; amuk mereka dipicu oleh pernyataannya pada pertemuan dewan lima hari sebelumnya. Valckenier dan anggota Dewan Hindia lain sulit percaya hal tersebut.[22] Namun, setelah orang Tionghoa membunuh seorang sarsan keturunan Bali di luar batas kota, dewan memutuskan untuk melakukan tindakan serta menguatkan jumlah pasukan yang menjaga kota.[6][23] Dua kelompok, terdiri dari 50 orang Eropa dan beberapa kuli pribumi, dikirim ke pos penjagaan di sebelah selatan dan timur Batavia,[24] dan dibuatkan rencana untuk pertempuran.[6][23]

Peristiwa

Pembantaian

After groups of Chinese sugar mill workers revolted using custom-made weapons to loot and burn mills,[14] hundreds of ethnic Chinese,[b] suspected to have been led by Chinese Captain Ni Hoe Kong,[c] killed 50 Dutch soldiers in Meester Cornelis (now Jatinegara) and Tanah Abang on 7 October.[5][10] In response, the Dutch sent 1,800 regular troops, accompanied by schutterij (militia) and eleven battalions of conscripts to stop the revolt; they established a curfew and cancelled plans for a Chinese festival.[5] Fearing that the Chinese would conspire against the colonials by candlelight, those inside the city walls were forbidden to light candles and were forced to surrender everything "down to the smallest kitchen knife".[28] The following day, the Dutch repelled an attack by up to 10,000 ethnic Chinese, led by groups from nearby Tangerang and Bekasi at the city's outer walls ;[6][29] Raffles wrote that 1,789 Chinese died in this attack.[30] In response, Valckenier called another meeting of the council on 9 October.[6][29]

Meanwhile, rumours spread among the other ethnic groups in Batavia, including slaves from Bali and Sulawesi, Bugis and Balinese troops, that the Chinese were plotting to kill, rape or enslave them.[4][31] These groups pre-emptively burned houses belonging to ethnic Chinese along Besar Stream. The Dutch followed this with an assault on Chinese settlements elsewhere in Batavia in which they burned houses and killed people. The Dutch politician and critic of colonialism W.R. van Hoëvell wrote that "pregnant and nursing women, children, and trembling old men fell on the sword. Prisoners were slaughtered like sheep".[d][32]

Troops under Lieutenant Hermanus van Suchtelen and Captain Jan van Oosten, a survivor from Tanah Abang, took station in the Chinese district: Suchtelen and his men positioned themselves at the poultry market, while van Oosten's men held a post along the nearby canal.[33] At around 5:00 p.m., the Dutch opened fire on Chinese-occupied houses with cannons, causing them to catch fire.[34][8] Some Chinese died in the burning houses, while others were shot upon leaving their homes or committed suicide in desperation. Those who reached the canal near the housing district were killed by Dutch troops waiting in small boats,[34] while other troops searched in between the rows of burning houses, killing any survivors they found.[32] These actions later spread throughout the city.[34] Vermeulen notes that many of the perpetrators were sailors and other "irregular and bad elements" of society.[e][35] During this period there was heavy looting[35]and seizures of property.[30]

The following day the violence continued to spread, and Chinese patients in a hospital were taken outside and killed.[36] Attempts to extinguish fires in areas devastated the preceding day failed, and the flames increased in vigour, and continued until 12 October.[37] Meanwhile, a group of 800 Dutch soldiers and 2,000 natives assaulted Kampung Gading Melati, where a group of Chinese survivors were holding up under the leadership of Khe Pandjang. [f][30][38][39] Setiono suggests that his actual name may have been Oie Panko.[39]}} Although the Chinese evacuated to nearby Paninggaran, they were later driven out of the area by Dutch forces. There were approximately 450 Dutch and 800 Chinese casualties in the two attacks.[30]

Kekerasan lanjutan

On 11 October Valckenier unsuccessfully requested that officers control their troops and stop the looting.[40] Two days later the council established a reward of two ducats for every Chinese head surrendered to the soldiers as an incentive for the other ethnic groups to assist in the purge.[40] As a result, ethnic Chinese who had survived the initial assault were hunted by gangs of irregulars, who killed those Chinese they found for the reward.[36] The Dutch worked with natives in different parts of Batavia; ethnic Bugis and Balinese grenadiers were sent to reinforce the Dutch on 14 October.[40] On 22 October Valckenier called for all killings to cease.[36] In a lengthy letter in which he blamed the unrest entirely on the Chinese rebels, Valckenier offered an amnesty to all Chinese, except for the leaders of the unrest, on whose heads he placed a bounty of up to 500 rijksdaalders.[41]

Outside the walls skirmishes between the Chinese rebels and the Dutch continued. On 25 October, after almost two weeks of minor skirmishes, 500 armed Chinese approached Cadouwang (now Angke), but were repelled by cavalry under the command of Ridmeester Christoffel Moll and Cornets Daniel Chits and Pieter Donker. The following day the cavalry, which consisted of 1,594 Dutch and native forces, marched on the rebel stronghold at the Salapadjang sugar mill, first gathered in the nearby woods and then set the mill on fire while the rebels were inside; another mill at Boedjong Renje was taken in the same manner by another group.[42] Fearful of the oncoming Dutch, the Chinese retreated to a sugar mill in Kampung Melayu, four hours from Salapadjang; this stronghold fell to troops under Captain Jan George Crummel. After defeating the Chinese and retaking Qual, the Dutch returned to Batavia.[43] Meanwhile, the fleeing Chinese, who were blocked to the west by 3,000 troops from the Sultanate of Banten, headed east along the north coast of Java;[44] by 30 October it was reported that the Chinese had reached Tangerang.[43]

A ceasefire order reached Crummel on 2 November, upon which he and his men returned to Batavia after stationing a contingent of 50 men at Cadouwang. When he arrived at noon there were no more Chinese stationed at the walls.[45] On 8 November the Sultanate of Cirebon requested between 2,000 and 3,000 native troops to reinforce the city guard. Looting continued until at least 28 November, and the last native troops stood down at the end of that month.[40]

Hasil

Most accounts of the massacre estimate that 10.000 Chinese were killed within Batavia's city walls, while at least another 500 were seriously wounded. Between 600 and 700 Chinese-owned houses were raided and burned.[46][47] Vermeulen gives a figure of 600 survivors,[40] while the Indonesian scholar A.R.T. Kemasang estimates that 3,000 Chinese survived.[48] The Indonesian historian Benny G. Setiono notes that 500 prisoners and hospital patients were killed,[46] and a total of 3,431 people survived.[49] The massacre was followed by an "open season"[50] against the ethnic Chinese throughout Java, causing another massacre in 1741 in Semarang, and others later in Surabaya and Gresik.[50]

As part of conditions for the cessation of violence, all of Batavia's ethnic Chinese were moved to a pecinan, or Chinatown, outside of the city walls, now known as Glodok. This allowed the Dutch to monitor the Chinese more easily.[51] To leave the pecinan, ethnic Chinese required special passes.[52] By 1743, however, ethnic Chinese had already returned to inner Batavia; several hundred merchants operated there.[3] Other ethnic Chinese led by Khe Pandjang[38] fled to Central Java where they attacked Dutch trading posts, and were later joined by troops under the command of the Javanese sultan of Mataram, Pakubuwono II. Though this further uprising was quashed in 1743,[53] conflicts in Java continued almost without interruption for the next 17 years.[2]

On 6 December 1740 van Imhoff and two fellow councillors were arrested on the orders of Valckenier for insubordination, and on 13 January 1741, they were sent to the Netherlands on separate ships;[54][55] they arrived on 19 September 1741. In the Netherlands, van Imhoff convinced the council that Valckenier was to blame for the massacre and delivered an extensive speech entitled "Consideratiën over den tegenwoordigen staat van de Ned. O.I. Comp." ("Considerations on the Current Condition of the Dutch East Indies Company") on 24 November.[56][57] As a result of the speech, the charges against him and the other councillors were dismissed.[58] On 27 October 1742 van Imhoff was sent back to Batavia on the Hersteller as the new governor-general of the East Indies, with high expectations from the Lords XVII, the leadership of the Dutch East India Company. He arrived in the Indies on 26 May 1743.[56][59][60]

Valckenier had asked to be replaced late in 1740, and in February 1741 had received a reply instructing him to appoint van Imhoff as his successor;[61] an alternative account indicates that the Lords XVII informed him that he was to be replaced by van Imhoff as punishment for exporting too much sugar and too little coffee in 1739 and thus causing large financial losses.[62][63] By the time Valckenier received the reply, van Imhoff was already on his way back to the Netherlands. Valckenier left the Indies on 6 November 1741, after appointing a temporary successor, Johannes Thedens. Taking command of a fleet, Valckenie headed for the Netherlands. On 25 January 1742 he arrived in Capetown but was detained, and investigated by governor Hendrik Swellengrebel by order of the Lords XVII. In August 1942 Valckenier was sent back to Batavia, where he was imprisoned in Fort Batavia and, three months later, tried on several charges, including his involvement in the massacre.[64] In March 1744 he was convicted and condemned to death, and all his belongings were confiscated.[65] In December 1744 the trial was reopened when Valckenier gave a lengthy statement to defend himself.[60][66][67] Valckenier asked for more evidence from the Netherlands, but died in his prison cell on 20 June 1751, before the investigation was completed. The death penalty was rescinded posthumously in 1755.[59][67] Vermeulen characterises the investigation as unfair and fuelled by popular outrage in the Netherlands,[68] and arguably this was officially recognised because in 1760 Valckenier's son, Adriaan Isaäk Valckenier, received reparations totalling 725,000 gulden.[69]

Sugar production in the area suffered greatly after the massacre, as many of the Chinese who had run the industry had been killed or were missing. It began to recover after the new governor-general, van Imhoff, "colonised" Tangerang. He initially intended for men to come from the Netherlands and work the land; he considered those already settled in the Indies to be lazy. However, he was unable to attract new settlers because of high taxes and thus sold the land to those already in Batavia. As he had expected, the new land-owners were unwilling to "soil their hands", and quickly rented out the land to ethnic Chinese.[70] Production rose steadily after this, but took until the 1760s to reach pre-1740 levels, after which it again diminished.[70][71] The number of mills also declined. In 1710 there had been 131, but by 1750 the number had fallen to 66.[15]

Pengaruh

Vermeulen menyebut pembantaian ini sebagai "salah satu peristiwa dalam kolonialisme [Belanda] pada abad ke-18 yang paling menonjol".[g][72] Dalam disertasinya, W. W. Dharmowijono menyatakan bahwa pogrom ini mempunyai peran besar dalam sastra Belanda. Sastra ini muncul dengan cepat; Dharmowijono mencatat adanya sebuah puisi oleh Willem van Haren yang mengkritik pembantaian ini (dari tahun 1742) dan sebuah puisi anonim, dari periode yang sama, yang mengkritik orang Tionghoanya.[73] Raffles menulis pada tahun 1830 bahwa catatan historis Belanda "jauh dari lengkap atau memuaskan".[h][74]

Dutch historian Leonard Blussé writes that the massacre indirectly led to the rapid expansion of Batavia, and institutionalised a modus vivendi that led to a dichotomy between the ethnic Chinese and other groups which could be felt in the late 20th century.[75] The massacre may also have been a factor in the naming of numerous areas in Jakarta. One possible etymology for the name of the Tanah Abang district (meaning "red earth") is that it was named for the Chinese blood spilled there; van Hoëvell suggests that the naming was a compromise to make the Chinese survivors accept amnesty more quickly.[76][77] The name Rawa Bangke, for a subdistrict of East Jakarta, may be derived from the vulgar Indonesian word for corpse, bangkai, due to the great number of ethnic Chinese killed there; a similar etymology has been suggested for Angke in Tambora.[76]

Lihat pula

Keterangan

- ^ Dalam Vermeulen, Johannes Theodorus (1938). De Chineezen te Batavia en de troebelen van 1740 (dalam bahasa Belanda). Leiden: Proefschrift. [6]

- ^ For example, the minor post of Qual, located near the Tangerang River and staffed by 15 soldiers, was surrounded by at least five hundred Chinese.[25]

- ^ Kong is noted as surviving both the assault and the massacre. How he did so is not known; there is speculation that he had a secret cellar under his house or that he dressed in women's clothing and hid inside the governor's castle.[26] W.R. van Hoëvell suggested that Kong gathered several hundred people after escaping the castle and hid in a Portuguese church near the Chinese quarters.[27] He was later captured and accused of leading the uprising by the Dutch but, despite being tortured, did not confess.[26]

- ^ Original: "... Zwangere vrouwen, zoogende moeders , argelooze kinderen, bevende grijsaards worden door het zwaard geveld. Den weerloozen gevangenen wordt als schapen de keel afgesneden".

- ^ Original: "... vele ongeregelde en slechte elementen ..."

- ^ Sources spell his name alternatively as Khe Pandjang, Que Pandjang, Si Pandjang, or Sie Pan Djiang.

- ^ Asli: "... markante feiten uit onze 18e-eeuwse koloniale geschiedenis tot onderwerp genomen".

- ^ Asli: "... far from complete or satisfactory."

Rujukan

- Catatan kaki

- ^ Tan 2005, hlm. 796.

- ^ a b Ricklefs 2001, hlm. 121.

- ^ a b c d Armstrong, Armstrong & Mulliner 2001, hlm. 32.

- ^ a b c Dharmowijono 2009, hlm. 297.

- ^ a b c d e f g Setiono 2008, hlm. 111–113.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dharmowijono 2009, hlm. 298.

- ^ a b Paasman 1999, hlm. 325–326.

- ^ a b Hall 1981, hlm. 357.

- ^ a b c d Pan 1994, hlm. 35–36.

- ^ a b Dharmowijono 2009, hlm. 302.

- ^ a b Raffles 1830, hlm. 234.

- ^ Raffles 1830, hlm. 233–235.

- ^ van Hoëvell 1840, hlm. 461–462.

- ^ a b c Kumar 1997, hlm. 32.

- ^ a b Dobbin 1996, hlm. 53–55.

- ^ Mazumdar 1998, hlm. 89.

- ^ Ward 2009, hlm. 98.

- ^ von Wachtel 1911, hlm. 200.

- ^ Dharmowijono 2009, hlm. 297–298.

- ^ van Hoëvell 1840, hlm. 460.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica 2011, Gustaaf Willem.

- ^ van Hoëvell 1840, hlm. 465–466.

- ^ a b van Hoëvell 1840, hlm. 466–467.

- ^ van Hoëvell 1840, hlm. 468.

- ^ van Hoëvell 1840, hlm. 473.

- ^ a b Dharmowijono 2009, hlm. 302–303.

- ^ van Hoëvell 1840, hlm. 585.

- ^ Pan 1994, hlm. 36.

- ^ a b Setiono 2008, hlm. 114.

- ^ a b c d Raffles 1830, hlm. 235.

- ^ Setiono 2008, hlm. 114–116.

- ^ a b van Hoëvell 1840, hlm. 485.

- ^ van Hoëvell 1840, hlm. 486.

- ^ a b c Setiono 2008, hlm. 117.

- ^ a b Dharmowijono 2009, hlm. 299.

- ^ a b c Setiono 2008, hlm. 118–119.

- ^ van Hoëvell 1840, hlm. 489–491.

- ^ a b Dharmowijono 2009, hlm. 301.

- ^ a b Setiono 2008, hlm. 135.

- ^ a b c d e Dharmowijono 2009, hlm. 300.

- ^ van Hoëvell 1840, hlm. 493–496.

- ^ van Hoëvell 1840, hlm. 503–506.

- ^ a b van Hoëvell 1840, hlm. 506–507.

- ^ Ricklefs 1983, hlm. 270.

- ^ van Hoëvell 1840, hlm. 506–508.

- ^ a b Setiono 2008, hlm. 119.

- ^ van Hoëvell 1840, hlm. 491–492.

- ^ Kemasang 1982, hlm. 68.

- ^ Setiono 2008, hlm. 121.

- ^ a b Kemasang 1981, hlm. 137.

- ^ Setiono 2008, hlm. 120–121.

- ^ Setiono 2008, hlm. 130.

- ^ Setiono 2008, hlm. 135–137.

- ^ Geyl 1962, hlm. 339.

- ^ van Eck 1899, hlm. 160.

- ^ a b Blok & Molhuysen 1927, hlm. 632–633.

- ^ Raat 2010, hlm. 81.

- ^ van Eck 1899, hlm. 161.

- ^ a b Setiono 2008, hlm. 125–126.

- ^ a b Geyl 1962, hlm. 341.

- ^ Vanvugt 1985, hlm. 106.

- ^ Ricklefs 2001, hlm. 124.

- ^ Raat 2010, hlm. 82.

- ^ Stellwagen 1895, hlm. 227.

- ^ Blok & Molhuysen 1927, hlm. 1220–1221.

- ^ Vanvugt 1985, hlm. 92–95, 106–107.

- ^ a b Blok & Molhuysen 1927, hlm. 1220.

- ^ Terpstra 1939, hlm. 246.

- ^ Blok & Molhuysen 1927, hlm. 1221.

- ^ a b Ota 2006, hlm. 133.

- ^ Bulbeck et al. 1998, hlm. 113.

- ^ Terpstra 1939, hlm. 245.

- ^ Dharmowijono 2009, hlm. 304.

- ^ Raffles 1830, hlm. 231.

- ^ Blussé 1981, hlm. 96.

- ^ a b Setiono 2008, hlm. 115.

- ^ van Hoëvell 1840, hlm. 510.

- Bibliografi

- Armstrong, M. Jocelyn; Armstrong, R. Warwick; Mulliner, K. (2001). Chinese Populations in Contemporary Southeast Asian Societies: Identities, Interdependence, and International Influence (dalam bahasa Inggris). Richmond: Curzon. ISBN 978-0-7007-1398-1.

- Blok, Petrus Johannes; Molhuysen, Philip Christiaan, ed. (1927). Nieuw Nederlandsch Biografisch Woordenboek (dalam bahasa Belanda) (edisi ke-ke-7). Leiden: A. W. Sijthoff. OCLC 309920700.

- Blussé, Leonard (1981). "Batavia, 1619–1740: The Rise and Fall of a Chinese Colonial Town". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies (dalam bahasa Inggris). Singapore: Cambridge University Press. 12 (1): 159–178. doi:10.1017/S0022463400005051. ISSN 0022-4634.

- Bulbeck, David; Reid, Anthony; Tan, Lay Cheng; Wu, Yiqi (1998). Southeast Asian Exports since the 14th century : Cloves, Pepper, Coffee, and Sugar (dalam bahasa Inggris). Leiden: KITLV Press. ISBN 978-981-3055-67-4.

- Dharmowijono, W. W. (2009) (dalam bahasa Belanda). Van koelies, klontongs en kapiteins: het beeld van de Chinezen in Indisch-Nederlands literair proza 1880–1950 [Mengenai Kuli, Klontong, dan Kapitan: Citra Orang Tionghoa dalam Sastra Indonesia-Belanda 1880–1950] (Tesis Dokter Humanitas). Amsterdam: Universiteit van Amsterdaam. http://dare.uva.nl/document/147345. Diakses pada 1 December 2011.

- Dobbin, Christine (1996). Asian Entrepreneurial Minorities : Conjoint Communities in the Making of the World-Economy 1570–1940 (dalam bahasa Inggris). Richmond: Curzon. ISBN 978-0-7007-0404-0.

- van Eck, Rutger (1899). "Luctor et emergo", of, de Geschiedenis der Nederlanders in den Oost-Indischen Archipel (dalam bahasa Belanda). Zwolle: Tjeenk Willink. OCLC 67507521.

- Geyl, P. (1962). Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse Stam (dalam bahasa Belanda). 4. Amsterdam: Wereldbibliotheek. ISBN 978-981-3055-67-4. OCLC 769104246.

- Hall, Daniel George Edward (1981). A History of South-East Asia (dalam bahasa Inggris) (edisi ke-ke-4, dengan gambar). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-24163-9.

- van Hoëvell, Wolter Robert (1840). "Batavia in 1740". Tijdschrift voor Neerlands Indie (dalam bahasa Belanda). Batavia. 3 (1): 447–557.

- Kemasang, A. R. T. (1981). "Overseas Chinese in Java and Their Liquidation in 1740". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies (dalam bahasa Inggris). Singapore: Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars. 19: 123–146. ISSN 0007-4810.

- Kemasang, A. R. T. (1982). "The 1740 Massacre of Chinese in Java: Curtain Raiser for the Dutch Plantation Economy". Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars (dalam bahasa Inggris). Cambridge: Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars. 14: 61–71. ISSN 0007-4810.

- Kumar, Ann (1997). Java and Modern Europe : Ambiguous Encounters (dalam bahasa Inggris). Surrey: Curzon. ISBN 978-0-7007-0433-0.

- Paasman, A. N. (1999). "Een klein aardrijkje op zichzelf, de multiculturele samenleving en de etnische literatuur". Literatuur (dalam bahasa Belanda). Utrecht. 16: 324–334. Diakses tanggal 4 December 2011.

- Pan, Lynn (1994). Sons of the Yellow Emperor: A History of the Chinese Diaspora (dalam bahasa Inggris). New York: Kodansha Globe. ISBN 978-1-56836-032-4.

- Mazumdar, Sucheta (1998). Sugar and Society in China : Peasants, Technology, and the World Market (dalam bahasa Inggris). Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-85408-6.

- Ota, Atsushi (2006). Changes of Regime and Social Dynamics in West Java : Society, State, and the outer world of Banten, 1750–1830 (dalam bahasa Inggris). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15091-1.

- Raat, Alexander (2010). The Life of Governor Joan Gideon Loten (1710–1789) : A Personal History of a Dutch Virtuoso. Hilversum: Verloren. ISBN 978-90-8704-151-9.

- Raffles, Thomas Stamford (1830) [1817]. The History of Java (dalam bahasa Inggris). 2. London: Black. OCLC 312809187.

- Ricklefs, Merle Calvin (1983). "The Crisis of 1740–1 in Java: the Javanese, Chinese, Madurese and Dutch, and the Fall of the Court of Kartasura". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (dalam bahasa Inggris). The Hague. 139 (2/3): 268–290.

- Ricklefs, Merle Calvin (2001). A History of Modern Indonesia since c. 1200 (dalam bahasa Inggris url = http://books.google.co.id/books?id=0GrWCmZoEBMC) (edisi ke-3rd). Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-4479-9.

- Setiono, Benny G. (2008). Tionghoa dalam Pusaran Politik. Jakarta: TransMedia Pustaka. ISBN 978-979-96887-4-3.

- Stellwagen, A. W. (1895). "Valckenier en Van Imhoff". Elsevier's Geïllustreerd Maandschrift (dalam bahasa Belanda). Amsterdam. 5 (1): 209–233. .

- Tan, Mely G. (2005). Ember, Melvin; Ember, Carol R. & Skoggard, Ian, ed. "Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World" (dalam bahasa Inggris). New York: Springer Science+Business Media: 795–807. ISBN 978-0-387-29904-4. Parameter

|contribution=akan diabaikan (bantuan) - Terpstra, H. (1939). M. G. De Boer, ed. "Rev. of Th. Vermeulen, De Chinezenmoord van 1740". Tijdschrift Voor Geschiedenis (dalam bahasa Belanda). Groningen: P. Noordhoff: 245–247. Diakses tanggal 2 December 2011.

- Vanvugt, Ewald (1985). Wettig opium : 350 jaar Nederlandse opiumhandel in de Indische archipel (dalam bahasa Belanda). Haarlem: In de Knipscheer. ISBN 978-90-6265-197-9.

- von Wachtel, August (1911). "The American Sugar Industry and Beet Sugar Gazette" (dalam bahasa Inggris). 13. Chicago: Beet Sugar Gazette Co: 200–203. Parameter

|contribution=akan diabaikan (bantuan) - Ward, Katy (2009). Networks of Empire : Forced Migration in the Dutch East India Company (dalam bahasa Inggris). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88586-7.

- Rujukan internet

- "Gustaaf Willem, baron van Imhoff". Encyclopædia Britannica Online (dalam bahasa Inggris). Encyclopædia Britannica. 2011. Diakses tanggal 26 October 2011.