Miniatur (naskah beriluminasi): Perbedaan antara revisi

| Baris 75: | Baris 75: | ||

The Flemish miniature did not, however, hold the favor of western Europe without a rival. That rival had arisen in the south, and had come to perfection concurrently with the miniature of the Low Countries in the 15th century. This was the Italian miniature, which passed through the same stages as the miniatures of England and France and the Low Countries. Intercommunication between the countries of Europe was too well established for the case to be otherwise. In Italian manuscripts of the normal type the influence of Byzantine art is very manifest during the 13th and 14th centuries. The old system of painting the flesh tints upon olive green or some similar pigment, which is left exposed on the lines of the features, thus obtaining a swarthy complexion, continued to be practiced in a more or less modified form into the 15th century. As a rule, the pigments used are more opaque than those employed in the northern schools; and the artist trusted more to color alone to obtain the desired effect than to the mixture of color and gold which gave such brilliant results in the diapered patterns of France. The vivid scarlet of the Italian miniaturists is peculiarly their own. The figure-drawing is less realistic than the contemporary art of English and French manuscripts, the human form being often thick-set. In general, the Italian miniature, before its great expansion in the 14th century, is far behind the miniatures of the north. But with the 15th century, under the influence of the [[Renaissance]], it advanced into the front rank and rivalled the best work of the Flemish school. The use of thicker pigments enabled the miniaturist to obtain the hard and polished surface so characteristic of his work, and to maintain sharpness of outline, without losing the depth and richness of color which compare with the same qualities in the Flemish school. |

The Flemish miniature did not, however, hold the favor of western Europe without a rival. That rival had arisen in the south, and had come to perfection concurrently with the miniature of the Low Countries in the 15th century. This was the Italian miniature, which passed through the same stages as the miniatures of England and France and the Low Countries. Intercommunication between the countries of Europe was too well established for the case to be otherwise. In Italian manuscripts of the normal type the influence of Byzantine art is very manifest during the 13th and 14th centuries. The old system of painting the flesh tints upon olive green or some similar pigment, which is left exposed on the lines of the features, thus obtaining a swarthy complexion, continued to be practiced in a more or less modified form into the 15th century. As a rule, the pigments used are more opaque than those employed in the northern schools; and the artist trusted more to color alone to obtain the desired effect than to the mixture of color and gold which gave such brilliant results in the diapered patterns of France. The vivid scarlet of the Italian miniaturists is peculiarly their own. The figure-drawing is less realistic than the contemporary art of English and French manuscripts, the human form being often thick-set. In general, the Italian miniature, before its great expansion in the 14th century, is far behind the miniatures of the north. But with the 15th century, under the influence of the [[Renaissance]], it advanced into the front rank and rivalled the best work of the Flemish school. The use of thicker pigments enabled the miniaturist to obtain the hard and polished surface so characteristic of his work, and to maintain sharpness of outline, without losing the depth and richness of color which compare with the same qualities in the Flemish school. |

||

The Italian style was followed in the manuscripts of [[Provence]] in the 14th and 15th centuries. It had its effect, too, on the school of northern France, by which it was also influenced in turn. In the manuscripts of southern Germany it is also in evidence. But the principles which have been reviewed as guiding the development of the miniature in the more important schools apply equally to all. Like the miniature of the Flemish school, the Italian miniature was still worked to some extent with success, under special patronage, even in the 16th century; but with the rapid displacement of the manuscript by the [[printing|printed book]] the miniaturist's occupation was brought to a close. |

The Italian style was followed in the manuscripts of [[Provence]] in the 14th and 15th centuries. It had its effect, too, on the school of northern France, by which it was also influenced in turn. In the manuscripts of southern Germany it is also in evidence. But the principles which have been reviewed as guiding the development of the miniature in the more important schools apply equally to all. Like the miniature of the Flemish school, the Italian miniature was still worked to some extent with success, under special patronage, even in the 16th century; but with the rapid displacement of the manuscript by the [[printing|printed book]] the miniaturist's occupation was brought to a close. --> |

||

==Persia== |

== Persia == |

||

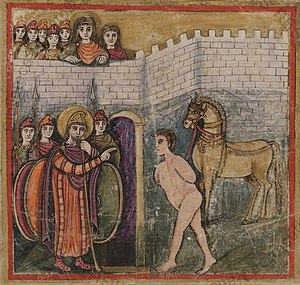

[[File:Yusef Zuleykha.jpg|thumb|left|[[Yusuf |

[[File:Yusef Zuleykha.jpg|thumb|left|[[Yusuf dan Zulaikha]] ([[Joseph (son of Jacob)|Yusuf]] dikejar-kejar oleh [[istri Potifar]]), miniatur karya [[Behzād]], 1488.]] |

||

{{main| |

{{main|Miniatur Persia}} |

||

[[Seni rupa Persia]] memiliki tradisi yang panjang dalam pembuatan miniatur. |

|||

[[Persian art]] has a long tradition of the use of miniatures. |

|||

[[Reza Abbasi]] (1565–1635), |

[[Reza Abbasi]] (1565–1635), yang dianggap sebagai salah satu pelukis Persia yang paling ternama sepanjang masa, adalah seorang spesialis miniatur yang meminati subyek-subyek alami. Kini karya-karyanya yang sintas dapat dijumpai di banyak musem besar [[dunia Barat]], misalnya Museum Seni [[Smithsonian]], [[Louvre]], dan [[Metropolitan Museum of Art]]. |

||

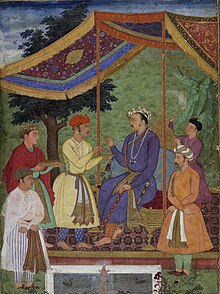

== Miniatur Mughal == |

== Miniatur Mughal == |

||

Revisi per 28 Agustus 2017 13.34

Miniatur (berasal dari bahasa Latin: minium, timbal merah) adalah ilustrasi kecil yang menghiasi naskah buatan Zaman Kuno atau Abad Pertengahan; ilustrasi-ilustrasi dalam kodeks-kodeks generasi perdana diwarnai dan dibingkai dengan pewarna merah yang terbuat dari timbal merah, sehingga kegiatan mewarnai ilustrasi disebut pula memerahkan (bahasa Latin: miniare) gambar. Ukuran gambar-gambar hiasan naskah buatan Abad Pertengahan yang umumnya kecil-kecil menyebabkan orang keliru menyangka bahwa istilah ini berarti "berukuran kecil" (bahasa Latin: minuta) atau "memperkecil" (bahasa Latin: minuare), sehingga menggunakannya sebagai sebutan bagi gambar-gambar berukuran kecil, khususnya miniatur-miniatur potret, yang juga berasal dari tradisi seni rupa yang sama dan mula-mula dibuat dengan teknik-teknik yang sama.

Selain tradisi-tradisi dunia Barat dan Bizantium, terdapat pula tradisi-tradisi miniatur Asia yang pada umumnya lebih bersifat ilustratif. Bermula sebagai hiasan naskah, gambar-gambar buatan Asia ini kelak berkembang menjadi gambar-gambar kecil pada satu halaman penuh untuk dikoleksi yang juga disebut miniatur, sementara gambar-gambar sejenis di dunia Barat yang dibuat dengan cat air dan sejumlah medium lain tidak disebut miniatur. Miniatur-miniatur Asia meliputi miniatur-miniatur buatan Persia, Mughal, Osmanli, dan India.

Artikel ini membahas tentang sejarah seni lukis miniatur, khususnya di dunia Barat. Untuk teknik pembuatannya, lihat naskah beriluminasi.

Italia dan Bizantium, abad ke-3 sampai abad ke-6

Miniatur-miniatur tertua yang masih ada sekarang ini adalah serangkaian potongan gambar atau miniatur berwarna dari Ilias Ambrosiana, sebuah naskah wiracarita Ilias dari abad ke-3.

Persia

Seni rupa Persia memiliki tradisi yang panjang dalam pembuatan miniatur.

Reza Abbasi (1565–1635), yang dianggap sebagai salah satu pelukis Persia yang paling ternama sepanjang masa, adalah seorang spesialis miniatur yang meminati subyek-subyek alami. Kini karya-karyanya yang sintas dapat dijumpai di banyak musem besar dunia Barat, misalnya Museum Seni Smithsonian, Louvre, dan Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Miniatur Mughal

Lukisan Mughal berkembang pada masa kekuasaan Kemaharajaan Mughal (abad ke-16 sampai abad ke-18), dan pada umumnya terbatas pada miniatur-miniatur, baik sebagai ilustrasi buku maupun sebagai lembaran lukisan untuk disimpan dalam album. Seni lukis Mughal bersumber dari tradisi seni lukis miniatur Persia yang diperkenalkan ke India oleh Mir Sayyid Ali dan Abd al-Samad pada pertengahan abad ke-16. Seni lukis Mughal segera tumbuh mandiri dan menjauh dari sumbernya, seni rupa Safawi; berkat pengaruh para seniman Hindu, warna-warna lukisan lambat laun tampak semakin cerah dan gambar-gambar dalam lukisan pun tampak semakin alami. Subyek lukisan lebih banyak bersifat sekular, sebagian besar berupa ilustrasi pada karya-karya sastra atau tulisan sejarah, potret-potret warga istana, dan kajian-kajian tentang alam. Pada puncak kejayaannya, lukisan-lukisan ala Mughal menampilkan suatu perpaduan yang elok dari seni rupa Persia, Eropa, dan Hindustan.

Imperium Osmanli

Pemalsuan

Miniatur-miniatur buatan Abad Pertengahan pernah dipalsukan untuk menipu kolektor, pelaku pemalsuan yang paling terkenal adalah tokoh misterius yang dijuluki Si Pemalsu Spanyol.

Lihat pula

Rujukan

Artikel ini menyertakan teks dari suatu terbitan yang sekarang berada pada ranah publik: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "perlu nama artikel ". Encyclopædia Britannica (edisi ke-11). Cambridge University Press.

Artikel ini menyertakan teks dari suatu terbitan yang sekarang berada pada ranah publik: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "perlu nama artikel ". Encyclopædia Britannica (edisi ke-11). Cambridge University Press.- Otto Pächt, Book Illumination in the Middle Ages (terjemahan dari bahasa Jerman), 1986, Harvey Miller Publishers, London, ISBN 0-19-921060-8

- Walther, Ingo F. dan Wolf, Norbert, Masterpieces of Illumination (Codices Illustres); hal. 350–353; 2005, Taschen, Köln; ISBN 3-8228-4750-X

- Jonathan Alexander; Medieval Illuminators and their Methods of Work; hal. 9, Yale UP, 1992, ISBN 0-300-05689-3

- Calkins, Robert G. Illuminated Books of the Middle Ages. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1983.

- Papadaki-Oekland Stella,Byzantine Illuminated Manuscripts of the Book of Job, ISBN 2-503-53232-2.

Bacaan tambahan

- Kren, T. & McKendrick, Scot (eds), Illuminating the Renaissance – The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe, Getty Museum/Royal Academy of Arts, 2003, ISBN 1-903973-28-7

- McKendrick, Scot; Lowden, John; Doyle, Kathleen, (editor), Royal Manuscripts, The Genius of Illumination, 2011, British Library, ISBN 978-0-7123-5815-6

- T. Voronova and A Sterligov, Western European Illuminated Manuscripts (in the St Petersberg Public Library), 2003, Sirocco, London

- Weitzmann, Kurt. Late Antique and Early Christian Book Illumination. Chatto & Windus, London (New York: George Braziller) 1977.

- Nordenfalk, Carl. Celtic and Anglo-Saxon Painting: Book illumination in the British Isles 600–800. Chatto & Windus, London (New York: George Braziller), 1977.

- Brown, Michelle P., Manuscripts from the Anglo-Saxon Age, 2007, British Library, ISBN 978-0-7123-0680-5

- Williams, John, Early Spanish Manuscript Illumination Chatto & Windus, London (New York, George Braziller), 1977.

- Cahn, Walter, Romanesque Bible Illumination, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1982, ISBN 0-8014-1446-6

Persia

- Canby, Sheila R., Persian Painting, 1993, British Museum Press, ISBN 978-0-7141-1459-0

- Titley, Norah M., Persian Miniature Painting, and its Influence on the Art of Turkey and India, 1983, University of Texas Press, ISBN 0-292-76484-7

- Welch, Stuart Cary. Royal Persian Manuscripts, Thames & Hudson, 1976, ISBN 0-500-27074-0

Kebangkitan kembali pada abad ke-19

- Sandra Hindman, Michael Camille, Nina Rowe & Rowan Watson, Manuscript Illumination in the Modern Age : Recovery and Reconstruction, Evanston : Northwestern University, 2001.

- Thomas Coomans & Jan De Maeyer (editor), The Revival of Mediaeval Illuminating in the Nineteenth Century (KADOC Artes, 9), University Press Leuven, 2007, 336 halaman.

Pranala luar

- Skriptorium Digital

- British Library, Katalog Naskah Beriluminasi

- Initiale - Catalogue de manuscrits enluminés

- Perbendaharaan Naskah Beriluminasi di Herzogenburg/Austria

- Kurzinventar der illuminierten Handschriften in Stift Stams/Austria

- The Illuminated Middle Ages. Beberapa ratus teks beriluminasi terdigitalisasi dari koleksi-koleksi Perpustakaan Nasional Perancis. (komersial)

- Menyingkap Rahasia Para Pelukis dan Iluminator Abad Pertengahan

- Lukisan Miniatur Asia Tengah

- Miniatur-miniatur Armenia (foto)