Geosentrisme: Perbedaan antara revisi

Wagino Bot (bicara | kontrib) k minor cosmetic change |

Wagino Bot (bicara | kontrib) k minor cosmetic change |

||

| Baris 7: | Baris 7: | ||

Dua pengamatan umum mendukung pandangan bahwa Bumi adalah pusat dari alam semesta. Pengamatan pertama adalah bintang-bintang, matahari dan planet-planet nampak berputar mengitari bumi setiap hari, membuat bumi adalah pusat sistem ini. Lebih lanjut, setiap bintang berada pada suatu bulatan stelar atau selestial ("''stellar sphere''" atau "''celestial sphere''"), di mana bumi adalah pusatnya, yang berkeliling setiap hari, di seputar garis yang menghubungkan kutub utara dan selatan sebagai aksisnya. Bintang-bintang yang terdekat dengan [[khatulistiwa]] nampak naik dan turun paling jauh, tetapi setiap bintang kembali ke titik terbitnya setiap hari.{{sfn|Kuhn|1957|pp=5-20}} Observasi umum kedua yang mendukung model geosentrik adalah bumi nampaknya tidak bergerak dari sudut pandang pengamat yang berada di bumi, bahwa bumi itu solid, stabil dan tetap di tempat. Dengan kata lain, benar-benar dalam posisi diam. |

Dua pengamatan umum mendukung pandangan bahwa Bumi adalah pusat dari alam semesta. Pengamatan pertama adalah bintang-bintang, matahari dan planet-planet nampak berputar mengitari bumi setiap hari, membuat bumi adalah pusat sistem ini. Lebih lanjut, setiap bintang berada pada suatu bulatan stelar atau selestial ("''stellar sphere''" atau "''celestial sphere''"), di mana bumi adalah pusatnya, yang berkeliling setiap hari, di seputar garis yang menghubungkan kutub utara dan selatan sebagai aksisnya. Bintang-bintang yang terdekat dengan [[khatulistiwa]] nampak naik dan turun paling jauh, tetapi setiap bintang kembali ke titik terbitnya setiap hari.{{sfn|Kuhn|1957|pp=5-20}} Observasi umum kedua yang mendukung model geosentrik adalah bumi nampaknya tidak bergerak dari sudut pandang pengamat yang berada di bumi, bahwa bumi itu solid, stabil dan tetap di tempat. Dengan kata lain, benar-benar dalam posisi diam. |

||

Model geosentrik biasanya dikombinasi dengan suatu Bumi yang bulat oleh filsuf Romawi kuno dan abad pertengahan. Ini tidak sama dengan pandangan model [[Bumi datar]] yang disiratkan dalam sejumlah [[mitologi]], sebagaimana juga dalah kosmologi kitab-kitab suci dan Latin kuno.{{refn|group=n|Alam semesta Mesir secara isi sama dengan alam semesta Babel, yaitu digambarkan seperti kotak persegi panjang dengan orientasi utara-selatan dan dengn permukaan sedikit cembung, di mana Mesir adalah pusatnya. Pandangan astronomi Ibrani kuno yang serupa dapat dilihat dari tulisan-tulisan kitab suci, misalnya teori penciptaan semesta dan berbagai [[mazmur]] yang menyebut "cakrawala", bintang-bintang, matahari dan bumi. Orang Ibrani memandang bumi seakan-akan sebagai permukaan datar yang terdiri dari bagian padat dan cair, dan langit sebagai alam cahaya di mana benda-benda langit bergerak. Bumi ditopang oleh batu-batu penjuru dan tidak dapat digerakkan selain oleh [[Yahweh]] (misalnya dalam kaitan dengan gempa bumi). Menurut orang Ibrani, matahari dan bulan berjarak dekat satu sama lain<ref>{{cite book |

Model geosentrik biasanya dikombinasi dengan suatu Bumi yang bulat oleh filsuf Romawi kuno dan abad pertengahan. Ini tidak sama dengan pandangan model [[Bumi datar]] yang disiratkan dalam sejumlah [[mitologi]], sebagaimana juga dalah kosmologi kitab-kitab suci dan Latin kuno.{{refn|group=n|Alam semesta Mesir secara isi sama dengan alam semesta Babel, yaitu digambarkan seperti kotak persegi panjang dengan orientasi utara-selatan dan dengn permukaan sedikit cembung, di mana Mesir adalah pusatnya. Pandangan astronomi Ibrani kuno yang serupa dapat dilihat dari tulisan-tulisan kitab suci, misalnya teori penciptaan semesta dan berbagai [[mazmur]] yang menyebut "cakrawala", bintang-bintang, matahari dan bumi. Orang Ibrani memandang bumi seakan-akan sebagai permukaan datar yang terdiri dari bagian padat dan cair, dan langit sebagai alam cahaya di mana benda-benda langit bergerak. Bumi ditopang oleh batu-batu penjuru dan tidak dapat digerakkan selain oleh [[Yahweh]] (misalnya dalam kaitan dengan gempa bumi). Menurut orang Ibrani, matahari dan bulan berjarak dekat satu sama lain<ref>{{cite book|chapter= Cosmology|title= Encyclopedia Americana|publisher= Grolier|edition= Online|year= 2012|first= Giorgio|last= Abetti}}</ref>}}{{refn|group=n|Gambaran alam semesta dalam teks-teks Talmud adalah bumi di tengah ciptaan dengan langit sebagai bulatan yang dibentangkan di atasnya. Bumi biasanya digambarkan seperti sebuah piring yang dikelilingi oleh air. Yang menarik spekulasi kosmologi dan metafisika tidak ditanamkan dalam publik maupun dilestarikan dalam tulisan. Namun, dianggap lebih sebagai "rahasia-rahasia [[Taurat]] yang tidak seharusnya diturunkan semua orang dan kalangan" (Ketubot 112a). Meskipun studi penciptaan Allah tidak dilarang, spekulasi tentang "apa yang ada di atas, di bawah, yang ada sebelumnya dan yang kemudian" (Mishnah Hagigah: 2) dibatasi hanya untuk elite intelektual.<ref>{{cite book|chapter= Topic Overview: Judaism|title= Encyclopedia of Science and Religion|editor-first=J. Wentzel Vrede|editor-last= van Huyssteen|volume= 2|location= New York|publisher= Macmillan Reference USA|year= 2003|pages= 477–83|first= Hava|last= Tirosh-Samuelson}}</ref>}}{{refn|group=n|Sebagaimana Midrash dan Talmud, Targum tidak berpandangan adanya suatu bulatan bumi, melainkan suatu piringan bumi datar, yang dikitari matahari dalam jalur setengah lingkaran yang ditempuh rata-rata dalam 12 jam.<ref>{{cite journal |title= The distribution of land and sea on the Earth's surface according to Hebrew sources |first= Solomon |last= Gandz |journal= Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research |volume= 22 |year= 1953 |pages= 23–53}}</ref>}}<!-- The ancient Jewish [[Celestial cartography|uranography]] pictured a flat Earth over which was put a dome-shaped rigid canopy, named firmament (רקיע- rāqîa').{{refn|group=n|"firmament - The division made by God, according to the P account of creation, to restrain the cosmic water and form the sky (Gen. 1: 6-8). Hebrew cosmology pictured a flat earth, over which was a dome-shaped firmament, supported above the earth by mountains, and surrounded by waters. Holes or sluices (windows, Gen. 7: 11) allowed the water to fall as rain. The firmament was the heavens in which God set the sun (Ps. 19: 4) and the stars (Gen. 1: 14) on the fourth day of the creation. There was more water under the earth (Gen. 1: 7) and during the Flood the two great oceans joined up and covered the earth; sheol was at the bottom of the earth (Isa. 14: 9; Num. 16: 30)."<ref>{{cite book |chapter= firmament |title= Dictionary of the Bible |first= W. R. F. |last= Browning |publisher= Oxford University Press |year= 1997 |edition= Oxford Reference Online}}</ref>}}{{refn|group=n|The cosmographical structure assumed by this text is the ancient, traditional flat earth model that was common throughout the Near East and that persisted in Jewish tradition because of its place in the religiously authoritative biblical materials.<ref>{{cite book |title= The Early History Of Heaven |first= J. Edward |last= Wright |publisher= Oxford University Press |year= 2000 |page= 155 |ref={{Harvid|Wright|2000}}}}</ref>}}{{refn|group=n|“The term "firmament" (רקיע- rāqîa') denotes the atmosphere between the heavenly realm and the earth (Gen. 1:6-7, 20) where the celestial bodies move (Gen. 1:14-17). It can also be used as a synonym for "heaven" (Gen. 1:8; Ps. 19:2). This "firmament is part of the heavenly structure whether it is the equivalent of "heaven/sky" or is what separates it from the earth. […] The ancient Israelites also used more descriptive terms for how God created the celestial realm, and based on the collection of these more specific and illustrative terms, I would propose that they had two basic ideas of the composition of the heavenly realm. First is the idea that the heavenly realm was imagined as a vast cosmic canopy. The verb used to describe metaphorically how God stretched out this canopy over earth is הטנ (nātāh) "stretch out," or "spread." "I made the earth, and created humankind upon it; it was my hands that stretched out the heavens, and I commanded all their host (Isa. 45:12)." In the Bible this verb is used to describe the stretching out (pitching) of a tent. Since the texts that mention the stretching out of the sky are typically drawing on creation imagery, it seems that the figure intends to suggest that the heavens are Yahweh's cosmic tent. One can imagine ancient Israelites gazing up to the stars and comparing the canopy of the sky to the roofs of the tents under which they lived. In fact, if one were to look up at the ceiling of a dark tent with small holes in the roof during the daytime, the roof, with the sunlight shining through the holes, would look very much like the night sky with all its stars. The second image of the material composition of the heavenly realm involves a firm substance. The term רקיע (răqîa'), typically translated "firmament," indicates the expanse above the earth. The root רקע means "stamp out" or "forge." The idea of a solid, forged surface fits well with Ezekiel 1 where God's throne rests upon the רקיע (răqîa'). According to Genesis 1, the רקיע(rāqîa') is the sphere of the celestial bodies (Gen. 1:6-8, 14-17; cf. ben Sira 43:8). It may be that some imagined the עיקר to be a firm substance on which the celestial bodies rode during their daily journeys across the sky.”<ref>{{harvnb|Wright|2000|pp=55–6}}</ref>}}{{refn|group=n|In the course of the Second Temple Period Jews, and eventually Christians, began to describe the universe in new terms. The model of the universe inherited form the Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East of a flat earth completely surrounded by water with a heavenly realm of the gods arching above from horizon to horizon became obsolete. In the past the heavenly realm was for gods only. It was the place where all events on earth were determined by the gods, and their decisions were irrevocable. The gulf between the gods and humans could not have been greater. The evolution of Jewish cosmography in the course of the Second Temple Period followed developments in Hellenistic astronomy.<ref>{{harvnb|Wright|2000|p=201}}</ref>}}{{refn|group=n|What is described in Genesis 1:1 to 2:3 was the commonly accepted structure of the universe from at least late in the second millennium BCE to the fourth or third century BCE. It represents a coherent model for the experiences of the people of Mesopotamia through that period. It reflects a world-view that made sense of water coming from the sky and the ground as well as the regular apparent movements of the stars, sun, moon, and planets. There is a clear understanding of the restrictions on breeding between different species of animals and of the way in which human beings had gained control over what were, by then, domestic animals. There is also recognition of the ability of humans to change the environment in which they lived. This same understanding occurred also in the great creation stories of Mesopotamia; these stories formed the basis for the Jewish theological reflections of the Hebrew Scriptures concerning the creation of the world. The Jewish priests and theologians who constructed the narrative took accepted ideas about the structure of the world and reflected theologically on them in the light of their experience and faith. There was never any clash between Jewish and Babylonian people about the structure of the world, but only about who was responsible for it and its ultimate theological meaning. The envisaged structure is simple: Earth was seen as being situated in the middle of a great volume of water, with water both above and below Earth. A great dome was thought to be set above Earth (like an inverted glass bowl), maintaining the water above Earth in its place. Earth was pictured as resting on foundations that go down into the deep. These foundations secured the stability of the land as something that is not floating on the water and so could not be tossed about by wind and wave. The waters surrounding Earth were thought to have been gathered together in their place. The stars, sun, moon, and planets moved in their allotted paths across the great dome above Earth, with their movements defining the months, seasons, and year.<ref>{{cite book |chapter= Biblical Geology |title= Encyclopedia of Geology |editor1-first= Richard C. |editor1-last= Selley |editor2-first= L. Robin M. |editor2-last= Cocks |editor3-first= Ian R. |editor3-last= Plimer |volume= 1 |location= Amsterdam |publisher= Elsevier |year= 2005 |page= 253 |via= Gale Virtual Reference Library |accessdate= 2012-09-15}}</ref>}}{{refn|group=n|From Myth to Cosmos: The earliest speculations about the origin and nature of the world took the form of religious myths. Almost all ancient cultures developed cosmological stories to explain the basic features of the cosmos: Earth and its inhabitants, sky, sea, sun, moon, and stars. For example, for the Babylonians, the creation of the universe was seen as born from a primeval pair of human-like gods. In early Egyptian cosmology, eclipses were explained as the moon being swallowed temporarily by a sow or as the sun being attacked by a serpent. For the early Hebrews, whose account is preserved in the biblical book of Genesis, a single God created the universe in stages within the relatively recent past. Such pre-scientific cosmologies tended to assume a flat Earth, a finite past, ongoing active interference by deities or spirits in the cosmic order, and stars and planets (visible to the naked eye only as points of light) that were different in nature from Earth.<ref>{{cite book |last= Applebaum |first= Wilbur |chapter= Astronomy and Cosmology: Cosmology |title= Scientific Thought: In Context |editor1-first= K. Lee |editor1-last=Lerner |editor2-first= Brenda Wilmoth |editor2-last= Lerner |volume= 1 |location= Detroit |publisher= Gale |year= 2009 |pages= 20–31 |via= Gale Virtual Reference Library |accessdate= 2012-09-15}}</ref>}} |

||

However, the ancient Greeks believed that the motions of the planets were circular and not elliptical, a view that was not challenged in [[Western culture]] until the 17th century through the synthesis of theories by [[Nicolaus Copernicus|Copernicus]] and [[Johannes Kepler|Kepler]]. |

However, the ancient Greeks believed that the motions of the planets were circular and not elliptical, a view that was not challenged in [[Western culture]] until the 17th century through the synthesis of theories by [[Nicolaus Copernicus|Copernicus]] and [[Johannes Kepler|Kepler]]. |

||

| Baris 59: | Baris 59: | ||

Dikarenakan dominansi ilmiah sistem Ptolemaik dalam astronomi Islam, para astronom Muslim menerima bulat model geosentrik.{{refn|group=n|"Semua astronom Islam dari Thabit ibn Qurra pada abad ke-9 sampai Ibn al-Shatir pada abad ke-14, dan semua filsuf alamiah dari al-Kindi sampai Averroes dan seterusnya, diketahui telah menerima ... gambaran dunia menurut budaya Yunani yang terdiri dari dua bulatan, di mana salah satunya, bulatan selestial ... secara bulat membungkus yang lain."<ref>{{cite journal |first= A. I. |last= Sabra |title= Configuring the universe: Aporetic, problem solving, and kinematic modeling as themes of Arabic astronomy |journal= Perspectives on Science |volume= 6 |issue= 3 |year= 1998 |pages= 317–8}}</ref>}} |

Dikarenakan dominansi ilmiah sistem Ptolemaik dalam astronomi Islam, para astronom Muslim menerima bulat model geosentrik.{{refn|group=n|"Semua astronom Islam dari Thabit ibn Qurra pada abad ke-9 sampai Ibn al-Shatir pada abad ke-14, dan semua filsuf alamiah dari al-Kindi sampai Averroes dan seterusnya, diketahui telah menerima ... gambaran dunia menurut budaya Yunani yang terdiri dari dua bulatan, di mana salah satunya, bulatan selestial ... secara bulat membungkus yang lain."<ref>{{cite journal |first= A. I. |last= Sabra |title= Configuring the universe: Aporetic, problem solving, and kinematic modeling as themes of Arabic astronomy |journal= Perspectives on Science |volume= 6 |issue= 3 |year= 1998 |pages= 317–8}}</ref>}} |

||

Pada abad ke-12, [[Abū Ishāq Ibrāhīm al-Zarqālī|Arzachel]] meninggalkan ide Yunani kuno "pergerakan melingkar uniform" (''[[uniform circular motion]]'') dengan membuat hipotesis bahwa planet [[Merkurius]] bergerak dalam orbit eliptik,<ref name= "Rufus1939">{{Cite journal |title= The influence of Islamic astronomy in Europe and the far east |last= Rufus |first= W. C. |journal= Popular Astronomy |volume= 47 |issue= 5 |date=May 1939 |pages= 233–8}}</ref><ref name= "Hartner1955">{{cite journal |first= Willy |last= Hartner |title= The Mercury horoscope of Marcantonio Michiel of Venice |journal= Vistas in Astronomy |volume= 1 |year= 1955 |pages= 118–22}}</ref> sedangkan [[Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji|Alpetragius]] mengusulkan model planetari yang meninggalkan [[equant]], mekanisme epicycle dan eksentrik,<ref name= "Goldstein1972"/> meskipun ini menghasilkan suatu sistem yang lebih kurang akurat secara matematik.<ref name= "Gale">{{Cite book |

Pada abad ke-12, [[Abū Ishāq Ibrāhīm al-Zarqālī|Arzachel]] meninggalkan ide Yunani kuno "pergerakan melingkar uniform" (''[[uniform circular motion]]'') dengan membuat hipotesis bahwa planet [[Merkurius]] bergerak dalam orbit eliptik,<ref name= "Rufus1939">{{Cite journal |title= The influence of Islamic astronomy in Europe and the far east |last= Rufus |first= W. C. |journal= Popular Astronomy |volume= 47 |issue= 5 |date=May 1939 |pages= 233–8}}</ref><ref name= "Hartner1955">{{cite journal |first= Willy |last= Hartner |title= The Mercury horoscope of Marcantonio Michiel of Venice |journal= Vistas in Astronomy |volume= 1 |year= 1955 |pages= 118–22}}</ref> sedangkan [[Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji|Alpetragius]] mengusulkan model planetari yang meninggalkan [[equant]], mekanisme epicycle dan eksentrik,<ref name= "Goldstein1972"/> meskipun ini menghasilkan suatu sistem yang lebih kurang akurat secara matematik.<ref name= "Gale">{{Cite book|chapter= Ptolemaic Astronomy, Islamic Planetary Theory, and Copernicus's Debt to the Maragha School|title= Science and Its Times|publisher= [[Thomson Gale]]|year= 2006}}</ref> [[Fakhr al-Din al-Razi]] (1149–1209), sehubungan dengan konsepsi fisika dan dunia fisika dalam karyanya ''Matalib'', menolak pandangan Aristotelian dan Avicennian bahwa Bumi berada di pusat alam semesta, melainkan berpendapat bahwa ada "ribuan-ribuan dunia (''alfa alfi 'awalim'') di luar dunia ini sedemikian sehingga setiap dunia ini lebih besar dan masif dari dunia ini serta serupa dengan dunia ini." Untuk mendukung argumen teologinya, ia mengutip dari [[Al Quran]], "All praise belongs to God, Lord of the Worlds," menekankan istilah "Worlds" (''dunia-dunia'').<ref name= "Setia2004"/> |

||

<!-- |

<!-- |

||

The "Maragha Revolution" refers to the Maragha school's revolution against Ptolemaic astronomy. The "Maragha school" was an astronomical tradition beginning in the [[Maragheh observatory|Maragha observatory]] and continuing with astronomers from the [[Umayyad Mosque|Damascus mosque]] and [[Ulugh Beg Observatory|Samarkand observatory]]. Like their [[Al-Andalus|Andalusian]] predecessors, the Maragha astronomers attempted to solve the [[equant]] problem (the circle around whose circumference a planet or the center of an [[epicycle]] was conceived to move uniformly) and produce alternative configurations to the Ptolemaic model without abandoning geocentrism. They were more successful than their Andalusian predecessors in producing non-Ptolemaic configurations which eliminated the equant and eccentrics, were more accurate than the Ptolemaic model in numerically predicting planetary positions, and were in better agreement with empirical observations.<ref name= "Saliba1994">{{cite book |last= Saliba |first= George |authorlink= George Saliba |year= 1994 |title= A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam |pages= 233–234, 240 |publisher= [[New York University Press]] |isbn= 0814780237}}</ref> The most important of the Maragha astronomers included [[Mo'ayyeduddin Urdi]] (d. 1266), [[Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī]] (1201–1274), [[Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi]] (1236–1311), [[Ibn al-Shatir]] (1304–1375), [[Ali Qushji]] (c. 1474), [[Al-Birjandi]] (d. 1525), and Shams al-Din al-Khafri (d. 1550).<ref name= "Dallal1999">{{cite book |first= Ahmad |last= Dallal |year= 1999 |chapter= Science, Medicine and Technology |title= The Oxford History of Islam |page= 171 |editor-first= John |editor-last= Esposito |editor-link= John Esposito |location= New York |publisher= [[Oxford University Press]]}}</ref> [[Ibn al-Shatir]], the Damascene astronomer (1304–1375 AD) working at the [[Umayyad Mosque]], wrote a major book entitled ''Kitab Nihayat al-Sul fi Tashih al-Usul'' (''A Final Inquiry Concerning the Rectification of Planetary Theory'') on a theory which departs largely from the Ptolemaic system known at that time. In his book, "Ibn al-Shatir, an Arab astronomer of the fourteenth century," E. S. Kennedy wrote "what is of most interest, however, is that Ibn al-Shatir's lunar theory, except for trivial differences in parameters, is identical with that of [[Nicolaus Copernicus|Copernicus]] (1473–1543 AD)." The discovery that the models of Ibn al-Shatir are mathematically identical to those of Copernicus suggests the possible transmission of these models to Europe.<ref name= "Guessoun2008">{{cite journal |last= Guessoum |first= N. |date=June 2008 |title= Copernicus and Ibn Al-Shatir: Does the Copernican revolution have Islamic roots? |journal= The Observatory |volume= 128 |pages= 231–9}}</ref> At the Maragha and [[Ulugh Beg Observatory|Samarkand observatories]], the [[Earth's rotation]] was discussed by al-Tusi and [[Ali Qushji]] (b. 1403); the arguments and evidence they used resemble those used by Copernicus to support the Earth's motion.<ref name= "Ragep2001a">{{Cite journal |last= Ragep |first= F. Jamil |year= 2001 |title= Tusi and Copernicus: The Earth's motion in context |journal= Science in Context |volume= 14 |issue= 1-2 |pages= 145–163 |publisher= [[Cambridge University Press]]}}</ref> |

The "Maragha Revolution" refers to the Maragha school's revolution against Ptolemaic astronomy. The "Maragha school" was an astronomical tradition beginning in the [[Maragheh observatory|Maragha observatory]] and continuing with astronomers from the [[Umayyad Mosque|Damascus mosque]] and [[Ulugh Beg Observatory|Samarkand observatory]]. Like their [[Al-Andalus|Andalusian]] predecessors, the Maragha astronomers attempted to solve the [[equant]] problem (the circle around whose circumference a planet or the center of an [[epicycle]] was conceived to move uniformly) and produce alternative configurations to the Ptolemaic model without abandoning geocentrism. They were more successful than their Andalusian predecessors in producing non-Ptolemaic configurations which eliminated the equant and eccentrics, were more accurate than the Ptolemaic model in numerically predicting planetary positions, and were in better agreement with empirical observations.<ref name= "Saliba1994">{{cite book |last= Saliba |first= George |authorlink= George Saliba |year= 1994 |title= A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam |pages= 233–234, 240 |publisher= [[New York University Press]] |isbn= 0814780237}}</ref> The most important of the Maragha astronomers included [[Mo'ayyeduddin Urdi]] (d. 1266), [[Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī]] (1201–1274), [[Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi]] (1236–1311), [[Ibn al-Shatir]] (1304–1375), [[Ali Qushji]] (c. 1474), [[Al-Birjandi]] (d. 1525), and Shams al-Din al-Khafri (d. 1550).<ref name= "Dallal1999">{{cite book |first= Ahmad |last= Dallal |year= 1999 |chapter= Science, Medicine and Technology |title= The Oxford History of Islam |page= 171 |editor-first= John |editor-last= Esposito |editor-link= John Esposito |location= New York |publisher= [[Oxford University Press]]}}</ref> [[Ibn al-Shatir]], the Damascene astronomer (1304–1375 AD) working at the [[Umayyad Mosque]], wrote a major book entitled ''Kitab Nihayat al-Sul fi Tashih al-Usul'' (''A Final Inquiry Concerning the Rectification of Planetary Theory'') on a theory which departs largely from the Ptolemaic system known at that time. In his book, "Ibn al-Shatir, an Arab astronomer of the fourteenth century," E. S. Kennedy wrote "what is of most interest, however, is that Ibn al-Shatir's lunar theory, except for trivial differences in parameters, is identical with that of [[Nicolaus Copernicus|Copernicus]] (1473–1543 AD)." The discovery that the models of Ibn al-Shatir are mathematically identical to those of Copernicus suggests the possible transmission of these models to Europe.<ref name= "Guessoun2008">{{cite journal |last= Guessoum |first= N. |date=June 2008 |title= Copernicus and Ibn Al-Shatir: Does the Copernican revolution have Islamic roots? |journal= The Observatory |volume= 128 |pages= 231–9}}</ref> At the Maragha and [[Ulugh Beg Observatory|Samarkand observatories]], the [[Earth's rotation]] was discussed by al-Tusi and [[Ali Qushji]] (b. 1403); the arguments and evidence they used resemble those used by Copernicus to support the Earth's motion.<ref name= "Ragep2001a">{{Cite journal |last= Ragep |first= F. Jamil |year= 2001 |title= Tusi and Copernicus: The Earth's motion in context |journal= Science in Context |volume= 14 |issue= 1-2 |pages= 145–163 |publisher= [[Cambridge University Press]]}}</ref> |

||

| Baris 76: | Baris 76: | ||

In 1543, the geocentric system met its first serious challenge with the publication of [[Copernicus|Copernicus']] ''[[De revolutionibus orbium coelestium]]'' (''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres''), which posited that the Earth and the other planets instead revolved around the Sun. The geocentric system was still held for many years afterwards, as at the time the Copernican system did not offer better predictions than the geocentric system, and it posed problems for both [[natural philosophy]] and scripture. The Copernican system was no more accurate than Ptolemy's system, because it still used circular orbits. This was not altered until [[Johannes Kepler]] postulated that they were elliptical (Kepler's [[Kepler's laws of planetary motion#First Law|first law of planetary motion]]). |

In 1543, the geocentric system met its first serious challenge with the publication of [[Copernicus|Copernicus']] ''[[De revolutionibus orbium coelestium]]'' (''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres''), which posited that the Earth and the other planets instead revolved around the Sun. The geocentric system was still held for many years afterwards, as at the time the Copernican system did not offer better predictions than the geocentric system, and it posed problems for both [[natural philosophy]] and scripture. The Copernican system was no more accurate than Ptolemy's system, because it still used circular orbits. This was not altered until [[Johannes Kepler]] postulated that they were elliptical (Kepler's [[Kepler's laws of planetary motion#First Law|first law of planetary motion]]). |

||

--> |

--> |

||

Dengan penemuan [[teleskop]] pada tahun 1609, pengamatan yang dilakukan oleh [[Galileo Galilei]] (antara lain bahwa [[Yupiter]] memiliki sejumlah bulan) mempertanyakan sejumlah prinsip geosentrisme tetapi tidak secara serius mengancamnya. Karena ia mengamati adanya "titik-titik" gelap pada Bulan, kawah-kawah, ia berkomentar bahwa Bulan bukanlah benda langit sempurna sebagaimana anggapan sebelumnya. Ini pertama kalinya orang dapat melihat cacat pada suatu benda langit yang dianggap terbuat dari [[aether]] yang sempurna. Sedemikian, karena cacatnya bulan sekarang dapat dikaitkan dengan apa yang dilihat di Bumi, orang dapat berargumen bahwa keduanya tidak unik, melainkan terbuat dari bahan yang serupa. Galileo juga dapat melihat bulan-bulan yang mengitari Yupiter, yang didedikasikannya kepada [[:en:Cosimo II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany|Cosimo II de' Medici]], dan menyatakan bahwa bulan-bulan itu mengorbit Yupiter, bukan Bumi.<ref name= "Finocchiaro2008">{{cite book |

Dengan penemuan [[teleskop]] pada tahun 1609, pengamatan yang dilakukan oleh [[Galileo Galilei]] (antara lain bahwa [[Yupiter]] memiliki sejumlah bulan) mempertanyakan sejumlah prinsip geosentrisme tetapi tidak secara serius mengancamnya. Karena ia mengamati adanya "titik-titik" gelap pada Bulan, kawah-kawah, ia berkomentar bahwa Bulan bukanlah benda langit sempurna sebagaimana anggapan sebelumnya. Ini pertama kalinya orang dapat melihat cacat pada suatu benda langit yang dianggap terbuat dari [[aether]] yang sempurna. Sedemikian, karena cacatnya bulan sekarang dapat dikaitkan dengan apa yang dilihat di Bumi, orang dapat berargumen bahwa keduanya tidak unik, melainkan terbuat dari bahan yang serupa. Galileo juga dapat melihat bulan-bulan yang mengitari Yupiter, yang didedikasikannya kepada [[:en:Cosimo II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany|Cosimo II de' Medici]], dan menyatakan bahwa bulan-bulan itu mengorbit Yupiter, bukan Bumi.<ref name= "Finocchiaro2008">{{cite book|last= Finocchiaro|first= Maurice A.|title= The Essential Galileo|location= Indianapolis, IL|publisher= Hackett |year= 2008|page= 49}}</ref> Ini merupakan klaim signifikan karena jika benar, berarti tidak semua benda langit mengitari Bumi, menghancurkan kepercayaan teologi dan ilmiah yang dianut sebelumnya. Namun, teori-teori Galileo yang menantang geosentrisme alam semesta dibungkam oleh pihak gereja dan sikap skeptik umum terhadap sistem yang tidak menempatkan Bumi di pusat semesta, mempertahankan pikiran dan sistem Ptolemaeus dan Aristoteles. |

||

[[File:Phases-of-Venus.svg|thumb|Fase-fase planet Venus]] |

[[File:Phases-of-Venus.svg|thumb|Fase-fase planet Venus]] |

||

| Baris 105: | Baris 105: | ||

Model Ptolemaik mengenai tata surya masih terus dianut sampai ke awal zaman modern. Sejak akhir abad ke-16 dan seterusnya perlahan-lahan digantikan sebagai penggambaran konsensus oleh model heliosentrisme. Geosentrisme sebagai suatu kepercayaan agamawi terpisah, tidak pernah padam. Di Amerika Serikat antara tahun 1870-1920, misalnya, berbagai anggota [[Gereja Lutheran – Sinode Missouri]] menerbitkan artikel-artikel yang menyerang sistem astronomi Kopernikan, dan geosentrisme banyak diajarkan di dalam sinode dalam periode tersebut.<ref name= "Babinski1995">{{cite journal |editor-last= Babinski |editor-first= E. T. |journal= Cretinism of Evilution |issue= 2 |title= Excerpts from Frank Zindler's 'Report from the center of the universe' and 'Turtles all the way down' |url= http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/ce/2/part3.html |publisher= [[TalkOrigins Archive]] |year= 1995 |accessdate= 2013-12-01}}</ref> Namun, pada tahun 1902 ''Theological Quarterly'', A. L. Graebner menyatakan bahwa sinode itu tidak mempunyai posisi doktrinal terhadap geosentrisme, heliosentrisme, atau model ilmiah lainnya, kecuali kalau itu bertolak belakang dengan [[Alkitab]]. Ia menyatakan pula bahwa deklarasi apapun yang dikemukakan para penganut geosentrisme di dalam sinode bukan merupakan pendapat badan gereja secara keseluruhan.<ref name= "Graebner1902">{{cite journal |title= Science and the church |journal= Theological Quarterly |first= A. L. |last= Graebner |pages= [http://books.google.com/books?id=cxsRAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA37 37–45] |year= 1902 |publisher= Lutheran Synod of Missouri, Ohio and other states, Concordia Publishing |location= St. Louis, MO |volume= 6}}</ref> |

Model Ptolemaik mengenai tata surya masih terus dianut sampai ke awal zaman modern. Sejak akhir abad ke-16 dan seterusnya perlahan-lahan digantikan sebagai penggambaran konsensus oleh model heliosentrisme. Geosentrisme sebagai suatu kepercayaan agamawi terpisah, tidak pernah padam. Di Amerika Serikat antara tahun 1870-1920, misalnya, berbagai anggota [[Gereja Lutheran – Sinode Missouri]] menerbitkan artikel-artikel yang menyerang sistem astronomi Kopernikan, dan geosentrisme banyak diajarkan di dalam sinode dalam periode tersebut.<ref name= "Babinski1995">{{cite journal |editor-last= Babinski |editor-first= E. T. |journal= Cretinism of Evilution |issue= 2 |title= Excerpts from Frank Zindler's 'Report from the center of the universe' and 'Turtles all the way down' |url= http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/ce/2/part3.html |publisher= [[TalkOrigins Archive]] |year= 1995 |accessdate= 2013-12-01}}</ref> Namun, pada tahun 1902 ''Theological Quarterly'', A. L. Graebner menyatakan bahwa sinode itu tidak mempunyai posisi doktrinal terhadap geosentrisme, heliosentrisme, atau model ilmiah lainnya, kecuali kalau itu bertolak belakang dengan [[Alkitab]]. Ia menyatakan pula bahwa deklarasi apapun yang dikemukakan para penganut geosentrisme di dalam sinode bukan merupakan pendapat badan gereja secara keseluruhan.<ref name= "Graebner1902">{{cite journal |title= Science and the church |journal= Theological Quarterly |first= A. L. |last= Graebner |pages= [http://books.google.com/books?id=cxsRAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA37 37–45] |year= 1902 |publisher= Lutheran Synod of Missouri, Ohio and other states, Concordia Publishing |location= St. Louis, MO |volume= 6}}</ref> |

||

Artikel-artikel yang mendukung geosentrisme sebagai pandangan Alkitab muncul pada sejumlah surat kabar sains penciptaan yang berhubungan dengan [[Creation Research Society]]. Umumnya menunjuk kepada beberapa nas [[Alkitab]], yang secara harfiah mengindikasikan pergerakan harian Matahari dan Bulan yang dapat diamati mengelilingi Bumi, bukan karena rotasi Bumi pada aksisnya, misalnya pada {{Alkitab|Yosua 10:12}} di mana Matahari dan Bulan dikatakan berhenti di langit, dan {{Alkitab|Mazmur 93:1}} di mana dunia digambarkan tidak bergerak.<ref name= "Numbers1993">{{cite book |

Artikel-artikel yang mendukung geosentrisme sebagai pandangan Alkitab muncul pada sejumlah surat kabar sains penciptaan yang berhubungan dengan [[Creation Research Society]]. Umumnya menunjuk kepada beberapa nas [[Alkitab]], yang secara harfiah mengindikasikan pergerakan harian Matahari dan Bulan yang dapat diamati mengelilingi Bumi, bukan karena rotasi Bumi pada aksisnya, misalnya pada {{Alkitab|Yosua 10:12}} di mana Matahari dan Bulan dikatakan berhenti di langit, dan {{Alkitab|Mazmur 93:1}} di mana dunia digambarkan tidak bergerak.<ref name= "Numbers1993">{{cite book|title= The Creationists: The Evolution of Scientific Creationism|publisher= University of California Press|last= Numbers|first= Ronald L.|authorlink= Ronald L. Numbers|year= 1993|page= 237|isbn= 0520083938}}</ref> Para pendukung kontemporer kepercayaan agamawi itu termasuk [[Robert Sungenis]] (presiden dari[[Bellarmine Theological Forum]] dan pengarang buku terbitan tahun 2006 ''Galileo Was Wrong'' (Galileo keliru)).<ref name= "Sefton2006">{{cite news |url= http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=_1kaAAAAIBAJ&sjid=XCYEAAAAIBAJ&dq=robert-sungenis&pg=6714%2C4991566 |title= In this world view, the sun revolves around the earth |first= Dru |last= Sefton |newspaper= [[Times-News (Hendersonville, North Carolina)|Times-News]] |location= Hendersonville, NC |date= 2006-03-30 |page= 5A}}</ref> Orang-orang ini mengajarkan pandangan bahwa pembacaan langsung Alkitab memuat kisah akurat bagaimana alam semesta diciptakan dan membutuhkan pandangan geosentrik. Kebanyakan organisasi kreasionis kontemporer menolak pandangan ini.{{refn|group=n|Donald B. DeYoung, misalnya, menyatakan bahwa "Similar terminology is often used today when we speak of the sun's rising and setting, even though the earth, not the sun, is doing the moving. Bible writers used the 'language of appearance,' just as people always have. Without it, the intended message would be awkward at best and probably not understood clearly. When the Bible touches on scientific subjects, it is entirely accurate."<ref>{{cite web |last= DeYoung |first= Donald B. |date= 1997-11-05 |title= Astronomy and the Bible: Selected questions and answers excerpted from the book |url=http://www.answersingenesis.org/Docs/399.asp |accessdate= 2013-12-01 |publisher= Answers in Genesis}}</ref>}} |

||

{{quote|Dari semuanya, Kopernikanisme merupakan kemenangan besar pertama sains atas agama, sehingga tidak dapat dihindari bahwa sejumlah orang berpikir semua yang salah dengan dunia ini bermula dari sana. (Steven Dutch dari [[University of Wisconsin–Madison]]) <ref>[http://www.uwgb.edu/dutchs/PSEUDOSC/Geocentrism.HTM Geocentrism lives]</ref>}} |

{{quote|Dari semuanya, Kopernikanisme merupakan kemenangan besar pertama sains atas agama, sehingga tidak dapat dihindari bahwa sejumlah orang berpikir semua yang salah dengan dunia ini bermula dari sana. (Steven Dutch dari [[University of Wisconsin–Madison]]) <ref>[http://www.uwgb.edu/dutchs/PSEUDOSC/Geocentrism.HTM Geocentrism lives]</ref>}} |

||

[[Morris Berman]] mengutip bahwa hasil survei menyatakan saat ini sekitar 20% penduduk Amerika Serikat percaya bahwa matahari mengitari bumi (geosentrisme) bukan bumi mengitari matahari (heliosentrisme), sementara 9% mengatakan tidak tahu.<ref name="Berman2006">{{cite book |

[[Morris Berman]] mengutip bahwa hasil survei menyatakan saat ini sekitar 20% penduduk Amerika Serikat percaya bahwa matahari mengitari bumi (geosentrisme) bukan bumi mengitari matahari (heliosentrisme), sementara 9% mengatakan tidak tahu.<ref name="Berman2006">{{cite book|last= Berman|first= Morris|authorlink= Morris Berman|title= Dark Ages America: The Final Phase of Empire|year= 2006|publisher= W.W. Norton & Company|isbn= 9780393058666}}</ref> Beberapa poll yang dilakukan oleh [[The Gallup Organization|Gallup]] pada tahun 1990-an mendapati bahwa 16% orang Jermans, 18% orang Amerika dan 19% orang Inggris/Britania Raya percaya bahwa Matahari mengitari Bumi.<ref name= "Crabtree1999">{{cite web |url= http://www.gallup.com/poll/3742/new-poll-gauges-americans-general-knowledge-levels.aspx |title= New Poll Gauges Americans' General Knowledge Levels |first= Steve |last= Crabtree |publisher= [[The Gallup Organization|Gallup]] |date= 1999-07-06}}</ref> Suatu studi yang dilakukan pada tahun 2005 oleh Jon D. Miller dari [[Northwestern University]], seorang pakar pemahaman publik akan sains dan teknologi,<ref name= "MillerBio">{{cite web |url= http://www.cmb.northwestern.edu/faculty/jon_miller.htm |title= Jon D. Miller |work= Northwestern University website |accessdate= 2007-07-19}}</ref> mendapati sekitar 20%, atau seperlima, orang dewasa Amerika percaya bahwa Matahari mengitari Bumi.<ref name= "Dean2005">{{cite news |url= http://www.nytimes.com/2005/08/30/science/30profile.html?ex=1184990400&en=2fb126c3132f89ae&ei=5070 |title=Scientific savvy? In U.S., not much |first= Cornelia |last= Dean |date= 2005-08-30 |newspaper= New York Times |accessdate= 2007-07-19}}</ref> Menurut poll tahun 2011 oleh [[VTSIOM]], 32% orang [[Russia]] percaya bahwa Matahari mengitari Bumi.<ref name= "RussianStudy2011">{{citation |url= http://wciom.ru/index.php?id=459&uid=111345 |title= 'СОЛНЦЕ - СПУТНИК ЗЕМЛИ', ИЛИ РЕЙТИНГ НАУЧНЫХ ЗАБЛУЖДЕНИЙ РОССИЯН |trans_title= 'Sun-earth', or rating scientific fallacies of Russians |issue= Пресс-выпуск №1684 <nowiki>[</nowiki>Press release no. 1684<nowiki>]</nowiki> |date= 2011-02-08 |language= ru |publisher= ВЦИОМ <nowiki>[</nowiki>[[VTSIOM|All-Russian Center for the Study of Public Opinion]]<nowiki>]</nowiki> |postscript= .}}</ref> |

||

[[Albert Einstein]] berpendapat: |

[[Albert Einstein]] berpendapat: |

||

| Baris 161: | Baris 161: | ||

== Referensi == |

== Referensi == |

||

{{reflist|colwidth=30em|refs= |

{{reflist|colwidth=30em|refs= |

||

<ref name= "Lawson2004">{{cite book |

<ref name= "Lawson2004">{{cite book|last= Lawson|first= Russell M.|year= 2004|title= Science in the Ancient World: An Encyclopedia |pages= [http://books.google.com/?id=1AY1ALzh9V0C&pg=PA30 29–30] |

||

|publisher= [[ABC-CLIO]] |

|publisher= [[ABC-CLIO]]|isbn= 1851095349|ref={{Harvid|Lawson|2004}}}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "Fraser2006">{{cite book |

<ref name= "Fraser2006">{{cite book|last= Fraser|first= Craig G.|title= The Cosmos: A Historical Perspective|year= 2006|page= 14}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "Goldstein1967">{{cite journal |

<ref name= "Goldstein1967">{{cite journal|title= The Arabic version of Ptolemy's planetary hypothesis|first= Bernard R.|last= Goldstein|page= 6|journal= Transactions of the American Philosophical Society|year= 1967|volume= 57|issue= pt. 4|jstor= 1006040}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "Goldstein1972">{{cite journal |

<ref name= "Goldstein1972">{{cite journal|first= Bernard R.|last= Goldstein|year= 1972|title= Theory and observation in medieval astronomy|journal= Isis|volume= 63|issue= 1|page= 41}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "Setia2004">{{Cite journal |

<ref name= "Setia2004">{{Cite journal|title= Fakhr Al-Din Al-Razi on physics and the nature of the physical world: A preliminary survey|first= Adi|last= Setia|journal= Islam & Science|volume= 2|year= 2004}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "JohansenRosenmeier1998">{{cite book |

<ref name= "JohansenRosenmeier1998">{{cite book|first1= K. F.|last1=Johansen|first2= H.|last2= Rosenmeier|title= A History of Ancient Philosophy: From the Beginnings to Augustine|year= 1998|page= 43}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "Sarton1953">{{cite book |

<ref name= "Sarton1953">{{cite book|first= George|last= Sarton|title= Ancient Science Through the Golden Age of Greece|year= 1953|page= 290}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "Eastwood1992">{{Cite journal |

<ref name= "Eastwood1992">{{Cite journal|volume= 23|page= 233|last= Eastwood|first= B. S.|title= Heraclides and heliocentrism – Texts diagrams and interpretations|journal= Journal for the History of Astronomy|date= 1992-11-01}}</ref> |

||

<ref name="Lindberg2010">{{cite book |

<ref name="Lindberg2010">{{cite book|last= Lindberg|first= David C.|title= The Beginnings of Western Science: The European Scientific Tradition in Philosophical, Religious, and Institutional Context, Prehistory to A.D. 1450|edition= 2nd|year= 2010|publisher= University of Chicago Press|isbn= 9780226482040|page= [http://books.google.com/books?id=dPUBAkIm2lUC&pg=PA197 197]}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "Russell1945">{{cite book |

<ref name= "Russell1945">{{cite book|last= Russell|first= Bertrand|authorlink= Bertrand Russell|title= [[A History of Western Philosophy]]|origyear= 1945|year= 2013|publisher= Routledge|page= 215|isbn= 9781134343676}}</ref> |

||

<ref name="Nussbaum2007">{{Cite journal |

<ref name="Nussbaum2007">{{Cite journal|url= http://www.skeptic.com/the_magazine/featured_articles/v12n03_orthodox_judaism_and_evolution.html|title= Orthodox Jews & science: An empirical study of their attitudes toward evolution, the fossil record, and modern geology|accessdate= 2008-12-18|last= Nussbaum|first= Alexander|date= 2007-12-19|journal= Skeptic Magazine}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "Nussbaum2002">{{cite journal |

<ref name= "Nussbaum2002">{{cite journal|first= Alexander|last= Nussbaum|title= Creationism and geocentrism among Orthodox Jewish scientists|journal= Reports of the National Center for Science Education|date=January–April 2002|pages= 38–43}}</ref> |

||

<ref name="SchneersohnGotfryd2003">{{cite book |

<ref name="SchneersohnGotfryd2003">{{cite book|last1= Schneersohn|first1= Menachem Mendel|authorlink1= Menachem Mendel Schneerson|last2= Gotfryd|first2= Arnie|title= Mind over Matter: The Lubavitcher Rebbe on Science, Technology and Medicine|pages= [http://books.google.com/books?id=FmabnhsgSVAC&pg=PA76 76ff.]; cf. xvi-xvii, [http://books.google.com/books?id=FmabnhsgSVAC&pg=PA69 69], [http://books.google.com/books?id=FmabnhsgSVAC&pg=PA100 100–1], [http://books.google.com/books?id=FmabnhsgSVAC&pg=PA171 171–2], [http://books.google.com/books?id=FmabnhsgSVAC&pg=PA408 408ff.]|year= 2003|publisher= Shamir|isbn= 9789652930804}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "Mishneh Torah">{{cite book |

<ref name= "Mishneh Torah">{{cite book|title= Mishneh Torah|url= http://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/947929/jewish/Chapter-Eleven.htm|chapter= Sefer Zemanim: Kiddush HaChodesh: Chapter 11|page= Halacha 13–14|nopp=y|others= Translated by Touger, Eliyahu|publisher= Chabad-Lubavitch Media Center}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "Rabinowitz1987">{{cite web |

<ref name= "Rabinowitz1987">{{cite web|url= http://www.pages.nyu.edu/%7Eair1/GeoCentrism%20&%20EgoCentrism,%20Existentialist%20Despair%20&%20Significance.htm|first= Avi|last= Rabinowitz|year= 1987|title= EgoCentrism and GeoCentrism; Human Significance and Existential Despair; Bible and Science; Fundamentalism and Skepticalism|work= Science & Religion|accessdate=2013-12-01}} Published in {{cite book|editor1-last= Branover|editor1-first= Herman|editor2-last=Attia|editor2-first= Ilana Coven|title= Science in the Light of Torah: A B'Or Ha'Torah Reader|year= 1994|publisher= Jason Aronson|isbn=9781568210346}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "Hort1822">{{cite book |

<ref name= "Hort1822">{{cite book|first= William Jillard|last= Hort|title= A General View of the Sciences and Arts|year= 1822|page= 182}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "Kaler2002">{{cite book |

<ref name= "Kaler2002">{{cite book|last= Kaler|first= James B.|title= The Ever-changing Sky: A Guide to the Celestial Sphere|year= 2002|page= 25}}</ref> |

||

}} |

}} |

||

== Pustaka == |

== Pustaka == |

||

* {{cite book |

* {{cite book|title = Theories of the World from Antiquity to the Copernican Revolution|last = Crowe|first= Michael J.|publisher = Dover Publications|year = 1990|location = Mineola, NY|isbn = 0486261735|ref = {{Harvid|Crowe|1990}}}} |

||

*{{cite book |

*{{cite book|title= A History of Astronomy from Thales to Kepler|last= Dreyer|first= J.L.E.|publisher= Dover Publications|year= 1953|url=http://www.archive.org/details/historyofplaneta00dreyuoft|location= New York |

||

|ref={{Harvid|Dreyer|1953}}|authorlink= John Louis Emil Dreyer}} |

|||

*{{cite book |

*{{cite book|last= Evans|first= James|title= The History and Practice of Ancient Astronomy|location= New York|publisher= Oxford University Press|year= 1998|ref={{Harvid|Evans|1998}}}} |

||

*{{cite book |

*{{cite book|last= Heath|first= Thomas|authorlink= T. L. Heath|title= Aristarchus of Samos|location= Oxford|publisher= Clarendon Press|year= 1913|ref={{Harvid|Heath|1913}}}} |

||

*{{cite book |

*{{cite book|authorlink= Sir Fred Hoyle|last= Hoyle|first= Fred|title= Nicolaus Copernicus|year= 1973|ref={{Harvid|Hoyle|1973}}}} |

||

*{{cite book |

*{{cite book|authorlink= Arthur Koestler|last= Koestler|first= Arthur|title= The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe|origyear= 1959|publisher= Penguin Books|year= 1986|isbn= 014055212X|ref={{Harvid|Koestler|1959}}}} 1990 reprint: ISBN 0140192468. |

||

*{{cite book |

*{{cite book|authorlink= Thomas Samuel Kuhn|last= Kuhn|first= Thomas S.|title= The Copernican Revolution|location= Cambridge|publisher= Harvard University Press|year= 1957|isbn= 0674171039|ref={{Harvid|Kuhn|1957}}}} |

||

*{{cite book |

*{{cite book|title= From Eudoxus to Einstein—A History of Mathematical Astronomy|last= Linton|first= Christopher M.|publisher= Cambridge University Press|year= 2004|location= Cambridge|isbn= 9780521827508|ref={{Harvid|Linton|2004}}}} |

||

*{{cite book |

*{{cite book|editor-last= Walker|editor-first= Christopher|title= Astronomy Before the Telescope|location= London|publisher= British Museum Press|year= 1996|isbn= 0714117463|ref={{Harvid|Walker|1996}}}} |

||

== Pranala luar == |

== Pranala luar == |

||

Revisi per 15 Maret 2016 21.09

Geosentrisme atau disebut Teori Geosentrik, Model Geosentrik (bahasa Inggris: geocentric model atau geocentrism, Ptolemaic system) adalah istilah astronomi yang menggambarkan alam semesta dengan bumi sebagai pusatnya dan pusat pergerakan semua benda-benda langit. Model ini menjadi sistem kosmologi predominan pada budaya kuno misalnya Yunani kuno, yang meliputi sistem-sistem terkenal yang dikemukakan oleh Aristoteles and Claudius Ptolemaeus.[1]

Dua pengamatan umum mendukung pandangan bahwa Bumi adalah pusat dari alam semesta. Pengamatan pertama adalah bintang-bintang, matahari dan planet-planet nampak berputar mengitari bumi setiap hari, membuat bumi adalah pusat sistem ini. Lebih lanjut, setiap bintang berada pada suatu bulatan stelar atau selestial ("stellar sphere" atau "celestial sphere"), di mana bumi adalah pusatnya, yang berkeliling setiap hari, di seputar garis yang menghubungkan kutub utara dan selatan sebagai aksisnya. Bintang-bintang yang terdekat dengan khatulistiwa nampak naik dan turun paling jauh, tetapi setiap bintang kembali ke titik terbitnya setiap hari.[2] Observasi umum kedua yang mendukung model geosentrik adalah bumi nampaknya tidak bergerak dari sudut pandang pengamat yang berada di bumi, bahwa bumi itu solid, stabil dan tetap di tempat. Dengan kata lain, benar-benar dalam posisi diam.

Model geosentrik biasanya dikombinasi dengan suatu Bumi yang bulat oleh filsuf Romawi kuno dan abad pertengahan. Ini tidak sama dengan pandangan model Bumi datar yang disiratkan dalam sejumlah mitologi, sebagaimana juga dalah kosmologi kitab-kitab suci dan Latin kuno.[n 1][n 2][n 3]

Yunani kuno

Teori atau model Geosentrik memasuki astronomi dan filsafat Yunani sejak dini; dapat ditelusuri pada peninggalan filsafat sebelum zaman Sokrates. Pada abad ke-6 SM, Anaximander mengemukakan suatu kosmologi dengan bumi berbentuk seperti potongan suatu tiang (sebuah tabung), berada di awang-awang di pusat segala sesuatu. Matahari, Bulan, and planet-planet adalah lubang-lubang dalam roda-roda yang tidak kelihatan yang mengelilingi bumi; melalui lubang-lubang ini manusia dapat melihat api yang tersembunyi. Pada waktu yang sama, para pengikut Pythagoras, yang disebut kelompok Pythagorean, berpendapat bahwa bumi adalah suatu bola (menurut pengamatan gerhana-gerhana), tetapi bukan sebagai pusat, melainkan bergerak mengelilingi suatu api yang tidak nampak. Kemudian pandangan-pandangan ini digabungkan, sehingga kalangan terpelajar Yunani sejak dari abad ke-4 SM berpikir bahwa bumi adalah bola yang menjadi pusat alam semesta.[6]

Model Ptolemaik

Meskipun prinsip dasar geosentrisme Yunani sudah tersusun pada zaman Aristoteles, detail sistem ini belum menjadi standar. Sistem Ptolemaik, yang diutarakan oleh astronomer Helenistik Mesir Claudius Ptolemaeus pada abad ke- 2 M akhirnya berhasil menjadi standar. Karya astronomi utamanya, Almagest, merupakan puncak karya-karya selama berabad-abad-abad oleh para astronom Yunani kuno, Helenistik dan Babilonia; karya itu diterima selama lebih dari satu milenium sebagai model kosmologi yang benar oleh para astronom Eropa dan Islam. Karena begitu kuat pengaruhnya, sistem Ptolemaik kadang kala dianggap sama dengan model geosentrik.

Ptolemy berpendapat bahwa bumi adalah pusat alam semesta berdasarkan pengamatan sederhana yaitu setengah jumlah bintang-bintang terletak di atas horizon dan setengahnya di bawah horizon pada waktu manapun (bintang-bintang pada bulatan orbitnya), dan anggapan bahwa bintang–bintang semuanya terletak pada suatu jarak tertentu dari pusat semesta. Jika bumi terletak cukup jauh dari pusat semesta, maka pembagian bintang-bintang yang tampak dan tidak tampak tidaklah akan sama. l.[n 4]

Sistem Ptolemaik

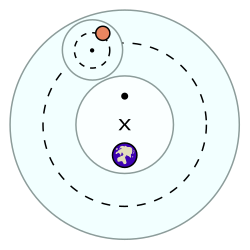

Dalam Sistem Ptolemaik, setiap planet digerakkan oleh suatu sistem yang memuat dua bola atau lebih: satu disebut "deferent" yang lain "epicycle" .

Sekalipun model geosentrik digantikan oleh model heliosentrik. Namun, model deferent dan epicycle tetap dipakai karena menghasilkan prediksi yang akurat dan lebih sesuai dengan pengamatan dibanding sistem-sistem lain. Epicycle Venus dan Mercurius selalu berpusat pada suatu garis antara Bumi dan Matahari (Merkurius lebih dekat ke Bumi), yang menjelaskan mengapa kedua planet itu selalu dekat di langit. Model ini digantikan oleh model eliptik Kepler hanya ketika metode pengamatan (yang dikembangkan oleh Tycho Brahe dan lain-lain) menjadi cukup akurat untuk meragukan model epicycle.

Urutan lingkaran-lingkaran orbit dari bumi ke luar adalah:[8]

- Bulan

- Merkurius

- Venus

- Matahari

- Mars

- Yupiter

- Saturnus

- Bintang-bintang tetap

- Primum Mobile ("Yang pertama bergerak").

Urutan ini tidak diciptakan atau merupakan hasil karya Ptolemaeus, melainkan diselaraskan dengan kosmologi agamawi "Tujuh Langit" yang umum ditemui pada tradisi agamawi Eurasia utama.

Geosentrisme dan Astronomi Islam

Dikarenakan dominansi ilmiah sistem Ptolemaik dalam astronomi Islam, para astronom Muslim menerima bulat model geosentrik.[n 5]

Pada abad ke-12, Arzachel meninggalkan ide Yunani kuno "pergerakan melingkar uniform" (uniform circular motion) dengan membuat hipotesis bahwa planet Merkurius bergerak dalam orbit eliptik,[10][11] sedangkan Alpetragius mengusulkan model planetari yang meninggalkan equant, mekanisme epicycle dan eksentrik,[12] meskipun ini menghasilkan suatu sistem yang lebih kurang akurat secara matematik.[13] Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (1149–1209), sehubungan dengan konsepsi fisika dan dunia fisika dalam karyanya Matalib, menolak pandangan Aristotelian dan Avicennian bahwa Bumi berada di pusat alam semesta, melainkan berpendapat bahwa ada "ribuan-ribuan dunia (alfa alfi 'awalim) di luar dunia ini sedemikian sehingga setiap dunia ini lebih besar dan masif dari dunia ini serta serupa dengan dunia ini." Untuk mendukung argumen teologinya, ia mengutip dari Al Quran, "All praise belongs to God, Lord of the Worlds," menekankan istilah "Worlds" (dunia-dunia).[14]

Geosentrisme dan sistem-sistem saingan

Tidak semua orang Yunani setuju dengan model geosentrik. Sistem Pythagorean yang sudah disinggung sebelumnya meyakini bahwa Bumi merupakan salah satu dari beberapa planet yang bergerak mengelilingi suatu api di tengah-tengah.[15] Hicetas dan Ecphantus, dua penganut Pythagorean dari abad ke-5 SM, dan Heraclides Ponticus dari abad ke-4 SM, percaya bahwa Bumi berputra mengelilingi aksisnya, tetapi tetap berada di tengah alam semesta.[16] Sistem semacam itu masih tergolong geosentrik. Pandangan ini dibangkitkan kembali pada Abad Pertengahan oleh Jean Buridan. Heraclides Ponticus suatu ketika dianggap berpandangan bahwa baik Venus maupun Merkurius mengelilingi Matahari, bukan Bumi, tetapi anggapan ini tidak lagi diterima.[17] Martianus Capella secara definitif menempatkan Merkurius dan Venus pada suatu orbit mengitari Matahari.[18] Aristarchus dari Samos adalah yang paling radikal, dengan menulis dalam karyanya (yang tidak lagi terlestarikan) mengenai heliosentrisme, bahwa Matahari adalah pusat alam semesta, sedangkan Bumi dan planet-planet lain mengitarinya.[19] Teorinya tidak populer pada masanya, dan ia mempunyai satu pengikut yang bernama, Seleucus of Seleucia.[20]

Sistem Kopernikan

Dengan penemuan teleskop pada tahun 1609, pengamatan yang dilakukan oleh Galileo Galilei (antara lain bahwa Yupiter memiliki sejumlah bulan) mempertanyakan sejumlah prinsip geosentrisme tetapi tidak secara serius mengancamnya. Karena ia mengamati adanya "titik-titik" gelap pada Bulan, kawah-kawah, ia berkomentar bahwa Bulan bukanlah benda langit sempurna sebagaimana anggapan sebelumnya. Ini pertama kalinya orang dapat melihat cacat pada suatu benda langit yang dianggap terbuat dari aether yang sempurna. Sedemikian, karena cacatnya bulan sekarang dapat dikaitkan dengan apa yang dilihat di Bumi, orang dapat berargumen bahwa keduanya tidak unik, melainkan terbuat dari bahan yang serupa. Galileo juga dapat melihat bulan-bulan yang mengitari Yupiter, yang didedikasikannya kepada Cosimo II de' Medici, dan menyatakan bahwa bulan-bulan itu mengorbit Yupiter, bukan Bumi.[21] Ini merupakan klaim signifikan karena jika benar, berarti tidak semua benda langit mengitari Bumi, menghancurkan kepercayaan teologi dan ilmiah yang dianut sebelumnya. Namun, teori-teori Galileo yang menantang geosentrisme alam semesta dibungkam oleh pihak gereja dan sikap skeptik umum terhadap sistem yang tidak menempatkan Bumi di pusat semesta, mempertahankan pikiran dan sistem Ptolemaeus dan Aristoteles.

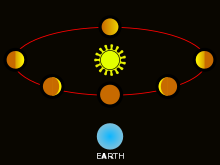

Pada bulan Desember 1610, Galileo Galilei menggunakan teleskopnya untuk mengamati semua fase planet Venus, sebagaimana fase-fase Bulan. Ia berpikir bahwa pengamatan ini tidak kompatibel dengan sistem Ptolemaik, tetapi merupakan konsekwensi alamiah dari sistem heliosentrik system.

Ptolemaeus menempatkan deferent dan epicycle Venus seluruhnya di dalam bulatan Matahari (antara Matahari dan Merkurius), tetapi ini hanya sekadar penempatan; dapat saja tempat Venus dan Merkurius ditukar, selama mereka selalu berada pada satu garis yang menghubungkan Bumi ke Matahari, seperti penempatan pusat epicycle Venus dekat dengan Matahari. Dalam kasus ini, jika Matahari menjadi sumber semua cahaya, di bawah sistem Ptolemaik:

Jika Venus berada di antara Bumi dan Matahari, fase Venus seharusnya selalu berbentuk sabit atau seluruhnya gelap. Jika Venus berada di balik Matahari, fase Venus seharusnya selalu hampir penuh (gibbous) atau purnama.

Namun Galileo melihat Venus mulanya kecil dan purnama, kemudian besar dan bayangannya berbentuk sabit.

Ini menunjukkan bahwa dengan kosmologi Ptolemaik, epicycle Venus tidak dapat sepenuhnya di dalam maupun di luar orbit matahari. Akibatnya, pada sistem Ptolemaik pandangan bahwa epicycle Venus sepenuhnya di dalam matahari ditinggalkan, dan kemudian pada abad ke-17 kompetisi antara kosmologi astronomi berfokus pada variasi sistem Tychonik yang dikemukakan oleh Tycho Brahe, di mana Bumi masih menjadi pusat alam semesta, dikitari oleh matahari, tetapi semua planet lain berputar mengelilingi matahari sebagi suatu himpunan epicycle masif), atau variasi-variasi Sistem Kopernikan.

Gravitasi

Johannes Kepler,setelah menganalisa pengamatan akurat Tycho Brahe, menyusun ketiga hukum gerakan planetarinya (Hukum Gerakan Planet Kepler (Kepler's laws of planetary motion) pada tahun 1609 dan 1619, berdasarkan pandangan heliosentrik dimana gerakan planet-planet dalam jalur eliptik. Menggunakan hukum-hukum ini, Kepler merupakan astronom pertama yang dengan sukses meramalkan pergerakan planet Venus (untuk tahun 1631). Transisi dari orbit lingkaran ke jalur planetari eliptik secara dramatis mengubah keakuratan pengamatan dan peramalan selestial. Karena model heliosentrik Copernicus tidak lebih akurat dari sistem Ptolemaeus, pengamatan-pengamatan matematik diperlukan untuk meyakinkan mereka yang masih berpegang pada model geosentrik. Namun, pengamatan yang dibuat oleh Kepler, menggunakan data dari Brahe, menjadi problem yang tidak mudah dipecahkan oleh para penganut geosentrisme.

Pada tahun 1838, astronom Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel dengan sukses mengukur paralaks bintang 61 Cygni, membuktikan bahwa Ptolemaeus keliru dalam berpendapat bahwa gerakan paralaks tidak ada. Ini akhirnya menguatkan pernyataan Copernicus dengan pengamatan ilmiah yang akurat dan dapat diandalkan, serta menunjukkan betapa jauhnya bintang-bintang dari bumi.

Kerangka geosentrik berguna untuk aktivitas sehari-hari dan kebanyakan eksperimen laboratorium, namun kurang cocok untuk mekanika tata surya dan perjalanan di ruang angkasa. Meskipun kerangka heliosentrik berguna untuk hal-hal tersebut, astronomi galaksi maupun di luar galaksi menjadi lebih mudah jika matahari dianggap tidak diam atau pun menjadi pusat alam semesta, melainkan berputar mengelilingi pusat galaksi kita, dan galaksi kita selanjutnya juga tidak diam dalam hubungan dengan latar belakang kosmik.

Penganut geosentrisme agamawi dan kontemporari

Model Ptolemaik mengenai tata surya masih terus dianut sampai ke awal zaman modern. Sejak akhir abad ke-16 dan seterusnya perlahan-lahan digantikan sebagai penggambaran konsensus oleh model heliosentrisme. Geosentrisme sebagai suatu kepercayaan agamawi terpisah, tidak pernah padam. Di Amerika Serikat antara tahun 1870-1920, misalnya, berbagai anggota Gereja Lutheran – Sinode Missouri menerbitkan artikel-artikel yang menyerang sistem astronomi Kopernikan, dan geosentrisme banyak diajarkan di dalam sinode dalam periode tersebut.[22] Namun, pada tahun 1902 Theological Quarterly, A. L. Graebner menyatakan bahwa sinode itu tidak mempunyai posisi doktrinal terhadap geosentrisme, heliosentrisme, atau model ilmiah lainnya, kecuali kalau itu bertolak belakang dengan Alkitab. Ia menyatakan pula bahwa deklarasi apapun yang dikemukakan para penganut geosentrisme di dalam sinode bukan merupakan pendapat badan gereja secara keseluruhan.[23]

Artikel-artikel yang mendukung geosentrisme sebagai pandangan Alkitab muncul pada sejumlah surat kabar sains penciptaan yang berhubungan dengan Creation Research Society. Umumnya menunjuk kepada beberapa nas Alkitab, yang secara harfiah mengindikasikan pergerakan harian Matahari dan Bulan yang dapat diamati mengelilingi Bumi, bukan karena rotasi Bumi pada aksisnya, misalnya pada Yosua 10:12 di mana Matahari dan Bulan dikatakan berhenti di langit, dan Mazmur 93:1 di mana dunia digambarkan tidak bergerak.[24] Para pendukung kontemporer kepercayaan agamawi itu termasuk Robert Sungenis (presiden dariBellarmine Theological Forum dan pengarang buku terbitan tahun 2006 Galileo Was Wrong (Galileo keliru)).[25] Orang-orang ini mengajarkan pandangan bahwa pembacaan langsung Alkitab memuat kisah akurat bagaimana alam semesta diciptakan dan membutuhkan pandangan geosentrik. Kebanyakan organisasi kreasionis kontemporer menolak pandangan ini.[n 6]

Dari semuanya, Kopernikanisme merupakan kemenangan besar pertama sains atas agama, sehingga tidak dapat dihindari bahwa sejumlah orang berpikir semua yang salah dengan dunia ini bermula dari sana. (Steven Dutch dari University of Wisconsin–Madison) [27]

Morris Berman mengutip bahwa hasil survei menyatakan saat ini sekitar 20% penduduk Amerika Serikat percaya bahwa matahari mengitari bumi (geosentrisme) bukan bumi mengitari matahari (heliosentrisme), sementara 9% mengatakan tidak tahu.[28] Beberapa poll yang dilakukan oleh Gallup pada tahun 1990-an mendapati bahwa 16% orang Jermans, 18% orang Amerika dan 19% orang Inggris/Britania Raya percaya bahwa Matahari mengitari Bumi.[29] Suatu studi yang dilakukan pada tahun 2005 oleh Jon D. Miller dari Northwestern University, seorang pakar pemahaman publik akan sains dan teknologi,[30] mendapati sekitar 20%, atau seperlima, orang dewasa Amerika percaya bahwa Matahari mengitari Bumi.[31] Menurut poll tahun 2011 oleh VTSIOM, 32% orang Russia percaya bahwa Matahari mengitari Bumi.[32]

Albert Einstein berpendapat:

- Pergulatan, begitu keras di awal masa sains, antara pandangan Ptolemaeus dan Kopernikus, sebenarnya tidak berarti. Kedua sistem koordinat ini dapat digunakan dengan justifikasi setara. Kedua kalimat: "matahari diam dan bumi bergerak", atau "matahari bergerak dan bumi diam", hanya bermakna konvensi yang berbeda dari dua sistem koordinat yang berbeda.[33]

Stephen Hawking, dalam bukunya "The Grand Design", menyatakan pandangan yang tepat sama dengan Einstein:

- Maka apakah yang sesungguhnya, sistem Ptolemaik atau Kopernikan? Meskipun tidak jarang orang mengatakan Kopernikus membuktikan Ptolemaeus salah, hal ini tidak benar.[34]

Posisi historis hierarki Katolik Roma

Galileo affair yang terkenal menghadapkan model geosentrik dengan pernyataan Galileo. Mengenai basis teologi dari argumen semacam itu, dua orang Paus membahas pertanyaan apakah penggunaan bahasa fenomenologi (berdasarkan pengamatan) akan memaksa orang mengakui kesalahan Alkitab. Keduanya mengajarkan bahwa tidak demikian halnya.

Yudaisme Ortodoks

Sejumlah pemimpin Yudaisme Ortodoks, terutama Lubavitcher Rebbe, mempertahankan model geosentrik alam semesta berdasarkan ayat-ayat Alkitab dan penafsiran Maimonides sehingga ia mengajarkan bahwa bumi dikitari oleh matahari.[35][36] Lubavitcher Rebbe juga menjelaskan bahwa geosentrisme dapat dipertahankan berdasarkan teori Relativitas, dimana dinyatakan bahwa "ketika dua benda di udara bergerak relatif satu sama lain, ... ilmu alam mendeklarasikan dengan kepastian absolut bahwa dari segi sudut pandang ilmiah kedua kemungkinan itu valid, yaitu bumi mengitari matahari, atau matahari mengitari bumi."[37]

Meskipun geosentrisme penting untuk perhitungan kalender Maimonides,[38] mayoritas sarjana agamawi Yahudi, yang menerima keilahian Alkitab dan menerima banyak aturan-aturannya mengikat secara hukum, tidak percaya bahwa Alkitab maupun Maimonides memerintahkan untuk percaya pada geosentrisme.[36][39] Namun, ada bukti bahwa kepercayaan geosentrisme meningkat di antara umat Yahudi Ortodoks.[35][36]

Islam

Kasus-kasus prominent geosentrisme modern dalam Islam sangat terisolasi. Hanya sedikit individu yang mengajarkan suatu pandangan geosentrik alam semesta. Salah satunya adalah Grand Mufti Saudi Arabia tahun 1993-1999, Abd al-Aziz ibn Abd Allah ibn Baaz (Ibn Baz), yang mengajarkan pandangan ini antara tahun 1966-1985.

Planetarium

Model geosentrik (Ptolemaik) tata surya terus digunakan oleh para pembuat planetarium karena berdasarkan alasan teknis pergerakan tipe Ptolemaik untuk aparatus cahaya planet memiliki sejumlah kelebihan dibandingkan teori pergerakan Kopernikus.[40] Sistem bulatan selestial yang digunakan untuk tujuan pengajaran dan navigasi juga didasarkan pada sistem geosentrik[41] yang mengabaikan efek paralaks. Namun, efek ini dapat diabaikan pada skala akurasi yang diterapkan pada suatu planetarium.

Lihat pula

Catatan

- ^ Alam semesta Mesir secara isi sama dengan alam semesta Babel, yaitu digambarkan seperti kotak persegi panjang dengan orientasi utara-selatan dan dengn permukaan sedikit cembung, di mana Mesir adalah pusatnya. Pandangan astronomi Ibrani kuno yang serupa dapat dilihat dari tulisan-tulisan kitab suci, misalnya teori penciptaan semesta dan berbagai mazmur yang menyebut "cakrawala", bintang-bintang, matahari dan bumi. Orang Ibrani memandang bumi seakan-akan sebagai permukaan datar yang terdiri dari bagian padat dan cair, dan langit sebagai alam cahaya di mana benda-benda langit bergerak. Bumi ditopang oleh batu-batu penjuru dan tidak dapat digerakkan selain oleh Yahweh (misalnya dalam kaitan dengan gempa bumi). Menurut orang Ibrani, matahari dan bulan berjarak dekat satu sama lain[3]

- ^ Gambaran alam semesta dalam teks-teks Talmud adalah bumi di tengah ciptaan dengan langit sebagai bulatan yang dibentangkan di atasnya. Bumi biasanya digambarkan seperti sebuah piring yang dikelilingi oleh air. Yang menarik spekulasi kosmologi dan metafisika tidak ditanamkan dalam publik maupun dilestarikan dalam tulisan. Namun, dianggap lebih sebagai "rahasia-rahasia Taurat yang tidak seharusnya diturunkan semua orang dan kalangan" (Ketubot 112a). Meskipun studi penciptaan Allah tidak dilarang, spekulasi tentang "apa yang ada di atas, di bawah, yang ada sebelumnya dan yang kemudian" (Mishnah Hagigah: 2) dibatasi hanya untuk elite intelektual.[4]

- ^ Sebagaimana Midrash dan Talmud, Targum tidak berpandangan adanya suatu bulatan bumi, melainkan suatu piringan bumi datar, yang dikitari matahari dalam jalur setengah lingkaran yang ditempuh rata-rata dalam 12 jam.[5]

- ^ Argumen ini ditulis pada iBuku I, Bab 5, Almagest.[7]

- ^ "Semua astronom Islam dari Thabit ibn Qurra pada abad ke-9 sampai Ibn al-Shatir pada abad ke-14, dan semua filsuf alamiah dari al-Kindi sampai Averroes dan seterusnya, diketahui telah menerima ... gambaran dunia menurut budaya Yunani yang terdiri dari dua bulatan, di mana salah satunya, bulatan selestial ... secara bulat membungkus yang lain."[9]

- ^ Donald B. DeYoung, misalnya, menyatakan bahwa "Similar terminology is often used today when we speak of the sun's rising and setting, even though the earth, not the sun, is doing the moving. Bible writers used the 'language of appearance,' just as people always have. Without it, the intended message would be awkward at best and probably not understood clearly. When the Bible touches on scientific subjects, it is entirely accurate."[26]

Referensi

- ^ Lawson, Russell M. (2004). Science in the Ancient World: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. hlm. 29–30. ISBN 1851095349.

- ^ Kuhn 1957, hlm. 5-20.

- ^ Abetti, Giorgio (2012). "Cosmology". Encyclopedia Americana (edisi ke-Online). Grolier.

- ^ Tirosh-Samuelson, Hava (2003). "Topic Overview: Judaism". Dalam van Huyssteen, J. Wentzel Vrede. Encyclopedia of Science and Religion. 2. New York: Macmillan Reference USA. hlm. 477–83.

- ^ Gandz, Solomon (1953). "The distribution of land and sea on the Earth's surface according to Hebrew sources". Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research. 22: 23–53.

- ^ Fraser, Craig G. (2006). The Cosmos: A Historical Perspective. hlm. 14.

- ^ Crowe 1990, hlm. 60–2

- ^ Goldstein, Bernard R. (1967). "The Arabic version of Ptolemy's planetary hypothesis". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 57 (pt. 4): 6. JSTOR 1006040.

- ^ Sabra, A. I. (1998). "Configuring the universe: Aporetic, problem solving, and kinematic modeling as themes of Arabic astronomy". Perspectives on Science. 6 (3): 317–8.

- ^ Rufus, W. C. (May 1939). "The influence of Islamic astronomy in Europe and the far east". Popular Astronomy. 47 (5): 233–8.

- ^ Hartner, Willy (1955). "The Mercury horoscope of Marcantonio Michiel of Venice". Vistas in Astronomy. 1: 118–22.

- ^ Goldstein, Bernard R. (1972). "Theory and observation in medieval astronomy". Isis. 63 (1): 41.

- ^ "Ptolemaic Astronomy, Islamic Planetary Theory, and Copernicus's Debt to the Maragha School". Science and Its Times. Thomson Gale. 2006.

- ^ Setia, Adi (2004). "Fakhr Al-Din Al-Razi on physics and the nature of the physical world: A preliminary survey". Islam & Science. 2.

- ^ Johansen, K. F.; Rosenmeier, H. (1998). A History of Ancient Philosophy: From the Beginnings to Augustine. hlm. 43.

- ^ Sarton, George (1953). Ancient Science Through the Golden Age of Greece. hlm. 290.

- ^ Eastwood, B. S. (1992-11-01). "Heraclides and heliocentrism – Texts diagrams and interpretations". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 23: 233.

- ^ Lindberg, David C. (2010). The Beginnings of Western Science: The European Scientific Tradition in Philosophical, Religious, and Institutional Context, Prehistory to A.D. 1450 (edisi ke-2nd). University of Chicago Press. hlm. 197. ISBN 9780226482040.

- ^ Lawson 2004, hlm. 19

- ^ Russell, Bertrand (2013) [1945]. A History of Western Philosophy. Routledge. hlm. 215. ISBN 9781134343676.

- ^ Finocchiaro, Maurice A. (2008). The Essential Galileo. Indianapolis, IL: Hackett. hlm. 49.

- ^ Babinski, E. T., ed. (1995). "Excerpts from Frank Zindler's 'Report from the center of the universe' and 'Turtles all the way down'". Cretinism of Evilution. TalkOrigins Archive (2). Diakses tanggal 2013-12-01.

- ^ Graebner, A. L. (1902). "Science and the church". Theological Quarterly. St. Louis, MO: Lutheran Synod of Missouri, Ohio and other states, Concordia Publishing. 6: 37–45.

- ^ Numbers, Ronald L. (1993). The Creationists: The Evolution of Scientific Creationism. University of California Press. hlm. 237. ISBN 0520083938.

- ^ Sefton, Dru (2006-03-30). "In this world view, the sun revolves around the earth". Times-News. Hendersonville, NC. hlm. 5A.

- ^ DeYoung, Donald B. (1997-11-05). "Astronomy and the Bible: Selected questions and answers excerpted from the book". Answers in Genesis. Diakses tanggal 2013-12-01.

- ^ Geocentrism lives

- ^ Berman, Morris (2006). Dark Ages America: The Final Phase of Empire. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393058666.

- ^ Crabtree, Steve (1999-07-06). "New Poll Gauges Americans' General Knowledge Levels". Gallup.

- ^ "Jon D. Miller". Northwestern University website. Diakses tanggal 2007-07-19.

- ^ Dean, Cornelia (2005-08-30). "Scientific savvy? In U.S., not much". New York Times. Diakses tanggal 2007-07-19.

- ^ 'СОЛНЦЕ - СПУТНИК ЗЕМЛИ', ИЛИ РЕЙТИНГ НАУЧНЫХ ЗАБЛУЖДЕНИЙ РОССИЯН (dalam bahasa Rusia) (Пресс-выпуск №1684 [Press release no. 1684]), ВЦИОМ [All-Russian Center for the Study of Public Opinion], 2011-02-08.

- ^ Albert Einstein. "The Evolution of Physics: From Early Concepts to Relativity and Quanta", halaman 212

- ^ Stephen Hawking. "The Grand Design", halaman 41.

- ^ a b Nussbaum, Alexander (2007-12-19). "Orthodox Jews & science: An empirical study of their attitudes toward evolution, the fossil record, and modern geology". Skeptic Magazine. Diakses tanggal 2008-12-18.

- ^ a b c Nussbaum, Alexander (January–April 2002). "Creationism and geocentrism among Orthodox Jewish scientists". Reports of the National Center for Science Education: 38–43.

- ^ Schneersohn, Menachem Mendel; Gotfryd, Arnie (2003). Mind over Matter: The Lubavitcher Rebbe on Science, Technology and Medicine. Shamir. hlm. 76ff.; cf. xvi-xvii, 69, 100–1, 171–2, 408ff. ISBN 9789652930804.

- ^ "Sefer Zemanim: Kiddush HaChodesh: Chapter 11". Mishneh Torah. Translated by Touger, Eliyahu. Chabad-Lubavitch Media Center. Halacha 13–14.

- ^ Rabinowitz, Avi (1987). "EgoCentrism and GeoCentrism; Human Significance and Existential Despair; Bible and Science; Fundamentalism and Skepticalism". Science & Religion. Diakses tanggal 2013-12-01. Published in Branover, Herman; Attia, Ilana Coven, ed. (1994). Science in the Light of Torah: A B'Or Ha'Torah Reader. Jason Aronson. ISBN 9781568210346.

- ^ Hort, William Jillard (1822). A General View of the Sciences and Arts. hlm. 182.

- ^ Kaler, James B. (2002). The Ever-changing Sky: A Guide to the Celestial Sphere. hlm. 25.

Pustaka

- Crowe, Michael J. (1990). Theories of the World from Antiquity to the Copernican Revolution. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 0486261735.

- Dreyer, J.L.E. (1953). A History of Astronomy from Thales to Kepler. New York: Dover Publications.

- Evans, James (1998). The History and Practice of Ancient Astronomy. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Heath, Thomas (1913). Aristarchus of Samos. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Hoyle, Fred (1973). Nicolaus Copernicus.

- Koestler, Arthur (1986) [1959]. The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe. Penguin Books. ISBN 014055212X. 1990 reprint: ISBN 0140192468.

- Kuhn, Thomas S. (1957). The Copernican Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674171039.

- Linton, Christopher M. (2004). From Eudoxus to Einstein—A History of Mathematical Astronomy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521827508.

- Walker, Christopher, ed. (1996). Astronomy Before the Telescope. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 0714117463.