Geosentrisme: Perbedaan antara revisi

JohnThorne (bicara | kontrib) Tidak ada ringkasan suntingan |

JohnThorne (bicara | kontrib) Tidak ada ringkasan suntingan |

||

| Baris 5: | Baris 5: | ||

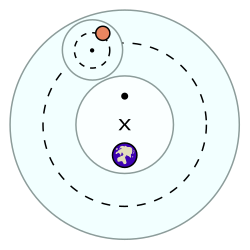

'''Geosentrisme''' atau disebut '''Teori Geosentrik''', '''Model Geosentrik''' (bahasa Inggris: '''geocentric model''' atau '''geocentrism''', '''Ptolemaic system''') adalah istilah [[astronomi]] yang menggambarkan alam semesta dengan [[bumi]] sebagai pusatnya dan pusat pergerakan semua benda-benda langit. Model ini menjadi sistem kosmologi predominan pada budaya kuno misalnya [[Yunani kuno]], yang meliputi sistem-sistem terkenal yang dikemukakan oleh [[Aristoteles]] and [[Claudius Ptolemaeus]].<ref name= "Lawson2004"/> |

'''Geosentrisme''' atau disebut '''Teori Geosentrik''', '''Model Geosentrik''' (bahasa Inggris: '''geocentric model''' atau '''geocentrism''', '''Ptolemaic system''') adalah istilah [[astronomi]] yang menggambarkan alam semesta dengan [[bumi]] sebagai pusatnya dan pusat pergerakan semua benda-benda langit. Model ini menjadi sistem kosmologi predominan pada budaya kuno misalnya [[Yunani kuno]], yang meliputi sistem-sistem terkenal yang dikemukakan oleh [[Aristoteles]] and [[Claudius Ptolemaeus]].<ref name= "Lawson2004"/> |

||

Dua pengamatan umum mendukung pandangan bahwa Bumi adalah pusat dari alam semesta. Pengamatan pertama adalah bintang-bintang, matahari dan planet-planet nampak berputar mengitari bumi setiap hari, membuat bumi adalah pusat sistem ini. Lebih lanjut, setiap bintang berada pada suatu bulatan stelar atau selestial ("''stellar sphere''" atau "''celestial sphere''"), di mana bumi adalah pusatnya, yang berkeliling setiap hari, di seputar garis yang menghubungkan kutub utara dan selatan sebagai aksisnya. Bintang-bintang yang terdekat dengan [[khatulistiwa]] nampak naik dan turun paling jauh, tetapi setiap bintang kembali ke titik terbitnya setiap hari.{{sfn|Kuhn|1957|pp=5-20}} Observasi umum kedua yang mendukung model geosentrik adalah bumi nampaknya tidak bergerak dari sudut pandang pengamat yang berada di bumi, bahwa bumi itu solid, stabil dan tetap di tempat. Dengan kata lain, benar-benar dalam posisi diam. |

|||

<!-- |

|||

Two commonly made observations supported the idea that Earth was the center of the Universe. The first observation was that the stars, the sun, and planets appear to revolve around Earth each day, making Earth the center of that system. Further, every star was on a "stellar" or "[[celestial sphere|celestial]]" sphere, of which the earth was the center, that rotated each day, sing a line through the north and south pole as an axis. The stars closest to the [[equator]] appeared to rise and fall the greatest distance, but each star circled back to its rising point each day.{{sfn|Kuhn|1957|pp=5-20}} The second common notion supporting the geocentric model was that the Earth does not seem to move from the perspective of an Earth bound observer, and that it is solid, stable, and unmoving. In other words, it is completely at rest. |

|||

Model geosentrik biasanya dikombinasi dengan suatu Bumi yang bulat oleh filsuf Romawi kuno dan abad pertengahan. Ini tidak sama dengan pandangan model [[Bumi datar]] yang disiratkan dalam sejumlah [[mitologi]], sebagaimana juga dalah kosmologi kitab-kitab suci dan Latin kuno.{{refn|group=n|Alam semesta Mesir secara isi sama dengan alam semesta Babel, yaitu digambarkan seperti kotak persegi panjang dengan orientasi utara-selatan dan dengn permukaan sedikit cembung, di mana Mesir adalah pusatnya. Pandangan astronomi Ibrani kuno yang serupa dapat dilihat dari tulisan-tulisan kitab suci, misalnya teori penciptaan semesta dan berbagai [[mazmur]] yang menyebut "cakrawala", bintang-bintang, matahari dan bumi. Orang Ibrani memandang bumi seakan-akan sebagai permukaan datar yang terdiri dari bagian padat dan cair, dan langit sebagai alam cahaya di mana benda-benda langit bergerak. Bumi ditopang oleh batu-batu penjuru dan tidak dapat digerakkan selain oleh [[Yahweh]] (misalnya dalam kaitan dengan gempa bumi). Menurut orang Ibrani, matahari dan bulan berjarak dekat satu sama lain<ref>{{cite book |chapter= Cosmology |title= Encyclopedia Americana |publisher= Grolier |edition= Online |year= 2012 |first= Giorgio |last= Abetti}}</ref>}}{{refn|group=n|Gambaran alam semesta dalam teks-teks Talmud adalah bumi di tengah ciptaan dengan langit sebagai bulatan yang dibentangkan di atasnya. Bumi biasanya digambarkan seperti sebuah piring yang dikelilingi oleh air. Yang menarik spekulasi kosmologi dan metafisika tidak ditanamkan dalam publik maupun dilestarikan dalam tulisan. Namun, dianggap lebih sebagai "rahasia-rahasia [[Taurat]] yang tidak seharusnya diturunkan semua orang dan kalangan" (Ketubot 112a). Meskipun studi penciptaan Allah tidak dilarang, spekulasi tentang "apa yang ada di atas, di bawah, yang ada sebelumnya dan yang kemudian" (Mishnah Hagigah: 2) dibatasi hanya untuk elite intelektual.<ref>{{cite book |chapter= Topic Overview: Judaism |title= Encyclopedia of Science and Religion |editor-first=J. Wentzel Vrede |editor-last= van Huyssteen |volume= 2 |location= New York |publisher= Macmillan Reference USA |year= 2003 |pages= 477–83 |first= Hava |last= Tirosh-Samuelson}}</ref>}}{{refn|group=n|Sebagaimana Midrash dan Talmud, Targum tidak does not think of a globe of the spherical earth, around which the sun revolves in 24 hours, but of a flat disk of the earth, above which the sun completes its semicircle in an average of 12 hours.<ref>{{cite journal |title= The distribution of land and sea on the Earth's surface according to Hebrew sources |first= Solomon |last= Gandz |journal= Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research |volume= 22 |year= 1953 |pages= 23–53}}</ref>}}<!-- The ancient Jewish [[Celestial cartography|uranography]] pictured a flat Earth over which was put a dome-shaped rigid canopy, named firmament (רקיע- rāqîa').{{refn|group=n|"firmament - The division made by God, according to the P account of creation, to restrain the cosmic water and form the sky (Gen. 1: 6-8). Hebrew cosmology pictured a flat earth, over which was a dome-shaped firmament, supported above the earth by mountains, and surrounded by waters. Holes or sluices (windows, Gen. 7: 11) allowed the water to fall as rain. The firmament was the heavens in which God set the sun (Ps. 19: 4) and the stars (Gen. 1: 14) on the fourth day of the creation. There was more water under the earth (Gen. 1: 7) and during the Flood the two great oceans joined up and covered the earth; sheol was at the bottom of the earth (Isa. 14: 9; Num. 16: 30)."<ref>{{cite book |chapter= firmament |title= Dictionary of the Bible |first= W. R. F. |last= Browning |publisher= Oxford University Press |year= 1997 |edition= Oxford Reference Online}}</ref>}}{{refn|group=n|The cosmographical structure assumed by this text is the ancient, traditional flat earth model that was common throughout the Near East and that persisted in Jewish tradition because of its place in the religiously authoritative biblical materials.<ref>{{cite book |title= The Early History Of Heaven |first= J. Edward |last= Wright |publisher= Oxford University Press |year= 2000 |page= 155 |ref={{Harvid|Wright|2000}}}}</ref>}}{{refn|group=n|“The term "firmament" (רקיע- rāqîa') denotes the atmosphere between the heavenly realm and the earth (Gen. 1:6-7, 20) where the celestial bodies move (Gen. 1:14-17). It can also be used as a synonym for "heaven" (Gen. 1:8; Ps. 19:2). This "firmament is part of the heavenly structure whether it is the equivalent of "heaven/sky" or is what separates it from the earth. […] The ancient Israelites also used more descriptive terms for how God created the celestial realm, and based on the collection of these more specific and illustrative terms, I would propose that they had two basic ideas of the composition of the heavenly realm. First is the idea that the heavenly realm was imagined as a vast cosmic canopy. The verb used to describe metaphorically how God stretched out this canopy over earth is הטנ (nātāh) "stretch out," or "spread." "I made the earth, and created humankind upon it; it was my hands that stretched out the heavens, and I commanded all their host (Isa. 45:12)." In the Bible this verb is used to describe the stretching out (pitching) of a tent. Since the texts that mention the stretching out of the sky are typically drawing on creation imagery, it seems that the figure intends to suggest that the heavens are Yahweh's cosmic tent. One can imagine ancient Israelites gazing up to the stars and comparing the canopy of the sky to the roofs of the tents under which they lived. In fact, if one were to look up at the ceiling of a dark tent with small holes in the roof during the daytime, the roof, with the sunlight shining through the holes, would look very much like the night sky with all its stars. The second image of the material composition of the heavenly realm involves a firm substance. The term רקיע (răqîa'), typically translated "firmament," indicates the expanse above the earth. The root רקע means "stamp out" or "forge." The idea of a solid, forged surface fits well with Ezekiel 1 where God's throne rests upon the רקיע (răqîa'). According to Genesis 1, the רקיע(rāqîa') is the sphere of the celestial bodies (Gen. 1:6-8, 14-17; cf. ben Sira 43:8). It may be that some imagined the עיקר to be a firm substance on which the celestial bodies rode during their daily journeys across the sky.”<ref>{{harvnb|Wright|2000|pp=55–6}}</ref>}}{{refn|group=n|In the course of the Second Temple Period Jews, and eventually Christians, began to describe the universe in new terms. The model of the universe inherited form the Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East of a flat earth completely surrounded by water with a heavenly realm of the gods arching above from horizon to horizon became obsolete. In the past the heavenly realm was for gods only. It was the place where all events on earth were determined by the gods, and their decisions were irrevocable. The gulf between the gods and humans could not have been greater. The evolution of Jewish cosmography in the course of the Second Temple Period followed developments in Hellenistic astronomy.<ref>{{harvnb|Wright|2000|p=201}}</ref>}}{{refn|group=n|What is described in Genesis 1:1 to 2:3 was the commonly accepted structure of the universe from at least late in the second millennium BCE to the fourth or third century BCE. It represents a coherent model for the experiences of the people of Mesopotamia through that period. It reflects a world-view that made sense of water coming from the sky and the ground as well as the regular apparent movements of the stars, sun, moon, and planets. There is a clear understanding of the restrictions on breeding between different species of animals and of the way in which human beings had gained control over what were, by then, domestic animals. There is also recognition of the ability of humans to change the environment in which they lived. This same understanding occurred also in the great creation stories of Mesopotamia; these stories formed the basis for the Jewish theological reflections of the Hebrew Scriptures concerning the creation of the world. The Jewish priests and theologians who constructed the narrative took accepted ideas about the structure of the world and reflected theologically on them in the light of their experience and faith. There was never any clash between Jewish and Babylonian people about the structure of the world, but only about who was responsible for it and its ultimate theological meaning. The envisaged structure is simple: Earth was seen as being situated in the middle of a great volume of water, with water both above and below Earth. A great dome was thought to be set above Earth (like an inverted glass bowl), maintaining the water above Earth in its place. Earth was pictured as resting on foundations that go down into the deep. These foundations secured the stability of the land as something that is not floating on the water and so could not be tossed about by wind and wave. The waters surrounding Earth were thought to have been gathered together in their place. The stars, sun, moon, and planets moved in their allotted paths across the great dome above Earth, with their movements defining the months, seasons, and year.<ref>{{cite book |chapter= Biblical Geology |title= Encyclopedia of Geology |editor1-first= Richard C. |editor1-last= Selley |editor2-first= L. Robin M. |editor2-last= Cocks |editor3-first= Ian R. |editor3-last= Plimer |volume= 1 |location= Amsterdam |publisher= Elsevier |year= 2005 |page= 253 |via= Gale Virtual Reference Library |accessdate= 2012-09-15}}</ref>}}{{refn|group=n|From Myth to Cosmos: The earliest speculations about the origin and nature of the world took the form of religious myths. Almost all ancient cultures developed cosmological stories to explain the basic features of the cosmos: Earth and its inhabitants, sky, sea, sun, moon, and stars. For example, for the Babylonians, the creation of the universe was seen as born from a primeval pair of human-like gods. In early Egyptian cosmology, eclipses were explained as the moon being swallowed temporarily by a sow or as the sun being attacked by a serpent. For the early Hebrews, whose account is preserved in the biblical book of Genesis, a single God created the universe in stages within the relatively recent past. Such pre-scientific cosmologies tended to assume a flat Earth, a finite past, ongoing active interference by deities or spirits in the cosmic order, and stars and planets (visible to the naked eye only as points of light) that were different in nature from Earth.<ref>{{cite book |last= Applebaum |first= Wilbur |chapter= Astronomy and Cosmology: Cosmology |title= Scientific Thought: In Context |editor1-first= K. Lee |editor1-last=Lerner |editor2-first= Brenda Wilmoth |editor2-last= Lerner |volume= 1 |location= Detroit |publisher= Gale |year= 2009 |pages= 20–31 |via= Gale Virtual Reference Library |accessdate= 2012-09-15}}</ref>}} |

|||

However, the ancient Greeks believed that the motions of the planets were circular and not elliptical, a view that was not challenged in [[Western culture]] until the 17th century through the synthesis of theories by [[Nicolaus Copernicus|Copernicus]] and [[Johannes Kepler|Kepler]]. |

However, the ancient Greeks believed that the motions of the planets were circular and not elliptical, a view that was not challenged in [[Western culture]] until the 17th century through the synthesis of theories by [[Nicolaus Copernicus|Copernicus]] and [[Johannes Kepler|Kepler]]. |

||

| Baris 108: | Baris 107: | ||

[[Morris Berman]] quotes survey results that show currently some 20% of the U.S. population believe that the sun goes around the Earth (geocentricism) rather than the Earth goes around the sun (heliocentricism), while a further 9% claimed not to know.<ref name= "Berman2006"/> Polls conducted by [[The Gallup Organization|Gallup]] in the 1990s found that 16% of Germans, 18% of Americans and 19% of Britons hold that the Sun revolves around the Earth.<ref name= "Crabtree1999"/> A study conducted in 2005 by Jon D. Miller of [[Northwestern University]], an expert in the public understanding of science and technology,<ref name= "MillerBio"/> found that about 20%, or one in five, of American adults believe that the Sun orbits the Earth.<ref name= "Dean2005"/> According to 2011 [[VTSIOM]] poll, 32% of [[Russians]] believe that the Sun orbits the Earth.<ref name= "RussianStudy2011"/> |

[[Morris Berman]] quotes survey results that show currently some 20% of the U.S. population believe that the sun goes around the Earth (geocentricism) rather than the Earth goes around the sun (heliocentricism), while a further 9% claimed not to know.<ref name= "Berman2006"/> Polls conducted by [[The Gallup Organization|Gallup]] in the 1990s found that 16% of Germans, 18% of Americans and 19% of Britons hold that the Sun revolves around the Earth.<ref name= "Crabtree1999"/> A study conducted in 2005 by Jon D. Miller of [[Northwestern University]], an expert in the public understanding of science and technology,<ref name= "MillerBio"/> found that about 20%, or one in five, of American adults believe that the Sun orbits the Earth.<ref name= "Dean2005"/> According to 2011 [[VTSIOM]] poll, 32% of [[Russians]] believe that the Sun orbits the Earth.<ref name= "RussianStudy2011"/> |

||

===Historical positions of the Roman Catholic hierarchy=== |

|||

The famous [[Galileo affair]] pitted the geocentric model against the claims of [[Galileo]]. In regards to the theological basis for such an argument, two Popes addressed the question of whether the use of phenomenological language would compel one to admit an error in Scripture. Both taught that it would not. [[Pope Leo XIII]] wrote: |

|||

:we have to contend against those who, making an evil use of physical science, minutely scrutinize the Sacred Book in order to detect the writers in a mistake, and to take occasion to vilify its contents. . . . There can never, indeed, be any real discrepancy between the theologian and the physicist, as long as each confines himself within his own lines, and both are careful, as St. Augustine warns us, "not to make rash assertions, or to assert what is not known as known." If dissension should arise between them, here is the rule also laid down by St. Augustine, for the theologian: "Whatever they can really demonstrate to be true of physical nature, we must show to be capable of reconciliation with our Scriptures; and whatever they assert in their treatises which is contrary to these Scriptures of ours, that is to Catholic faith, we must either prove it as well as we can to be entirely false, or at all events we must, without the smallest hesitation, believe it to be so." To understand how just is the rule here formulated we must remember, first, that the sacred writers, or to speak more accurately, the Holy Ghost "Who spoke by them, did not intend to teach men these things (that is to say, the essential nature of the things of the visible universe), things in no way profitable unto salvation." Hence they did not seek to penetrate the secrets of nature, but rather described and dealt with things in more or less figurative language, or in terms which were commonly used at the time, and which in many instances are in daily use at this day, even by the most eminent men of science. Ordinary speech primarily and properly describes what comes under the senses; and somewhat in the same way the sacred writers-as the Angelic Doctor also reminds us – `went by what sensibly appeared," or put down what God, speaking to men, signified, in the way men could understand and were accustomed to. ([[Providentissimus Deus]] 18). |

|||

Maurice Finocchiaro, author of a book on the Galileo affair, notes that this is "a view of the relationship between biblical interpretation and scientific investigation that corresponds to the one advanced by Galileo in the "[[Letter to the Grand Duchess Christina]]".<ref name="Finocchiaro1989"/> [[Pope Pius XII]] repeated his predecessor's teaching: |

|||

:The first and greatest care of Leo XIII was to set forth the teaching on the truth of the Sacred Books and to defend it from attack. Hence with grave words did he proclaim that there is no error whatsoever if the sacred writer, speaking of things of the physical order "went by what sensibly appeared" as the Angelic Doctor says,[5] speaking either "in figurative language, or in terms which were commonly used at the time, and which in many instances are in daily use at this day, even among the most eminent men of science." For "the sacred writers, or to speak more accurately – the words are St. Augustine's – [6] the Holy Spirit, Who spoke by them, did not intend to teach men these things – that is the essential nature of the things of the universe – things in no way profitable to salvation"; which principle "will apply to cognate sciences, and especially to history,"[7] that is, by refuting, "in a somewhat similar way the fallacies of the adversaries and defending the historical truth of Sacred Scripture from their attacks ([[Divino Afflante Spiritu]] 3). |

|||

In 1664 [[Alexander VII]] republished the ''[[Index Librorum Prohibitorum]]'' (''List of Prohibited Books'') and attached the various decrees connected with those books, including those concerned with heliocentrism. He stated in a [[Papal Bull]] that his purpose in doing so was that "the succession of things done from the beginning might be made known [''quo rei ab initio gestae series innotescat'']."<ref name= "Alexandri VII1664"/> |

|||

The position of the curia evolved slowly over the centuries towards permitting the heliocentric view. In 1757, during the papacy of Benedict XIV, the Congregation of the Index withdrew the decree which prohibited ''all'' books teaching the earth's motion, although the ''Dialogue'' and a few other books continued to be explicitly included. In 1820, the Congregation of the Holy Office, with the pope's approval, decreed that Catholic astronomer [[Joseph Settele]] was allowed to treat the earth's motion as an established fact. In 1822, the Congregation of the Holy Office removed the prohibition on the publication of books treating of the earth's motion in accordance with modern astronomy and Pope Pius VII ratified the decision. The 1835 edition of the Catholic Index of Prohibited Books for the first time omits the ''Dialogue'' from the list.<ref name="Finocchiaro1989"/> In a [[papal encyclical]] written in 1921 [[Pope Benedict XV]] stated that, "though this earth on which we live may not be the center of the universe as at one time was thought, it was the scene of the original happiness of our first ancestors, witness of their unhappy fall, as too of the Redemption of mankind through the Passion and Death of Jesus Christ."<ref name= "BenedictXV1921"/> In 1965 the [[Second Vatican Council]] stated that, "Consequently, we cannot but deplore certain habits of mind, which are sometimes found too among Christians, which do not sufficiently attend to the rightful independence of science and which, from the arguments and controversies they spark, lead many minds to conclude that faith and science are mutually opposed."<ref name= "PaulIV19665"/> The footnote on this statement is to Msgr. Pio Paschini's, ''Vita e opere di Galileo Galilei'', 2 volumes, Vatican Press (1964). And [[Pope John Paul II]] regretted the treatment which Galileo received, in a speech to the [[Pontifical Academy of Sciences]] in 1992. The Pope declared the incident to be based on a "tragic mutual miscomprehension". He further stated: |

|||

:Cardinal Poupard has also reminded us that the sentence of 1633 was not irreformable, and that the debate which had not ceased to evolve thereafter, was closed in 1820 with the imprimatur given to the work of Canon Settele. . . . The error of the theologians of the time, when they maintained the centrality of the earth, was to think that our understanding of the physical world's structure was, in some way, imposed by the literal sense of Sacred Scripture. Let us recall the celebrated saying attributed to Baronius "Spiritui Sancto mentem fuisse nos docere quomodo ad coelum eatur, non quomodo coelum gradiatur". In fact, the Bible does not concern itself with the details of the physical world, the understanding of which is the competence of human experience and reasoning. There exist two realms of knowledge, one which has its source in Revelation and one which reason can discover by its own power. To the latter belong especially the experimental sciences and philosophy. The distinction between the two realms of knowledge ought not to be understood as opposition.<ref name= "John PaulII1992"/> |

|||

===Orthodox Judaism=== |

|||

Some [[Orthodox Judaism|Orthodox Jewish]] leaders, particularly the [[Lubavitcher Rebbe]], maintain a geocentric model of the universe based on the aforementioned Biblical verses and an interpretation of [[Maimonides]] to the effect that he ruled that the earth is orbited by the sun.<ref name="Nussbaum2007"/><ref name= "Nussbaum2002"/> The [[Lubavitcher Rebbe]] also explained that geocentrism is defensible based on the [[theory of Relativity]], which establishes that "when two bodies in space are in motion relative to one another, ... science declares with absolute certainty that from the scientific point of view both possibilities are equally valid, namely that the earth revolves around the sun, or the sun revolves around the earth."<ref name="SchneersohnGotfryd2003"/> |

|||

While geocentrism is important in Maimonides' calendar calculations,<ref name= "Mishneh Torah"/> the great majority of Jewish religious scholars, who accept the divinity of the Bible and accept many of his rulings as legally binding, do not believe that the Bible or Maimonides command a belief in geocentrism.<ref name="Nussbaum2002" /><ref name= "Rabinowitz1987"/> |

|||

However, there is some evidence that geocentrist beliefs are becoming increasingly common among Orthodox Jews.<ref name="Nussbaum2007" /><ref name="Nussbaum2002" /> |

|||

===Islam=== |

|||

Prominent cases of modern geocentrism in Islam are very isolated. Very few individuals promoted a geocentric view of the universe. One of them was the Grand Mufti of Saudi Arabia from 1993 to 1999, [[Abd al-Aziz ibn Abd Allah ibn Baaz#Cosmology|Ibn Baz]],who promoted the view between 1966 and 1985. |

|||

== Planetariums == |

|||

The geocentric (Ptolemaic) model of the [[solar system]] is still of interest to [[planetarium]] makers, as, for technical reasons, a Ptolemaic-type motion for the planet light apparatus has some advantages over a Copernican-type motion.<ref name= "Hort1822"/> The [[celestial sphere]], still used for teaching purposes and sometimes for navigation, is also based on a geocentric system<ref name= "Kaler2002"/> which in effect ignores parallax. However this effect is negligible at the scale of accuracy that applies to a planetarium. |

|||

== Geocentric models in fiction == |

|||

[[Alternate history]] [[science fiction]] has produced some literature of interest on the proposition that some alternate universes and Earths might indeed have laws of physics and cosmologies that are Ptolemaic and Aristotelian in design. This subcategory began with [[Philip Jose Farmer|Philip Jose Farmer's]] [[short story]], ''[[Sail On! Sail On!]]'' (1952), where Columbus has access to [[radio]] technology, and where his [[Spain|Spanish]]-financed exploratory and trade fleet sail off the edge of the (flat) world in his geocentric alternate universe in 1492, instead of discovering [[North America]] and [[South America]]. |

|||

[[Richard Garfinkle|Richard Garfinkle's]] ''[[Celestial Matters]]'' (1996) is set in a more elaborated geocentric cosmos, where Earth is divided by two contending factions, the [[Classical Greece]]-dominated [[Delian League]] and the [[China|Chinese]] Middle Kingdom, both of which are capable of flight within an alternate universe based on [[Ptolemaic astronomy]], [[Aristotle|Aristotle's]] physics and [[Taoist]] thought. Unfortunately, both superpowers have been fighting a thousand-year war since the time of [[Alexander the Great]]. |

|||

In the [[C.S. Lewis]] novel, [[The Voyage of the Dawn Treader]], one of the [[Chronicles of Narnia]] series, the characters involved set out on a naval voyage to discover the edge of the world. The events of the book follow their journey across a flat, geocentric "world" and beyond its fringes. |

|||

== See also == |

|||

*[[Celestial spheres]] |

|||

*[[Firmament]] |

|||

*[[Religious cosmology]] |

|||

*[[Flat Earth]] |

|||

== Notes == |

|||

{{reflist|group=n|colwidth=30em}} |

|||

== References == |

|||

{{reflist|colwidth=30em|refs= |

|||

<ref name= "Lawson2004">{{cite book |last= Lawson |first= Russell M. |year= 2004 |title= Science in the Ancient World: An Encyclopedia |pages= [http://books.google.com/?id=1AY1ALzh9V0C&pg=PA30 29–30] |

|||

|publisher= [[ABC-CLIO]] |isbn= 1851095349 |ref={{Harvid|Lawson|2004}}}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Fraser2006">{{cite book |last= Fraser |first= Craig G. |title= The Cosmos: A Historical Perspective |year= 2006 |page= 14}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Hetherington2006">{{cite book |last= Hetherington |first= Norriss S. |title= Planetary Motions: A Historical Perspective |year= 2006 |page= 28}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Goldstein1967">{{cite journal |title= The Arabic version of Ptolemy's planetary hypothesis |first= Bernard R. |last= Goldstein |page= 6 |journal= Transactions of the American Philosophical Society |year= 1967 |volume= 57 |issue= pt. 4 |jstor= 1006040}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Rufus1939">{{Cite journal |title= The influence of Islamic astronomy in Europe and the far east |last= Rufus |first= W. C. |journal= Popular Astronomy |volume= 47 |issue= 5 |date=May 1939 |pages= 233–8}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Hartner1955">{{cite journal |first= Willy |last= Hartner |title= The Mercury horoscope of Marcantonio Michiel of Venice |journal= Vistas in Astronomy |volume= 1 |year= 1955 |pages= 118–22}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Goldstein1972">{{cite journal |first= Bernard R. |last= Goldstein |year= 1972 |title= Theory and observation in medieval astronomy |journal= Isis |volume= 63 |issue= 1 |page= 41}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Gale">{{Cite book |chapter= Ptolemaic Astronomy, Islamic Planetary Theory, and Copernicus's Debt to the Maragha School |title= Science and Its Times |publisher= [[Thomson Gale]] |year= 2006}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Setia2004">{{Cite journal |title= Fakhr Al-Din Al-Razi on physics and the nature of the physical world: A preliminary survey |first= Adi |last= Setia |journal= Islam & Science |volume= 2 |year= 2004}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Saliba1994">{{cite book |last= Saliba |first= George |authorlink= George Saliba |year= 1994 |title= A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam |pages= 233–234, 240 |publisher= [[New York University Press]] |isbn= 0814780237}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Dallal1999">{{cite book |first= Ahmad |last= Dallal |year= 1999 |chapter= Science, Medicine and Technology |title= The Oxford History of Islam |page= 171 |editor-first= John |editor-last= Esposito |editor-link= John Esposito |location= New York |publisher= [[Oxford University Press]]}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Guessoun2008">{{cite journal |last= Guessoum |first= N. |date=June 2008 |title= Copernicus and Ibn Al-Shatir: Does the Copernican revolution have Islamic roots? |journal= The Observatory |volume= 128 |pages= 231–9}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Ragep2001a">{{Cite journal |last= Ragep |first= F. Jamil |year= 2001 |title= Tusi and Copernicus: The Earth's motion in context |journal= Science in Context |volume= 14 |issue= 1-2 |pages= 145–163 |publisher= [[Cambridge University Press]]}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Ragep2001b">{{Cite journal |last= Ragep |first= F. Jamil |year= 2001 |title= Freeing astronomy from philosophy: An aspect of Islamic influence on science |journal= Osiris |series= 2nd Series |volume= 16 |issue= Science in Theistic Contexts: Cognitive Dimensions |pages= 49–64, 66–71 |doi=10.1086/649338}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Huff2003">{{cite book |last= Huff |first= Toby E. |title= The Rise of Early Modern Science: Islam, China and the West |year= 2003 |publisher= Cambridge University Press |isbn= 9780521529945 |page= [http://books.google.com/books?id=DA3fkX5wQMUC&pg=PA58 58]}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="KirmaniSingh2005">{{cite book |last1= Kirmani |first1= M. Zaki |last2= Singh |first2= Nagendra Kr |title= Encyclopaedia of Islamic Science and Scientists: A-H |year= 2005 |publisher= Global Vision | isbn=9788182200586}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "JohansenRosenmeier1998">{{cite book |first1= K. F. |last1=Johansen |first2= H. |last2= Rosenmeier |title= A History of Ancient Philosophy: From the Beginnings to Augustine |year= 1998 |page= 43}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Sarton1953">{{cite book |first= George |last= Sarton |title= Ancient Science Through the Golden Age of Greece |year= 1953 |page= 290}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Eastwood1992">{{Cite journal |volume= 23 |page= 233 |last= Eastwood |first= B. S. |title= Heraclides and heliocentrism – Texts diagrams and interpretations |journal= Journal for the History of Astronomy |date= 1992-11-01}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Lindberg2010">{{cite book |last= Lindberg |first= David C. |title= The Beginnings of Western Science: The European Scientific Tradition in Philosophical, Religious, and Institutional Context, Prehistory to A.D. 1450 |edition= 2nd |year= 2010 |publisher= University of Chicago Press |isbn= 9780226482040 |page= [http://books.google.com/books?id=dPUBAkIm2lUC&pg=PA197 197]}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Russell1945">{{cite book |last= Russell |first= Bertrand |authorlink= Bertrand Russell |title= [[A History of Western Philosophy]] |origyear= 1945 |year= 2013 |publisher= Routledge |page= 215 |isbn= 9781134343676}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Finocchiaro2008">{{cite book |last= Finocchiaro |first= Maurice A. |title= The Essential Galileo |location= Indianapolis, IL |publisher= Hackett |year= 2008 |page= 49}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Densmore2004">{{cite book |title= Selections from Newton's Principia |editor-first= Dana |editor-last= Densmore |publisher= Green Lion Press |year= 2004 |page= 12}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Babinski1995">{{cite journal |editor-last= Babinski |editor-first= E. T. |journal= Cretinism of Evilution |issue= 2 |title= Excerpts from Frank Zindler's 'Report from the center of the universe' and 'Turtles all the way down' |url= http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/ce/2/part3.html |publisher= [[TalkOrigins Archive]] |year= 1995 |accessdate= 2013-12-01}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Graebner1902">{{cite journal |title= Science and the church |journal= Theological Quarterly |first= A. L. |last= Graebner |pages= [http://books.google.com/books?id=cxsRAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA37 37–45] |year= 1902 |publisher= Lutheran Synod of Missouri, Ohio and other states, Concordia Publishing |location= St. Louis, MO |volume= 6}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Numbers1993">{{cite book |title= The Creationists: The Evolution of Scientific Creationism |publisher= University of California Press |last= Numbers |first= Ronald L. |authorlink= Ronald L. Numbers |year= 1993 |page= 237 |isbn= 0520083938}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Sefton2006">{{cite news |url= http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=_1kaAAAAIBAJ&sjid=XCYEAAAAIBAJ&dq=robert-sungenis&pg=6714%2C4991566 |title= In this world view, the sun revolves around the earth |first= Dru |last= Sefton |newspaper= [[Times-News (Hendersonville, North Carolina)|Times-News]] |location= Hendersonville, NC |date= 2006-03-30 |page= 5A}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Berman2006">{{cite book |last= Berman |first= Morris |authorlink= Morris Berman |title= Dark Ages America: The Final Phase of Empire |year= 2006 |publisher= W.W. Norton & Company |isbn= 9780393058666}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Crabtree1999">{{cite web |url= http://www.gallup.com/poll/3742/new-poll-gauges-americans-general-knowledge-levels.aspx |title= New Poll Gauges Americans' General Knowledge Levels |first= Steve |last= Crabtree |publisher= [[The Gallup Organization|Gallup]] |date= 1999-07-06}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "MillerBio">{{cite web |url= http://www.cmb.northwestern.edu/faculty/jon_miller.htm |title= Jon D. Miller |work= Northwestern University website |accessdate= 2007-07-19}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Dean2005">{{cite news |url= http://www.nytimes.com/2005/08/30/science/30profile.html?ex=1184990400&en=2fb126c3132f89ae&ei=5070 |title=Scientific savvy? In U.S., not much |first= Cornelia |last= Dean |date= 2005-08-30 |newspaper= New York Times |accessdate= 2007-07-19}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "RussianStudy2011">{{citation |url= http://wciom.ru/index.php?id=459&uid=111345 |title= 'СОЛНЦЕ - СПУТНИК ЗЕМЛИ', ИЛИ РЕЙТИНГ НАУЧНЫХ ЗАБЛУЖДЕНИЙ РОССИЯН |trans_title= 'Sun-earth', or rating scientific fallacies of Russians |issue= Пресс-выпуск №1684 <nowiki>[</nowiki>Press release no. 1684<nowiki>]</nowiki> |date= 2011-02-08 |language= ru |publisher= ВЦИОМ <nowiki>[</nowiki>[[VTSIOM|All-Russian Center for the Study of Public Opinion]]<nowiki>]</nowiki> |postscript= .}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Finocchiaro1989">{{cite book |title= The Galileo Affair: A Documentary History |first= Maurice A. |last= Finocchiaro |location= Berkeley |publisher= University of California Press |year= 1989 |page= [http://books.google.com/books?id=k7D1CXFBl2gC&pg=PA307 307] |isbn= 9780520066625}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Alexandri VII1664">{{cite book |title= Index librorum prohibitorum Alexandri VII |url= http://books.google.com/books?id=PSVCAAAAcAAJ |year= 1664 |publisher= Ex typographia Reurendae Camerae Apostolicae |location= Rome |language= Latin |page= v}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "BenedictXV1921">{{cite web |url= http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xv/encyclicals/documents/hf_ben-xv_enc_30041921_in-praeclara-summorum_en.html |title= In Praeclara Summorum: Encyclical of Pope Benedict XV on Dante to Professors and Students of Literature and Learning in the Catholic World |date= 1921-04-30 |location= Rome |page= § 4 |nopp=y}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "PaulIV19665">{{cite web |url= http://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_cons_19651207_gaudium-et-spes_en.html |title= Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World 'Gaudium Et Spes' Promulgated by His Holiness, Pope Paul IV on December 7, 1965 |page= § 36 |nopp=y}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "John PaulII1992">{{cite journal |title= Faith can never conflict with reason |url= http://www.its.caltech.edu/~nmcenter/sci-cp/sci-9211.html |journal= L'Osservatore Romano |volume= 44 |issue= 1264 |date= 1992-11-04 |author= Pope John Paul II}} (Published English translation).</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Nussbaum2007">{{Cite journal |url= http://www.skeptic.com/the_magazine/featured_articles/v12n03_orthodox_judaism_and_evolution.html |title= Orthodox Jews & science: An empirical study of their attitudes toward evolution, the fossil record, and modern geology |accessdate= 2008-12-18 |last= Nussbaum |first= Alexander |date= 2007-12-19 |journal= Skeptic Magazine}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Nussbaum2002">{{cite journal |first= Alexander |last= Nussbaum |title= Creationism and geocentrism among Orthodox Jewish scientists |journal= Reports of the National Center for Science Education |date=January–April 2002 |pages= 38–43}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="SchneersohnGotfryd2003">{{cite book |last1= Schneersohn |first1= Menachem Mendel |authorlink1= Menachem Mendel Schneerson |last2= Gotfryd |first2= Arnie |title= Mind over Matter: The Lubavitcher Rebbe on Science, Technology and Medicine |pages= [http://books.google.com/books?id=FmabnhsgSVAC&pg=PA76 76ff.]; cf. xvi-xvii, [http://books.google.com/books?id=FmabnhsgSVAC&pg=PA69 69], [http://books.google.com/books?id=FmabnhsgSVAC&pg=PA100 100–1], [http://books.google.com/books?id=FmabnhsgSVAC&pg=PA171 171–2], [http://books.google.com/books?id=FmabnhsgSVAC&pg=PA408 408ff.] |year= 2003 |publisher= Shamir |isbn= 9789652930804}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Mishneh Torah">{{cite book |title= Mishneh Torah |url= http://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/947929/jewish/Chapter-Eleven.htm |chapter= Sefer Zemanim: Kiddush HaChodesh: Chapter 11 |page= Halacha 13–14 |nopp=y |others= Translated by Touger, Eliyahu |publisher= Chabad-Lubavitch Media Center}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Rabinowitz1987">{{cite web |url= http://www.pages.nyu.edu/%7Eair1/GeoCentrism%20&%20EgoCentrism,%20Existentialist%20Despair%20&%20Significance.htm |first= Avi |last= Rabinowitz |year= 1987 |title= EgoCentrism and GeoCentrism; Human Significance and Existential Despair; Bible and Science; Fundamentalism and Skepticalism | work= Science & Religion | accessdate=2013-12-01}} Published in {{cite book |editor1-last= Branover |editor1-first= Herman |editor2-last=Attia |editor2-first= Ilana Coven |title= Science in the Light of Torah: A B'Or Ha'Torah Reader |year= 1994 |publisher= Jason Aronson |isbn=9781568210346}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Hort1822">{{cite book |first= William Jillard |last= Hort |title= A General View of the Sciences and Arts |year= 1822 |page= 182}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Kaler2002">{{cite book |last= Kaler |first= James B. |title= The Ever-changing Sky: A Guide to the Celestial Sphere |year= 2002 |page= 25}}</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

== Bibliography == |

|||

* {{cite book | title = Theories of the World from Antiquity to the Copernican Revolution | last = Crowe |first= Michael J. | publisher = Dover Publications | year = 1990 | location = Mineola, NY | isbn = 0486261735 | ref = {{Harvid|Crowe|1990}}}} |

|||

*{{cite book | title= A History of Astronomy from Thales to Kepler | last= Dreyer |first= J.L.E. | publisher= Dover Publications | year= 1953 | url=http://www.archive.org/details/historyofplaneta00dreyuoft | location= New York |

|||

| ref={{Harvid|Dreyer|1953}} | authorlink= John Louis Emil Dreyer}} |

|||

*{{cite book |last= Evans |first= James |title= The History and Practice of Ancient Astronomy |location= New York |publisher= Oxford University Press |year= 1998 |ref={{Harvid|Evans|1998}}}} |

|||

*{{cite book |last= Heath |first= Thomas |authorlink= T. L. Heath |title= Aristarchus of Samos |location= Oxford |publisher= Clarendon Press |year= 1913|ref={{Harvid|Heath|1913}}}} |

|||

*{{cite book |authorlink= Sir Fred Hoyle |last= Hoyle |first= Fred |title= Nicolaus Copernicus |year= 1973|ref={{Harvid|Hoyle|1973}}}} |

|||

*{{cite book |authorlink= Arthur Koestler |last= Koestler |first= Arthur |title= The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe |origyear= 1959 |publisher= Penguin Books |year= 1986 |isbn= 014055212X |ref={{Harvid|Koestler|1959}}}} 1990 reprint: ISBN 0140192468. |

|||

*{{cite book |authorlink= Thomas Samuel Kuhn |last= Kuhn |first= Thomas S. |title= The Copernican Revolution |location= Cambridge |publisher= Harvard University Press |year= 1957 |isbn= 0674171039 |ref={{Harvid|Kuhn|1957}}}} |

|||

*{{cite book | title= From Eudoxus to Einstein—A History of Mathematical Astronomy | last= Linton |first= Christopher M. | publisher= Cambridge University Press | year= 2004 | location= Cambridge | isbn= 9780521827508 | ref={{Harvid|Linton|2004}}}} |

|||

*{{cite book |editor-last= Walker |editor-first= Christopher |title= Astronomy Before the Telescope |location= London |publisher= British Museum Press |year= 1996 |isbn= 0714117463 |ref={{Harvid|Walker|1996}}}} |

|||

== External links == |

|||

* [http://www.astro.utoronto.ca/~zhu/ast210/geocentric.html Another demonstration of the complexity of observed orbits when assuming a geocentric model of the solar system] |

|||

* [http://www.astronomy.ohio-state.edu/~pogge/Ast161/Movies/#ptolemaic Geocentric Perspective animation of the Solar System in 150AD] |

|||

* [http://library.thinkquest.org/29033/history/ptolemy.htm Ptolemy’s system of astronomy] <!-- replaces commented-out links --> |

|||

* [http://galileo.rice.edu/sci/theories/ptolemaic_system.html The Galileo Project – Ptolemaic System] |

|||

{{Greek astronomy}} |

|||

<!--{{Link FA|ja}}--> |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Geocentric Model}} |

|||

[[Category:Ancient Greek astronomy]] |

|||

[[Category:History of astronomy]] |

|||

[[Category:Celestial coordinate system]] |

|||

[[Category:Obsolete scientific theories]] |

|||

[[Category:Scientific modeling]] |

|||

[[Category:History of ideas]] |

|||

[[Category:Early scientific cosmologies]] |

|||

[[Category:History of astrology]] |

|||

[[Category:Chauvinism]] |

|||

[[Category:Copernican Revolution]] |

|||

{{Link FA|he}} |

|||

]]s, and [[naked eye planets]] circled Earth, including the noteworthy systems of [[Aristotle]] (see [[Aristotelian physics]]) and [[Ptolemy]].<ref name= "Lawson2004"/> |

|||

<!-- |

|||

Two commonly made observations supported the idea that Earth was the center of the Universe. The first observation was that the stars, the sun, and planets appear to revolve around Earth each day, making Earth the center of that system. Further, every star was on a "stellar" or "[[celestial sphere|celestial]]" sphere, of which the earth was the center, that rotated each day, using a line through the north and south pole as an axis. The stars closest to the [[equator]] appeared to rise and fall the greatest distance, but each star circled back to its rising point each day.{{sfn|Kuhn|1957|pp=5-20}} The second common notion supporting the geocentric model was that the Earth does not seem to move from the perspective of an Earth bound observer, and that it is solid, stable, and unmoving. In other words, it is completely at rest. |

|||

The geocentric model was usually combined with a [[spherical Earth]] by ancient Roman and medieval philosophers. It is not the same as the older [[flat Earth]] model implied in some [[mythology]], as was the case with the biblical and postbiblical Latin cosmology.{{refn|group=n|The Egyptian universe was substantially similar to the Babylonian universe; it was pictured as a rectangular box with a north-south orientation and with a slightly concave surface, with Egypt in the center. A good idea of the similarly primitive state of Hebrew astronomy can be gained from Biblical writings, such as the Genesis creation story and the various Psalms that extol the firmament, the stars, the sun, and the earth. The Hebrews saw the earth as an almost flat surface consisting of a solid and a liquid part, and the sky as the realm of light in which heavenly bodies move. The earth rested on cornerstones and could not be moved except by Jehovah (as in an earthquake). According to the Hebrews, the sun and the moon were only a short distance from one another<ref>{{cite book |chapter= Cosmology |title= Encyclopedia Americana |publisher= Grolier |edition= Online |year= 2012 |first= Giorgio |last= Abetti}}</ref>}}{{refn|group=n|The picture of the universe in Talmudic texts has the Earth in the center of creation with heaven as a hemisphere spread over it. The Earth is usually described as a disk encircled by water. Interestingly, cosmological and metaphysical speculations were not to be cultivated in public nor were they to be committed to writing. Rather, they were considered as "secrets of the Torah not to be passed on to all and sundry" (Ketubot 112a). While study of God's creation was not prohibited, speculations about "what is above, what is beneath, what is before, and what is after" (Mishnah Hagigah: 2) were restricted to the intellectual elite.<ref>{{cite book |chapter= Topic Overview: Judaism |title= Encyclopedia of Science and Religion |editor-first=J. Wentzel Vrede |editor-last= van Huyssteen |volume= 2 |location= New York |publisher= Macmillan Reference USA |year= 2003 |pages= 477–83 |first= Hava |last= Tirosh-Samuelson}}</ref>}}{{refn|group=n|Like the Midrash and the Talmud, the Targum does not think of a globe of the spherical earth, around which the sun revolves in 24 hours, but of a flat disk of the earth, above which the sun completes its semicircle in an average of 12 hours.<ref>{{cite journal |title= The distribution of land and sea on the Earth's surface according to Hebrew sources |first= Solomon |last= Gandz |journal= Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research |volume= 22 |year= 1953 |pages= 23–53}}</ref>}} The ancient Jewish [[Celestial cartography|uranography]] pictured a flat Earth over which was put a dome-shaped rigid canopy, named firmament (רקיע- rāqîa').{{refn|group=n|"firmament - The division made by God, according to the P account of creation, to restrain the cosmic water and form the sky (Gen. 1: 6-8). Hebrew cosmology pictured a flat earth, over which was a dome-shaped firmament, supported above the earth by mountains, and surrounded by waters. Holes or sluices (windows, Gen. 7: 11) allowed the water to fall as rain. The firmament was the heavens in which God set the sun (Ps. 19: 4) and the stars (Gen. 1: 14) on the fourth day of the creation. There was more water under the earth (Gen. 1: 7) and during the Flood the two great oceans joined up and covered the earth; sheol was at the bottom of the earth (Isa. 14: 9; Num. 16: 30)."<ref>{{cite book |chapter= firmament |title= Dictionary of the Bible |first= W. R. F. |last= Browning |publisher= Oxford University Press |year= 1997 |edition= Oxford Reference Online}}</ref>}}{{refn|group=n|The cosmographical structure assumed by this text is the ancient, traditional flat earth model that was common throughout the Near East and that persisted in Jewish tradition because of its place in the religiously authoritative biblical materials.<ref>{{cite book |title= The Early History Of Heaven |first= J. Edward |last= Wright |publisher= Oxford University Press |year= 2000 |page= 155 |ref={{Harvid|Wright|2000}}}}</ref>}}{{refn|group=n|“The term "firmament" (רקיע- rāqîa') denotes the atmosphere between the heavenly realm and the earth (Gen. 1:6-7, 20) where the celestial bodies move (Gen. 1:14-17). It can also be used as a synonym for "heaven" (Gen. 1:8; Ps. 19:2). This "firmament is part of the heavenly structure whether it is the equivalent of "heaven/sky" or is what separates it from the earth. […] The ancient Israelites also used more descriptive terms for how God created the celestial realm, and based on the collection of these more specific and illustrative terms, I would propose that they had two basic ideas of the composition of the heavenly realm. First is the idea that the heavenly realm was imagined as a vast cosmic canopy. The verb used to describe metaphorically how God stretched out this canopy over earth is הטנ (nātāh) "stretch out," or "spread." "I made the earth, and created humankind upon it; it was my hands that stretched out the heavens, and I commanded all their host (Isa. 45:12)." In the Bible this verb is used to describe the stretching out (pitching) of a tent. Since the texts that mention the stretching out of the sky are typically drawing on creation imagery, it seems that the figure intends to suggest that the heavens are Yahweh's cosmic tent. One can imagine ancient Israelites gazing up to the stars and comparing the canopy of the sky to the roofs of the tents under which they lived. In fact, if one were to look up at the ceiling of a dark tent with small holes in the roof during the daytime, the roof, with the sunlight shining through the holes, would look very much like the night sky with all its stars. The second image of the material composition of the heavenly realm involves a firm substance. The term רקיע (răqîa'), typically translated "firmament," indicates the expanse above the earth. The root רקע means "stamp out" or "forge." The idea of a solid, forged surface fits well with Ezekiel 1 where God's throne rests upon the רקיע (răqîa'). According to Genesis 1, the רקיע(rāqîa') is the sphere of the celestial bodies (Gen. 1:6-8, 14-17; cf. ben Sira 43:8). It may be that some imagined the עיקר to be a firm substance on which the celestial bodies rode during their daily journeys across the sky.”<ref>{{harvnb|Wright|2000|pp=55–6}}</ref>}}{{refn|group=n|In the course of the Second Temple Period Jews, and eventually Christians, began to describe the universe in new terms. The model of the universe inherited form the Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East of a flat earth completely surrounded by water with a heavenly realm of the gods arching above from horizon to horizon became obsolete. In the past the heavenly realm was for gods only. It was the place where all events on earth were determined by the gods, and their decisions were irrevocable. The gulf between the gods and humans could not have been greater. The evolution of Jewish cosmography in the course of the Second Temple Period followed developments in Hellenistic astronomy.<ref>{{harvnb|Wright|2000|p=201}}</ref>}}{{refn|group=n|What is described in Genesis 1:1 to 2:3 was the commonly accepted structure of the universe from at least late in the second millennium BCE to the fourth or third century BCE. It represents a coherent model for the experiences of the people of Mesopotamia through that period. It reflects a world-view that made sense of water coming from the sky and the ground as well as the regular apparent movements of the stars, sun, moon, and planets. There is a clear understanding of the restrictions on breeding between different species of animals and of the way in which human beings had gained control over what were, by then, domestic animals. There is also recognition of the ability of humans to change the environment in which they lived. This same understanding occurred also in the great creation stories of Mesopotamia; these stories formed the basis for the Jewish theological reflections of the Hebrew Scriptures concerning the creation of the world. The Jewish priests and theologians who constructed the narrative took accepted ideas about the structure of the world and reflected theologically on them in the light of their experience and faith. There was never any clash between Jewish and Babylonian people about the structure of the world, but only about who was responsible for it and its ultimate theological meaning. The envisaged structure is simple: Earth was seen as being situated in the middle of a great volume of water, with water both above and below Earth. A great dome was thought to be set above Earth (like an inverted glass bowl), maintaining the water above Earth in its place. Earth was pictured as resting on foundations that go down into the deep. These foundations secured the stability of the land as something that is not floating on the water and so could not be tossed about by wind and wave. The waters surrounding Earth were thought to have been gathered together in their place. The stars, sun, moon, and planets moved in their allotted paths across the great dome above Earth, with their movements defining the months, seasons, and year.<ref>{{cite book |chapter= Biblical Geology |title= Encyclopedia of Geology |editor1-first= Richard C. |editor1-last= Selley |editor2-first= L. Robin M. |editor2-last= Cocks |editor3-first= Ian R. |editor3-last= Plimer |volume= 1 |location= Amsterdam |publisher= Elsevier |year= 2005 |page= 253 |via= Gale Virtual Reference Library |accessdate= 2012-09-15}}</ref>}}{{refn|group=n|From Myth to Cosmos: The earliest speculations about the origin and nature of the world took the form of religious myths. Almost all ancient cultures developed cosmological stories to explain the basic features of the cosmos: Earth and its inhabitants, sky, sea, sun, moon, and stars. For example, for the Babylonians, the creation of the universe was seen as born from a primeval pair of human-like gods. In early Egyptian cosmology, eclipses were explained as the moon being swallowed temporarily by a sow or as the sun being attacked by a serpent. For the early Hebrews, whose account is preserved in the biblical book of Genesis, a single God created the universe in stages within the relatively recent past. Such pre-scientific cosmologies tended to assume a flat Earth, a finite past, ongoing active interference by deities or spirits in the cosmic order, and stars and planets (visible to the naked eye only as points of light) that were different in nature from Earth.<ref>{{cite book |last= Applebaum |first= Wilbur |chapter= Astronomy and Cosmology: Cosmology |title= Scientific Thought: In Context |editor1-first= K. Lee |editor1-last=Lerner |editor2-first= Brenda Wilmoth |editor2-last= Lerner |volume= 1 |location= Detroit |publisher= Gale |year= 2009 |pages= 20–31 |via= Gale Virtual Reference Library |accessdate= 2012-09-15}}</ref>}} |

|||

However, the ancient Greeks believed that the motions of the planets were circular and not elliptical, a view that was not challenged in [[Western culture]] until the 17th century through the synthesis of theories by [[Nicolaus Copernicus|Copernicus]] and [[Johannes Kepler|Kepler]]. |

|||

The astronomical predictions of Ptolemy's geocentric model were used to prepare astrological charts for over 1500 years. The geocentric model held sway into the [[early modern]] age, but from the late 16th century onward was gradually [[Superseded scientific theories#Superseded astronomical and cosmological theories|superseded]] by the [[heliocentrism|heliocentric model]] of [[Nicolaus Copernicus|Copernicus]], [[Galileo Galilei|Galileo]] and [[Johannes Kepler|Kepler]]. However, the transition between these two theories met much resistance, not only from Christian theologians, who were reluctant to reject a theory that was in agreement with Bible passages (e.g. "Sun, stand you still upon Gibeon", Joshua 10:12 - King James 2000 Bible), but also from those who saw geocentrism as an accepted consensus that could not be subverted by a new, unknown theory. |

|||

== Ancient Greece == |

|||

[[File:Persectives of Anaximander's universe.png|thumb|right|350px|Illustration of Anaximander's models of the universe. On the left, daytime in summer; on the right, nighttime in winter.]] |

|||

The geocentric model entered [[Greek astronomy]] and philosophy at an early point; it can be found in [[Pre-Socratic philosophy]]. In the 6th century BC, [[Anaximander]] proposed a cosmology with the Earth shaped like a section of a pillar (a cylinder), held aloft at the center of everything. The Sun, Moon, and planets were holes in invisible wheels surrounding the Earth; through the holes, humans could see concealed fire. About the same time, the [[Pythagoreans]] thought that the Earth was a sphere (in accordance with observations of eclipses), but not at the center; they believed that it was in motion around an unseen fire. Later these views were combined, so most educated Greeks from the 4th century BC on thought that the Earth was a sphere at the center of the universe.<ref name= "Fraser2006"/> |

|||

In the 4th century BC, two influential Greek philosophers, [[Plato]] and his student [[Aristotle]], wrote works based on the geocentric model. According to Plato, the Earth was a sphere, stationary at the center of the universe. The stars and planets were carried around the Earth on [[Celestial spheres|spheres or circles]], arranged in the order (outwards from the center): Moon, Sun, Venus, Mercury, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, fixed stars, with the fixed stars located on the celestial sphere. In his "[[Myth of Er]]", a section of the ''[[Republic (dialogue)|Republic]]'', Plato describes the cosmos as the [[Spindle of Necessity]], attended by the [[Siren (mythology)|Siren]]s and turned by the three [[Moirai|Fates]]. [[Eudoxus of Cnidus]], who worked with Plato, developed a less mythical, more mathematical explanation of the planets' motion based on Plato's [[dictum]] stating that all [[phenomena]] in the heavens can be explained with uniform circular motion. Aristotle elaborated on Eudoxus' system. |

|||

In the fully developed Aristotelian system, the spherical Earth is at the center of the universe, and all other heavenly bodies are attached to 47–56 transparent concentric spheres which rotate around the Earth. (The number is so high because several spheres are needed for each planet.) These spheres, known as crystalline spheres, all moved at different uniform speeds to create the rotation of bodies around the Earth. They were composed of an incorruptible substance called [[Aether (classical element)|aether]]. Aristotle believed that the moon was in the innermost sphere and therefore touches the realm of Earth, causing the dark spots ([[Macula (planetary geology)|macula]]) and the ability to go through [[lunar phases]]. He further described his system by explaining the natural tendencies of the terrestrial elements: earth, water, fire, air, as well as celestial aether. His system held that earth was the heaviest element, with the strongest movement towards the center, thus water formed a layer surrounding the sphere of earth. The tendency of air and fire, on the other hand, was to move upwards, away from the center, with fire being lighter than air. Beyond the layer of fire, where the solid spheres of aether in which the celestial bodies were embedded. They, themselves, were also entirely composed of aether. |

|||

Adherence to the geocentric model stemmed largely from several important observations. First of all, if the Earth did move, then one ought to be able to observe the shifting of the fixed stars due to stellar [[parallax]]. In short, if the earth was moving, the shapes of the [[constellation]]s should change considerably over the course of a year. If they did not appear to move, the stars are either much further away than the Sun and the planets than previously conceived, making their motion undetectable, or in reality they are not moving at all. Because the stars were actually much further away than Greek astronomers postulated (making movement extremely subtle), stellar parallax was not detected until the 19th century. Therefore, the Greeks chose the simpler of the two explanations. The lack of any observable parallax was considered a fatal flaw in any non-geocentric theory. Another observation used in favor of the geocentric model at the time was the apparent consistency of Venus' luminosity, which implies that it is usually about the same distance from Earth, which in turn is more consistent with geocentrism than heliocentrism. In reality, that is because the loss of light caused by Venus' phases compensates for the increase in apparent size caused by its varying distance from Earth. Objections to heliocentrism utilized the natural tendency of terrestrial bodies to come to rest as near as possible to the center of the earth, and barring the opportunity to fall closer the center, not to move unless forced by an outside object, or transformed to a different element by heat or moisture. |

|||

Atmospheric explanations for many phenomena were preferred because the Eudoxan–Aristotelian model based on perfectly concentric spheres was not intended to explain changes in the brightness of the planets due to a change in distance.<ref name= "Hetherington2006"/> Eventually, perfectly concentric spheres were abandoned as it wasn't possible to develop a sufficiently accurate model under that ideal. However, while providing for similar explanations, the later [[deferent and epicycle]] model proved to be flexible enough to accommodate observations for many centuries. |

|||

== Ptolemaic Model ==<!-- This section is linked from [[Giordano Bruno]] --> |

|||

Although the basic tenets of Greek geocentrism were established by the time of Aristotle, the details of his system did not become standard. The '''Ptolemaic system''', espoused by the [[Hellenization|Hellenistic]] astronomer [[Ptolemy|Claudius Ptolemaeus]] in the 2nd century AD finally accomplished this process. His main astronomical work, the ''[[Almagest]]'', was the culmination of centuries of work by [[Ancient Greece|Hellenic]], [[Hellenistic civilization|Hellenistic]] and [[Babylonian astronomy|Babylonian]] astronomers; it was accepted for over a millennium as the correct cosmological model by European and [[Islamic astronomy|Islamic astronomers]]. Because of its influence, the Ptolemaic system is sometimes considered identical with the '''geocentric model'''. |

|||

Ptolemy argued that the Earth was in the center of the universe, from the simple observation that half the stars were above the horizon and half were below the horizon at any time (stars on rotating stellar sphere), and the assumption that the stars were all at some modest distance from the center of the universe. If the Earth was substantially displaced from the center, this division into visible and invisible stars would not be equal.{{refn|group=n|This argument is given in Book I, Chapter 5, of the ''Almagest''.<ref>{{harvnb|Crowe|1990|pp=60–2}}</ref>}} |

|||

= |

|||

<!--=== Geocentrism and Islamic astronomy === |

|||

{{Main|Maragheh observatory|Astronomy in medieval Islam|Islamic cosmology}} |

|||

Due to the scientific dominance of the [[Ptolemaic model|Ptolemaic system]] in [[Astronomy in medieval Islam|Islamic astronomy]], the [[List of Muslim astronomers|Muslim astronomers]] accepted unanimously the geocentric model.<!-- please don't dilute the summary, because that is what the quote says − every single medieval Muslim authority on the matter -->{{refn|group=n|"All Islamic astronomers from Thabit ibn Qurra in the ninth century to Ibn al-Shatir in the fourteenth, and all natural philosophers from al-Kindi to Averroes and later, are known to have accepted ... the Greek picture of the world as consisting of two spheres of which one, the celestial sphere ... concentrically envelops the other."<ref>{{cite journal |first= A. I. |last= Sabra |title= Configuring the universe: Aporetic, problem solving, and kinematic modeling as themes of Arabic astronomy |journal= Perspectives on Science |volume= 6 |issue= 3 |year= 1998 |pages= 317–8}}</ref>}} |

|||

In the 12th century, [[Abū Ishāq Ibrāhīm al-Zarqālī|Arzachel]] departed from the ancient Greek idea of [[uniform circular motion]]s by hypothesizing that the planet [[Mercury (planet)|Mercury]] moves in an [[elliptic orbit]],<ref name= "Rufus1939"/><ref name= "Hartner1955"/> while [[Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji|Alpetragius]] proposed a planetary model that abandoned the [[equant]], [[Deferent and epicycle|epicycle and eccentric]] mechanisms,<ref name= "Goldstein1972"/> though this resulted in a system that was mathematically less accurate.<ref name= "Gale"/> [[Fakhr al-Din al-Razi]] (1149–1209), in dealing with his [[Physics in medieval Islam|conception of physics]] and the physical world in his ''Matalib'', rejects the [[Aristotelianism|Aristotelian]] and [[Avicennism|Avicennian]] notion of the Earth's centrality within the universe, but instead argues that there are "a thousand thousand worlds (''alfa alfi 'awalim'') beyond this world such that each one of those worlds be bigger and more massive than this world as well as having the like of what this world has." To support his [[Islamic theology|theological argument]], he cites the [[Qur'an]]ic verse, "All praise belongs to God, Lord of the Worlds," emphasizing the term "Worlds."<ref name= "Setia2004"/> |

|||

The "Maragha Revolution" refers to the Maragha school's revolution against Ptolemaic astronomy. The "Maragha school" was an astronomical tradition beginning in the [[Maragheh observatory|Maragha observatory]] and continuing with astronomers from the [[Umayyad Mosque|Damascus mosque]] and [[Ulugh Beg Observatory|Samarkand observatory]]. Like their [[Al-Andalus|Andalusian]] predecessors, the Maragha astronomers attempted to solve the [[equant]] problem (the circle around whose circumference a planet or the center of an [[epicycle]] was conceived to move uniformly) and produce alternative configurations to the Ptolemaic model without abandoning geocentrism. They were more successful than their Andalusian predecessors in producing non-Ptolemaic configurations which eliminated the equant and eccentrics, were more accurate than the Ptolemaic model in numerically predicting planetary positions, and were in better agreement with empirical observations.<ref name= "Saliba1994"/> The most important of the Maragha astronomers included [[Mo'ayyeduddin Urdi]] (d. 1266), [[Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī]] (1201–1274), [[Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi]] (1236–1311), [[Ibn al-Shatir]] (1304–1375), [[Ali Qushji]] (c. 1474), [[Al-Birjandi]] (d. 1525), and Shams al-Din al-Khafri (d. 1550).<ref name= "Dallal1999"/> [[Ibn al-Shatir]], the Damascene astronomer (1304–1375 AD) working at the [[Umayyad Mosque]], wrote a major book entitled ''Kitab Nihayat al-Sul fi Tashih al-Usul'' (''A Final Inquiry Concerning the Rectification of Planetary Theory'') on a theory which departs largely from the Ptolemaic system known at that time. In his book, "Ibn al-Shatir, an Arab astronomer of the fourteenth century," E. S. Kennedy wrote "what is of most interest, however, is that Ibn al-Shatir's lunar theory, except for trivial differences in parameters, is identical with that of [[Nicolaus Copernicus|Copernicus]] (1473–1543 AD)." The discovery that the models of Ibn al-Shatir are mathematically identical to those of Copernicus suggests the possible transmission of these models to Europe.<ref name= "Guessoun2008"/> At the Maragha and [[Ulugh Beg Observatory|Samarkand observatories]], the [[Earth's rotation]] was discussed by al-Tusi and [[Ali Qushji]] (b. 1403); the arguments and evidence they used resemble those used by Copernicus to support the Earth's motion.<ref name= "Ragep2001a"/><ref name= "Ragep2001b"/> |

|||

However, the Maragha school never made the [[paradigm shift]] to heliocentrism.<ref name="Huff2003"/> The influence of the Maragha school on [[Copernicus]] remains speculative, since there is no documentary evidence to prove it. The possibility that Copernicus independently developed the Tusi couple remains open, since no researcher has yet demonstrated that he knew about Tusi's work or that of the Maragha school.<ref name="Huff2003" /><ref name="KirmaniSingh2005"/> |

|||

== Geocentrism and rival systems == |

|||

[[File:Geocentrism.jpg|right|thumb|This drawing from an [[Iceland]]ic manuscript dated around 1750 illustrates the geocentric model.]] |

|||

Not all Greeks agreed with the geocentric model. The [[Pythagoreanism|Pythagorean]] system has already been mentioned; some Pythagoreans believed the Earth to be one of several planets going around a central fire.<ref name= "JohansenRosenmeier1998"/> [[Hicetas]] and [[Ecphantus]], two Pythagoreans of the 5th century BC, and [[Heraclides Ponticus]] in the 4th century BC, believed that the Earth rotated on its axis but remained at the center of the universe.<ref name= "Sarton1953"/> Such a system still qualifies as geocentric. It was revived in the [[Middle Ages]] by [[Jean Buridan]]. Heraclides Ponticus was once thought to have proposed that both Venus and Mercury went around the Sun rather than the Earth, but this is no longer accepted.<ref name= "Eastwood1992"/> [[Martianus Capella]] definitely put Mercury and Venus in orbit around the Sun.<ref name="Lindberg2010"/> [[Aristarchus of Samos]] was the most radical. He wrote a work, which has not survived, on [[heliocentrism]], saying that the Sun was at the center of the universe, while the Earth and other planets revolved around it.<ref>{{harvnb|Lawson|2004|page= 19}}</ref> His theory was not popular, and he had one named follower, [[Seleucus of Seleucia]].<ref name= "Russell1945"/> |

|||

=== Copernican system === |

|||

{{Main|Copernican heliocentrism}} |

|||

In 1543, the geocentric system met its first serious challenge with the publication of [[Copernicus|Copernicus']] ''[[De revolutionibus orbium coelestium]]'' (''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres''), which posited that the Earth and the other planets instead revolved around the Sun. The geocentric system was still held for many years afterwards, as at the time the Copernican system did not offer better predictions than the geocentric system, and it posed problems for both [[natural philosophy]] and scripture. The Copernican system was no more accurate than Ptolemy's system, because it still used circular orbits. This was not altered until [[Johannes Kepler]] postulated that they were elliptical (Kepler's [[Kepler's laws of planetary motion#First Law|first law of planetary motion]]). |

|||

With the invention of the [[telescope]] in 1609, observations made by [[Galileo Galilei]] (such as that [[Jupiter]] has moons) called into question some of the tenets of geocentrism but did not seriously threaten it. Because he observed dark "spots" on the moon, craters, he remarked that the moon was not a perfect celestial body as had been previously conceived. This was the first time someone could see imperfections on a celestial body that was supposed to be composed of perfect [[aether (classical element)|aether]]. As such, because the moon's imperfections could now be related to those seen on Earth, one could argue that neither was unique: rather, they were both just celestial bodies made from earthlike material. Galileo could also see the moons of Jupiter, which he dedicated to [[Cosimo II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany|Cosimo II de' Medici]], and stated that they orbited around Jupiter, not Earth.<ref name= "Finocchiaro2008"/> This was a significant claim because if true, it would mean that not everything revolved around Earth, shattering previously held theological and scientific belief. As such, Galileo's theories challenging the geocentrism of our universe were silenced by the Church and general skepticism towards any system that did not place Earth at its center, preserving the thoughts and systems of Ptolemy and Aristotle. |

|||

[[File:Phases-of-Venus.svg|thumb|Phases of Venus]] |

|||

In December 1610, [[Galileo Galilei]] used his telescope to observe that [[Venus]] showed all [[Phases of Venus|phase]]s, just [[lunar phase|like the Moon]]. He thought that while this observation was incompatible with the Ptolemaic system, it was a natural consequence of the heliocentric system. |

|||

However, Ptolemy placed Venus' [[deferent]] and [[epicycle]] entirely inside the sphere of the Sun (between the Sun and Mercury), but this was arbitrary; he could just as easily have swapped Venus and Mercury and put them on the other side of the Sun, or made any other arrangement of Venus and Mercury, as long as they were always near a line running from the Earth through the Sun, such as placing the center of the Venus epicycle near the Sun. In this case, if the Sun is the source of all the light, under the Ptolemaic system: |

|||

{{quote|If Venus is between Earth and the Sun, the phase of Venus must always be [[crescent]] or all dark. |

|||

If Venus is beyond the Sun, the phase of Venus must always be [[gibbous]] or full.}} |

|||

But Galileo saw Venus at first small and full, and later large and crescent. |

|||

This showed that with a Ptolemaic cosmology, the Venus epicycle can be neither completely inside nor completely outside of the orbit of the Sun. As a result, Ptolemaics abandoned the idea that the epicycle of Venus was completely inside the Sun, and later 17th century competition between astronomical cosmologies focused on variations of [[Tycho Brahe|Tycho Brahe's]] [[Tychonic system]] (in which the Earth was still at the center of the universe, and around it revolved the Sun, but all other planets revolved around the Sun in one massive set of epicycles), or variations on the Copernican system. |

|||

== Gravitation == |

|||

[[Johannes Kepler]], after analysing [[Tycho Brahe]]'s famously accurate observations, constructed his [[Kepler's laws of planetary motion|three laws]] in 1609 and 1619, based on a heliocentric view where the planets move in [[elliptical]] paths. Using these laws, he was the first astronomer to successfully predict a [[Astronomical transit|transit]] of Venus (for the year 1631). The transition from circular orbits to elliptical planetary paths dramatically changed the accuracy of celestial observations and predictions. Because the heliocentric model by Copernicus was no more accurate than Ptolemy's system, new mathematical observations were needed to persuade those who still held on to the geocentric model. However, the observations made by Kepler, using Brahe's data, became a problem not easily overturned for geocentrists. |

|||

In 1687, [[Isaac Newton]] devised his [[law of universal gravitation]], which introduced gravitation as the force that both kept the Earth and planets moving through the heavens and also kept the air from flying away, allowing scientists to quickly construct a plausible heliocentric model for the solar system. In his ''[[Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica|Principia]]'', Newton explained his system of how gravity, previously considered to be an occult force, conducted the movements of celestial bodies, and kept our solar system in its working order. His descriptions of centripetal force<ref name= "Densmore2004"/> were a breakthrough in scientific thought which used the newly developed [[differential calculus]], and finally replaced the previous schools of scientific thought, i.e. those of Aristotle and Ptolemy. However, the process was gradual. |

|||

In 1838, astronomer [[Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel]] successfully measured the [[parallax]] of the star [[61 Cygni]], disproving Ptolemy's assertion that parallax motion did not exist. This finally substantiated the suppositions made by Copernicus with accurate, dependable scientific observations, and displayed truly how far away stars were from Earth. |

|||

A geocentric frame is useful for many everyday activities and most laboratory experiments, but is a less appropriate choice for solar-system mechanics and space travel. While a [[Heliocentrism|heliocentric frame]] is most useful in those cases, galactic and extra-galactic astronomy is easier if the sun is treated as neither stationary nor the center of the universe, but rotating around the center of our galaxy, and in turn our galaxy is also not at rest in the [[Cosmic Microwave Background#Velocity relative to CMB anisotropy|cosmic background]]. |

|||

== Religious and contemporary adherence to geocentrism== |

|||

[[File:Orlando-Ferguson-flat-earth-map edit.jpg|right|thumb|300px|''Map of the Square and Stationary Earth'', by Orlando Ferguson (1893)]] |

|||