Geosentrisme: Perbedaan antara revisi

JohnThorne (bicara | kontrib) Tidak ada ringkasan suntingan |

JohnThorne (bicara | kontrib) Tidak ada ringkasan suntingan |

||

| Baris 75: | Baris 75: | ||

In 1543, the geocentric system met its first serious challenge with the publication of [[Copernicus|Copernicus']] ''[[De revolutionibus orbium coelestium]]'' (''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres''), which posited that the Earth and the other planets instead revolved around the Sun. The geocentric system was still held for many years afterwards, as at the time the Copernican system did not offer better predictions than the geocentric system, and it posed problems for both [[natural philosophy]] and scripture. The Copernican system was no more accurate than Ptolemy's system, because it still used circular orbits. This was not altered until [[Johannes Kepler]] postulated that they were elliptical (Kepler's [[Kepler's laws of planetary motion#First Law|first law of planetary motion]]). |

In 1543, the geocentric system met its first serious challenge with the publication of [[Copernicus|Copernicus']] ''[[De revolutionibus orbium coelestium]]'' (''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres''), which posited that the Earth and the other planets instead revolved around the Sun. The geocentric system was still held for many years afterwards, as at the time the Copernican system did not offer better predictions than the geocentric system, and it posed problems for both [[natural philosophy]] and scripture. The Copernican system was no more accurate than Ptolemy's system, because it still used circular orbits. This was not altered until [[Johannes Kepler]] postulated that they were elliptical (Kepler's [[Kepler's laws of planetary motion#First Law|first law of planetary motion]]). |

||

With the invention of the [[telescope]] in 1609, observations made by [[Galileo Galilei]] (such as that [[Jupiter]] has moons) called into question some of the tenets of geocentrism but did not seriously threaten it. Because he observed dark "spots" on the moon, craters, he remarked that the moon was not a perfect celestial body as had been previously conceived. This was the first time someone could see imperfections on a celestial body that was supposed to be composed of perfect [[aether (classical element)|aether]]. As such, because the moon's imperfections could now be related to those seen on Earth, one could argue that neither was unique: rather, they were both just celestial bodies made from earthlike material. Galileo could also see the moons of Jupiter, which he dedicated to [[Cosimo II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany|Cosimo II de' Medici]], and stated that they orbited around Jupiter, not Earth.<ref name= |

With the invention of the [[telescope]] in 1609, observations made by [[Galileo Galilei]] (such as that [[Jupiter]] has moons) called into question some of the tenets of geocentrism but did not seriously threaten it. Because he observed dark "spots" on the moon, craters, he remarked that the moon was not a perfect celestial body as had been previously conceived. This was the first time someone could see imperfections on a celestial body that was supposed to be composed of perfect [[aether (classical element)|aether]]. As such, because the moon's imperfections could now be related to those seen on Earth, one could argue that neither was unique: rather, they were both just celestial bodies made from earthlike material. Galileo could also see the moons of Jupiter, which he dedicated to [[Cosimo II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany|Cosimo II de' Medici]], and stated that they orbited around Jupiter, not Earth.<ref name="Finocchiaro1989">{{cite book |title= The Galileo Affair: A Documentary History |first= Maurice A. |last= Finocchiaro |location= Berkeley |publisher= University of California Press |year= 1989 |page= [http://books.google.com/books?id=k7D1CXFBl2gC&pg=PA307 307] |isbn= 9780520066625}}</ref> This was a significant claim because if true, it would mean that not everything revolved around Earth, shattering previously held theological and scientific belief. As such, Galileo's theories challenging the geocentrism of our universe were silenced by the Church and general skepticism towards any system that did not place Earth at its center, preserving the thoughts and systems of Ptolemy and Aristotle. |

||

[[File:Phases-of-Venus.svg|thumb|Phases of Venus]] |

[[File:Phases-of-Venus.svg|thumb|Phases of Venus]] |

||

| Baris 106: | Baris 106: | ||

{{quote|After all, Copernicanism was the first major victory of science over religion, so it's inevitable that some folks would think that everything that's wrong with the world began there. (Steven Dutch of the [[University of Wisconsin–Madison]] <ref>[http://www.uwgb.edu/dutchs/PSEUDOSC/Geocentrism.HTM Geocentrism lives]</ref>}} |

{{quote|After all, Copernicanism was the first major victory of science over religion, so it's inevitable that some folks would think that everything that's wrong with the world began there. (Steven Dutch of the [[University of Wisconsin–Madison]] <ref>[http://www.uwgb.edu/dutchs/PSEUDOSC/Geocentrism.HTM Geocentrism lives]</ref>}} |

||

[[Morris Berman]] quotes survey results that show currently some 20% of the U.S. population believe that the sun goes around the Earth (geocentricism) rather than the Earth goes around the sun (heliocentricism), while a further 9% claimed not to know.<ref name= "Berman2006"/> Polls conducted by [[The Gallup Organization|Gallup]] in the 1990s found that 16% of Germans, 18% of Americans and 19% of Britons hold that the Sun revolves around the Earth.<ref name= "Crabtree1999"/> A study conducted in 2005 by Jon D. Miller of [[Northwestern University]], an expert in the public understanding of science and technology,<ref name= "MillerBio"/> found that about 20%, or one in five, of American adults believe that the Sun orbits the Earth.<ref name= "Dean2005"/> According to 2011 [[VTSIOM]] poll, 32% of [[Russians]] believe that the Sun orbits the Earth.<ref name= "RussianStudy2011"/> |

[[Morris Berman]] quotes survey results that show currently some 20% of the U.S. population believe that the sun goes around the Earth (geocentricism) rather than the Earth goes around the sun (heliocentricism), while a further 9% claimed not to know.<ref name= "Berman2006"/> Polls conducted by [[The Gallup Organization|Gallup]] in the 1990s found that 16% of Germans, 18% of Americans and 19% of Britons hold that the Sun revolves around the Earth.<ref name= "Crabtree1999"/> A study conducted in 2005 by Jon D. Miller of [[Northwestern University]], an expert in the public understanding of science and technology,<ref name= "MillerBio"/> found that about 20%, or one in five, of American adults believe that the Sun orbits the Earth.<ref name= "Dean2005"/> According to 2011 [[VTSIOM]] poll, 32% of [[Russians]] believe that the Sun orbits the Earth.<ref name= "RussianStudy2011">{{citation |url= http://wciom.ru/index.php?id=459&uid=111345 |title= 'СОЛНЦЕ - СПУТНИК ЗЕМЛИ', ИЛИ РЕЙТИНГ НАУЧНЫХ ЗАБЛУЖДЕНИЙ РОССИЯН |trans_title= 'Sun-earth', or rating scientific fallacies of Russians |issue= Пресс-выпуск №1684 <nowiki>[</nowiki>Press release no. 1684<nowiki>]</nowiki> |date= 2011-02-08 |language= ru |publisher= ВЦИОМ <nowiki>[</nowiki>[[VTSIOM|All-Russian Center for the Study of Public Opinion]]<nowiki>]</nowiki> |postscript= .}}</ref> |

||

=== Posisi historis hierarki Katolik Roma === |

=== Posisi historis hierarki Katolik Roma === |

||

| Baris 117: | Baris 117: | ||

:The first and greatest care of Leo XIII was to set forth the teaching on the truth of the Sacred Books and to defend it from attack. Hence with grave words did he proclaim that there is no error whatsoever if the sacred writer, speaking of things of the physical order "went by what sensibly appeared" as the Angelic Doctor says,[5] speaking either "in figurative language, or in terms which were commonly used at the time, and which in many instances are in daily use at this day, even among the most eminent men of science." For "the sacred writers, or to speak more accurately – the words are St. Augustine's – [6] the Holy Spirit, Who spoke by them, did not intend to teach men these things – that is the essential nature of the things of the universe – things in no way profitable to salvation"; which principle "will apply to cognate sciences, and especially to history,"[7] that is, by refuting, "in a somewhat similar way the fallacies of the adversaries and defending the historical truth of Sacred Scripture from their attacks ([[Divino Afflante Spiritu]] 3). |

:The first and greatest care of Leo XIII was to set forth the teaching on the truth of the Sacred Books and to defend it from attack. Hence with grave words did he proclaim that there is no error whatsoever if the sacred writer, speaking of things of the physical order "went by what sensibly appeared" as the Angelic Doctor says,[5] speaking either "in figurative language, or in terms which were commonly used at the time, and which in many instances are in daily use at this day, even among the most eminent men of science." For "the sacred writers, or to speak more accurately – the words are St. Augustine's – [6] the Holy Spirit, Who spoke by them, did not intend to teach men these things – that is the essential nature of the things of the universe – things in no way profitable to salvation"; which principle "will apply to cognate sciences, and especially to history,"[7] that is, by refuting, "in a somewhat similar way the fallacies of the adversaries and defending the historical truth of Sacred Scripture from their attacks ([[Divino Afflante Spiritu]] 3). |

||

In 1664 [[Alexander VII]] republished the ''[[Index Librorum Prohibitorum]]'' (''List of Prohibited Books'') and attached the various decrees connected with those books, including those concerned with heliocentrism. He stated in a [[Papal Bull]] that his purpose in doing so was that "the succession of things done from the beginning might be made known [''quo rei ab initio gestae series innotescat'']."<ref name= "Alexandri VII1664"/> |

In 1664 [[Alexander VII]] republished the ''[[Index Librorum Prohibitorum]]'' (''List of Prohibited Books'') and attached the various decrees connected with those books, including those concerned with heliocentrism. He stated in a [[Papal Bull]] that his purpose in doing so was that "the succession of things done from the beginning might be made known [''quo rei ab initio gestae series innotescat'']."<ref name= "Alexandri VII1664">{{cite book |title= Index librorum prohibitorum Alexandri VII |url= http://books.google.com/books?id=PSVCAAAAcAAJ |year= 1664 |publisher= Ex typographia Reurendae Camerae Apostolicae |location= Rome |language= Latin |page= v}}</ref> |

||

The position of the curia evolved slowly over the centuries towards permitting the heliocentric view. In 1757, during the papacy of Benedict XIV, the Congregation of the Index withdrew the decree which prohibited ''all'' books teaching the earth's motion, although the ''Dialogue'' and a few other books continued to be explicitly included. In 1820, the Congregation of the Holy Office, with the pope's approval, decreed that Catholic astronomer [[Joseph Settele]] was allowed to treat the earth's motion as an established fact. In 1822, the Congregation of the Holy Office removed the prohibition on the publication of books treating of the earth's motion in accordance with modern astronomy and Pope Pius VII ratified the decision. The 1835 edition of the Catholic Index of Prohibited Books for the first time omits the ''Dialogue'' from the list.<ref name="Finocchiaro1989"/> In a [[papal encyclical]] written in 1921 [[Pope Benedict XV]] stated that, "though this earth on which we live may not be the center of the universe as at one time was thought, it was the scene of the original happiness of our first ancestors, witness of their unhappy fall, as too of the Redemption of mankind through the Passion and Death of Jesus Christ."<ref name= "BenedictXV1921"/> In 1965 the [[Second Vatican Council]] stated that, "Consequently, we cannot but deplore certain habits of mind, which are sometimes found too among Christians, which do not sufficiently attend to the rightful independence of science and which, from the arguments and controversies they spark, lead many minds to conclude that faith and science are mutually opposed."<ref name= "PaulIV19665"/> The footnote on this statement is to Msgr. Pio Paschini's, ''Vita e opere di Galileo Galilei'', 2 volumes, Vatican Press (1964). And [[Pope John Paul II]] regretted the treatment which Galileo received, in a speech to the [[Pontifical Academy of Sciences]] in 1992. The Pope declared the incident to be based on a "tragic mutual miscomprehension". He further stated: |

The position of the curia evolved slowly over the centuries towards permitting the heliocentric view. In 1757, during the papacy of Benedict XIV, the Congregation of the Index withdrew the decree which prohibited ''all'' books teaching the earth's motion, although the ''Dialogue'' and a few other books continued to be explicitly included. In 1820, the Congregation of the Holy Office, with the pope's approval, decreed that Catholic astronomer [[Joseph Settele]] was allowed to treat the earth's motion as an established fact. In 1822, the Congregation of the Holy Office removed the prohibition on the publication of books treating of the earth's motion in accordance with modern astronomy and Pope Pius VII ratified the decision. The 1835 edition of the Catholic Index of Prohibited Books for the first time omits the ''Dialogue'' from the list.<ref name="Finocchiaro1989"/> In a [[papal encyclical]] written in 1921 [[Pope Benedict XV]] stated that, "though this earth on which we live may not be the center of the universe as at one time was thought, it was the scene of the original happiness of our first ancestors, witness of their unhappy fall, as too of the Redemption of mankind through the Passion and Death of Jesus Christ."<ref name= "BenedictXV1921">{{cite web |url= http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xv/encyclicals/documents/hf_ben-xv_enc_30041921_in-praeclara-summorum_en.html |title= In Praeclara Summorum: Encyclical of Pope Benedict XV on Dante to Professors and Students of Literature and Learning in the Catholic World |date= 1921-04-30 |location= Rome |page= § 4 |nopp=y}}</ref> In 1965 the [[Second Vatican Council]] stated that, "Consequently, we cannot but deplore certain habits of mind, which are sometimes found too among Christians, which do not sufficiently attend to the rightful independence of science and which, from the arguments and controversies they spark, lead many minds to conclude that faith and science are mutually opposed."<ref name= "PaulIV19665">{{cite web |url= http://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_cons_19651207_gaudium-et-spes_en.html |title= Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World 'Gaudium Et Spes' Promulgated by His Holiness, Pope Paul IV on December 7, 1965 |page= § 36 |nopp=y}}</ref> The footnote on this statement is to Msgr. Pio Paschini's, ''Vita e opere di Galileo Galilei'', 2 volumes, Vatican Press (1964). And [[Pope John Paul II]] regretted the treatment which Galileo received, in a speech to the [[Pontifical Academy of Sciences]] in 1992. The Pope declared the incident to be based on a "tragic mutual miscomprehension". He further stated: |

||

:Cardinal Poupard has also reminded us that the sentence of 1633 was not irreformable, and that the debate which had not ceased to evolve thereafter, was closed in 1820 with the imprimatur given to the work of Canon Settele. . . . The error of the theologians of the time, when they maintained the centrality of the earth, was to think that our understanding of the physical world's structure was, in some way, imposed by the literal sense of Sacred Scripture. Let us recall the celebrated saying attributed to Baronius "Spiritui Sancto mentem fuisse nos docere quomodo ad coelum eatur, non quomodo coelum gradiatur". In fact, the Bible does not concern itself with the details of the physical world, the understanding of which is the competence of human experience and reasoning. There exist two realms of knowledge, one which has its source in Revelation and one which reason can discover by its own power. To the latter belong especially the experimental sciences and philosophy. The distinction between the two realms of knowledge ought not to be understood as opposition.<ref name= "John PaulII1992"/> |

:Cardinal Poupard has also reminded us that the sentence of 1633 was not irreformable, and that the debate which had not ceased to evolve thereafter, was closed in 1820 with the imprimatur given to the work of Canon Settele. . . . The error of the theologians of the time, when they maintained the centrality of the earth, was to think that our understanding of the physical world's structure was, in some way, imposed by the literal sense of Sacred Scripture. Let us recall the celebrated saying attributed to Baronius "Spiritui Sancto mentem fuisse nos docere quomodo ad coelum eatur, non quomodo coelum gradiatur". In fact, the Bible does not concern itself with the details of the physical world, the understanding of which is the competence of human experience and reasoning. There exist two realms of knowledge, one which has its source in Revelation and one which reason can discover by its own power. To the latter belong especially the experimental sciences and philosophy. The distinction between the two realms of knowledge ought not to be understood as opposition.<ref name= "John PaulII1992">{{cite journal |title= Faith can never conflict with reason |url= http://www.its.caltech.edu/~nmcenter/sci-cp/sci-9211.html |journal= L'Osservatore Romano |volume= 44 |issue= 1264 |date= 1992-11-04 |author= Pope John Paul II}} (Published English translation).</ref> |

||

--> |

--> |

||

=== Yudaisme Ortodoks === |

=== Yudaisme Ortodoks === |

||

| Baris 185: | Baris 185: | ||

<ref name= "MillerBio">{{cite web |url= http://www.cmb.northwestern.edu/faculty/jon_miller.htm |title= Jon D. Miller |work= Northwestern University website |accessdate= 2007-07-19}}</ref> |

<ref name= "MillerBio">{{cite web |url= http://www.cmb.northwestern.edu/faculty/jon_miller.htm |title= Jon D. Miller |work= Northwestern University website |accessdate= 2007-07-19}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "Dean2005">{{cite news |url= http://www.nytimes.com/2005/08/30/science/30profile.html?ex=1184990400&en=2fb126c3132f89ae&ei=5070 |title=Scientific savvy? In U.S., not much |first= Cornelia |last= Dean |date= 2005-08-30 |newspaper= New York Times |accessdate= 2007-07-19}}</ref> |

<ref name= "Dean2005">{{cite news |url= http://www.nytimes.com/2005/08/30/science/30profile.html?ex=1184990400&en=2fb126c3132f89ae&ei=5070 |title=Scientific savvy? In U.S., not much |first= Cornelia |last= Dean |date= 2005-08-30 |newspaper= New York Times |accessdate= 2007-07-19}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "RussianStudy2011">{{citation |url= http://wciom.ru/index.php?id=459&uid=111345 |title= 'СОЛНЦЕ - СПУТНИК ЗЕМЛИ', ИЛИ РЕЙТИНГ НАУЧНЫХ ЗАБЛУЖДЕНИЙ РОССИЯН |trans_title= 'Sun-earth', or rating scientific fallacies of Russians |issue= Пресс-выпуск №1684 <nowiki>[</nowiki>Press release no. 1684<nowiki>]</nowiki> |date= 2011-02-08 |language= ru |publisher= ВЦИОМ <nowiki>[</nowiki>[[VTSIOM|All-Russian Center for the Study of Public Opinion]]<nowiki>]</nowiki> |postscript= .}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Finocchiaro1989">{{cite book |title= The Galileo Affair: A Documentary History |first= Maurice A. |last= Finocchiaro |location= Berkeley |publisher= University of California Press |year= 1989 |page= [http://books.google.com/books?id=k7D1CXFBl2gC&pg=PA307 307] |isbn= 9780520066625}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Alexandri VII1664">{{cite book |title= Index librorum prohibitorum Alexandri VII |url= http://books.google.com/books?id=PSVCAAAAcAAJ |year= 1664 |publisher= Ex typographia Reurendae Camerae Apostolicae |location= Rome |language= Latin |page= v}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "BenedictXV1921">{{cite web |url= http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xv/encyclicals/documents/hf_ben-xv_enc_30041921_in-praeclara-summorum_en.html |title= In Praeclara Summorum: Encyclical of Pope Benedict XV on Dante to Professors and Students of Literature and Learning in the Catholic World |date= 1921-04-30 |location= Rome |page= § 4 |nopp=y}}</ref> |

|||

<!-- |

|||

<ref name= "PaulIV19665">{{cite web |url= http://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_cons_19651207_gaudium-et-spes_en.html |title= Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World 'Gaudium Et Spes' Promulgated by His Holiness, Pope Paul IV on December 7, 1965 |page= § 36 |nopp=y}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "John PaulII1992">{{cite journal |title= Faith can never conflict with reason |url= http://www.its.caltech.edu/~nmcenter/sci-cp/sci-9211.html |journal= L'Osservatore Romano |volume= 44 |issue= 1264 |date= 1992-11-04 |author= Pope John Paul II}} (Published English translation).</ref>--> |

|||

<ref name="Nussbaum2007">{{Cite journal |url= http://www.skeptic.com/the_magazine/featured_articles/v12n03_orthodox_judaism_and_evolution.html |title= Orthodox Jews & science: An empirical study of their attitudes toward evolution, the fossil record, and modern geology |accessdate= 2008-12-18 |last= Nussbaum |first= Alexander |date= 2007-12-19 |journal= Skeptic Magazine}}</ref> |

<ref name="Nussbaum2007">{{Cite journal |url= http://www.skeptic.com/the_magazine/featured_articles/v12n03_orthodox_judaism_and_evolution.html |title= Orthodox Jews & science: An empirical study of their attitudes toward evolution, the fossil record, and modern geology |accessdate= 2008-12-18 |last= Nussbaum |first= Alexander |date= 2007-12-19 |journal= Skeptic Magazine}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "Nussbaum2002">{{cite journal |first= Alexander |last= Nussbaum |title= Creationism and geocentrism among Orthodox Jewish scientists |journal= Reports of the National Center for Science Education |date=January–April 2002 |pages= 38–43}}</ref> |

<ref name= "Nussbaum2002">{{cite journal |first= Alexander |last= Nussbaum |title= Creationism and geocentrism among Orthodox Jewish scientists |journal= Reports of the National Center for Science Education |date=January–April 2002 |pages= 38–43}}</ref> |

||

Revisi per 3 Maret 2014 17.34

Geosentrisme atau disebut Teori Geosentrik, Model Geosentrik (bahasa Inggris: geocentric model atau geocentrism, Ptolemaic system) adalah istilah astronomi yang menggambarkan alam semesta dengan bumi sebagai pusatnya dan pusat pergerakan semua benda-benda langit. Model ini menjadi sistem kosmologi predominan pada budaya kuno misalnya Yunani kuno, yang meliputi sistem-sistem terkenal yang dikemukakan oleh Aristoteles and Claudius Ptolemaeus.[1]

Dua pengamatan umum mendukung pandangan bahwa Bumi adalah pusat dari alam semesta. Pengamatan pertama adalah bintang-bintang, matahari dan planet-planet nampak berputar mengitari bumi setiap hari, membuat bumi adalah pusat sistem ini. Lebih lanjut, setiap bintang berada pada suatu bulatan stelar atau selestial ("stellar sphere" atau "celestial sphere"), di mana bumi adalah pusatnya, yang berkeliling setiap hari, di seputar garis yang menghubungkan kutub utara dan selatan sebagai aksisnya. Bintang-bintang yang terdekat dengan khatulistiwa nampak naik dan turun paling jauh, tetapi setiap bintang kembali ke titik terbitnya setiap hari.[2] Observasi umum kedua yang mendukung model geosentrik adalah bumi nampaknya tidak bergerak dari sudut pandang pengamat yang berada di bumi, bahwa bumi itu solid, stabil dan tetap di tempat. Dengan kata lain, benar-benar dalam posisi diam.

Model geosentrik biasanya dikombinasi dengan suatu Bumi yang bulat oleh filsuf Romawi kuno dan abad pertengahan. Ini tidak sama dengan pandangan model Bumi datar yang disiratkan dalam sejumlah mitologi, sebagaimana juga dalah kosmologi kitab-kitab suci dan Latin kuno.[n 1][n 2][n 3]

Yunani kuno

Teori atau model Geosentrik memasuki astronomi dan filsafat Yunani sejak dini; dapat ditelusuri pada peninggalan filsafat sebelum zaman Sokrates. Pada abad ke-6 SM, Anaximander mengemukakan suatu kosmologi dengan bumi berbentuk seperti potongan suatu tiang (sebuah tabung), berada di awang-awang di pusat segala sesuatu. Matahari, Bulan, and planet-planet adalah lubang-lubang dalam roda-roda yang tidak kelihatan yang mengelilingi bumi; melalui lubang-lubang ini manusia dapat melihat api yang tersembunyi. Pada waktu yang sama, para pengikut Pythagoras, yang disebut kelompok Pythagorean, berpendapat bahwa bumi adalah suatu bola (menurut pengamatan gerhana-gerhana), tetapi bukan sebagai pusat, melainkan bergerak mengelilingi suatu api yang tidak nampak. Kemudian pandangan-pandangan ini digabungkan, sehingga kalangan terpelajar Yunani sejak dari abad ke-4 SM berpikir bahwa bumi adalah bola yang menjadi pusat alam semesta.[6]

Model Ptolemaik

Meskipun prinsip dasar geosentrisme Yunani sudah tersusun pada zaman Aristoteles, detail sistem ini belum menjadi standar. Sistem Ptolemaik, yang diutarakan oleh astronomer Helenistik Mesir Claudius Ptolemaeus pada abad ke- 2 M akhirnya berhasil menjadi standar. Karya astronomi utamanya, Almagest, merupakan puncak karya-karya selama berabad-abad-abad oleh para astronom Yunani kuno, Helenistik dan Babilonia; karya itu diterima selama lebih dari satu milenium sebagai model kosmologi yang benar oleh para astronom Eropa dan Islam. Karena begitu kuat pengaruhnya, sistem Ptolemaik kadang kala dianggap sama dengan model geosentrik.

Ptolemy berpendapat bahwa bumi adalah pusat alam semesta berdasarkan pengamatan sederhana yaitu setengah jumlah bintang-bintang terletak di atas horizon dan setengahnya di bawah horizon pada waktu manapun (bintang-bintang pada bulatan orbitnya), dan anggapan bahwa bintang–bintang semuanya terletak pada suatu jarak tertentu dari pusat semesta. Jika bumi terletak cukup jauh dari pusat semesta, maka pembagian bintang-bintang yang tampak dan tidak tampak tidaklah akan sama. l.[n 4]

Sistem Ptolemaik

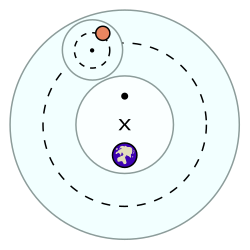

Dalam Sistem Ptolemaik, setiap planet digerakkan oleh suatu sistem yang memuat dua bola atau lebih: satu disebut "deferent" yang lain "epicycle" .

Sekalipun model geosentrik digantikan oleh model heliosentrik. Namun, model deferent dan epicycle tetap dipakai karena menghasilkan prediksi yang akurat dan lebih sesuai dengan pengamatan dibanding sistem-sistem lain. Epicycle Venus dan Mercurius selalu berpusat pada suatu garis antara Bumi dan Matahari (Merkurius lebih dekat ke Bumi), yang menjelaskan mengapa kedua planet itu selalu dekat di langit. Model ini digantikan oleh model eliptik Kepler hanya ketika metode pengamatan (yang dikembangkan oleh Tycho Brahe dan lain-lain) menjadi cukup akurat untuk meragukan model epicycle.

Urutan lingkaran-lingkaran orbit dari bumi ke luar adalah:[8]

- Bulan

- Merkurius

- Venus

- Matahari

- Mars

- Jupiter

- Saturnus

- Bintang-bintang tetap

- Primum Mobile ("Yang pertama bergerak").

Urutan ini tidak diciptakan atau merupakan hasil karya Ptolemaeus, melainkan diselaraskan dengan kosmologi agamawi "Tujuh Langit" yang umum ditemui pada tradisi agamawi Eurasia utama.

Geosentrisme dan Astronomi Islam

Dikarenakan dominansi ilmiah sistem Ptolemaik dalam astronomi Islam, para astronom Muslim menerima bulat model geosentrik.[n 5]

Geosentrisme dan sistem-sistem saingan

Tidak semua orang Yunani setuju dengan model geosentrik. Sistem Pythagorean yang sudah disinggung sebelumnya meyakini bahwa Bumi merupakan salah satu dari beberapa planet yang bergerak mengelilingi suatu api di tengah-tengah.[10] Hicetas dan Ecphantus, dua penganut Pythagorean dari abad ke-5 SM, dan Heraclides Ponticus dari abad ke-4 SM, percaya bahwa Bumi berputra mengelilingi aksisnya, tetapi tetap berada di tengah alam semesta.[11] Sistem semacam itu masih tergolong geosentrik. Pandangan ini dibangkitkan kembali pada Abad Pertengahan oleh Jean Buridan. Heraclides Ponticus suatu ketika dianggap berpandangan bahwa baik Venus maupun Merkurius mengelilingi Matahari, bukan Bumi, tetapi anggapan ini tidak lagi diterima.[12] Martianus Capella secara definitif menempatkan Merkurius dan Venus pada suatu orbit mengitari Matahari.[13] Aristarchus dari Samos adalah yang paling radikal, dengan menulis dalam karyanya (yang tidak lagi terlestarikan) mengenai heliosentrisme, bahwa Matahari adalah pusat alam semesta, sedangkan Bumi dan planet-planet lain mengitarinya.[14] Teorinya tidak populer pada masanya, dan ia mempunyai satu pengikut yang bernama, Seleucus of Seleucia.[15]

Ini menunjukkan bahwa dengan kosmologi Ptolemaik, epicycle Venus tidak dapat sepenuhnya di dalam maupun di luar orbit matahari. Akibatnya, pada sistem Ptolemaik pandangan bahwa epicycle Venus sepenuhnya di dalam matahari ditinggalkan, dan kemudian pada abad ke-17 kompetisi antara kosmologi astronomi berfokus pada variasi sistem Tychonik yang dikemukakan oleh Tycho Brahe, di mana Bumi masih menjadi pusat alam semesta, dikitari oleh matahari, tetapi semua planet lain berputar mengelilingi matahari sebagi suatu himpunan epicycle masif), atau variasi-variasi Sistem Kopernikan.

Penganut geosentrisme agamawi dan kontemporari

Yudaisme Ortodoks

Sejumlah pemimpin Yudaisme Ortodoks, terutama Lubavitcher Rebbe, mempertahankan model geosentrik alam semesta berdasarkan ayat-ayat Alkitab dan penafsiran Maimonides sehingga ia mengajarkan bahwa bumi dikitari oleh matahari.[16][17] Lubavitcher Rebbe juga menjelaskan bahwa geosentrisme dapat dipertahankan berdasarkan teori Relativitas, dimana dinyatakan bahwa "ketika dua benda di udara bergerak relatif satu sama lain, ... ilmu alam mendeklarasikan dengan kepastian absolut bahwa dari segi sudut pandang ilmiah kedua kemungkinan itu valid, yaitu bumi mengitari matahari, atau matahari mengitari bumi."[18]

Meskipun geosentrisme penting untuk perhitungan kalender Maimonides,[19] mayoritas sarjana agamawi Yahudi, yang menerima keilahian Alkitab dan menerima banyak aturan-aturannya mengikat secara hukum, tidak percaya bahwa Alkitab maupun Maimonides memerintahkan untuk percaya pada geosentrisme.[17][20] Namun, ada bukti bahwa kepercayaan geosentrisme meningkat di antara umat Yahudi Ortodoks..[16][17]

Islam

Kasus-kasus prominent geosentrisme modern dalam Islam sangat terisolasi. Hanya sedikit individu yang mengajarkan suatu pandangan geosentrik alam semesta. Salah satunya adalah Grand Mufti Saudi Arabia tahun 1993-1999, Abd al-Aziz ibn Abd Allah ibn Baaz (Ibn Baz), yang mengajarkan pandangan ini antara tahun 1966-1985.

Planetarium

Model geosentrik (Ptolemaik) tata surya terus digunakan oleh para pembuat planetarium karena berdasarkan alasan teknis pergerakan tipe Ptolemaik untuk aparatus cahaya planet memiliki sejumlah kelebihan dibandingkan teori pergerakan Kopernikus.[21] Sistem bulatan selestial yang digunakan untuk tujuan pengajaran dan navigasi juga didasarkan pada sistem geosentrik[22] yang mengabaikan efek paralaks. Namun, efek ini dapat diabaikan pada skala akurasi yang diterapkan pada suatu planetarium.

Lihat pula

Catatan

- ^ Alam semesta Mesir secara isi sama dengan alam semesta Babel, yaitu digambarkan seperti kotak persegi panjang dengan orientasi utara-selatan dan dengn permukaan sedikit cembung, di mana Mesir adalah pusatnya. Pandangan astronomi Ibrani kuno yang serupa dapat dilihat dari tulisan-tulisan kitab suci, misalnya teori penciptaan semesta dan berbagai mazmur yang menyebut "cakrawala", bintang-bintang, matahari dan bumi. Orang Ibrani memandang bumi seakan-akan sebagai permukaan datar yang terdiri dari bagian padat dan cair, dan langit sebagai alam cahaya di mana benda-benda langit bergerak. Bumi ditopang oleh batu-batu penjuru dan tidak dapat digerakkan selain oleh Yahweh (misalnya dalam kaitan dengan gempa bumi). Menurut orang Ibrani, matahari dan bulan berjarak dekat satu sama lain[3]

- ^ Gambaran alam semesta dalam teks-teks Talmud adalah bumi di tengah ciptaan dengan langit sebagai bulatan yang dibentangkan di atasnya. Bumi biasanya digambarkan seperti sebuah piring yang dikelilingi oleh air. Yang menarik spekulasi kosmologi dan metafisika tidak ditanamkan dalam publik maupun dilestarikan dalam tulisan. Namun, dianggap lebih sebagai "rahasia-rahasia Taurat yang tidak seharusnya diturunkan semua orang dan kalangan" (Ketubot 112a). Meskipun studi penciptaan Allah tidak dilarang, spekulasi tentang "apa yang ada di atas, di bawah, yang ada sebelumnya dan yang kemudian" (Mishnah Hagigah: 2) dibatasi hanya untuk elite intelektual.[4]

- ^ Sebagaimana Midrash dan Talmud, Targum tidak berpandangan adanya suatu bulatan bumi, melainkan suatu piringan bumi datar, yang dikitari matahari dalam jalur setengah lingkaran yang ditempuh rata-rata dalam 12 jam.[5]

- ^ Argumen ini ditulis pada iBuku I, Bab 5, Almagest.[7]

- ^ "Semua astronom Islam dari Thabit ibn Qurra pada abad ke-9 sampai Ibn al-Shatir pada abad ke-14, dan semua filsuf alamiah dari al-Kindi sampai Averroes dan seterusnya, diketahui telah nemerima ... gambaran dunia menurut budaya Yunani yang terdiri dari dua bulatan, di mana salah satunya, bulatan selestial ... secara bulat membungkus yang lain."[9]

Referensi

- ^ Lawson, Russell M. (2004). Science in the Ancient World: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. hlm. 29–30. ISBN 1851095349.

- ^ Kuhn 1957, hlm. 5-20.

- ^ Abetti, Giorgio (2012). "Cosmology". Encyclopedia Americana (edisi ke-Online). Grolier.

- ^ Tirosh-Samuelson, Hava (2003). "Topic Overview: Judaism". Dalam van Huyssteen, J. Wentzel Vrede. Encyclopedia of Science and Religion. 2. New York: Macmillan Reference USA. hlm. 477–83.

- ^ Gandz, Solomon (1953). "The distribution of land and sea on the Earth's surface according to Hebrew sources". Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research. 22: 23–53.

- ^ Fraser, Craig G. (2006). The Cosmos: A Historical Perspective. hlm. 14.

- ^ Crowe 1990, hlm. 60–2

- ^ Goldstein, Bernard R. (1967). "The Arabic version of Ptolemy's planetary hypothesis". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 57 (pt. 4): 6. JSTOR 1006040.

- ^ Sabra, A. I. (1998). "Configuring the universe: Aporetic, problem solving, and kinematic modeling as themes of Arabic astronomy". Perspectives on Science. 6 (3): 317–8.

- ^ Johansen, K. F.; Rosenmeier, H. (1998). A History of Ancient Philosophy: From the Beginnings to Augustine. hlm. 43.

- ^ Sarton, George (1953). Ancient Science Through the Golden Age of Greece. hlm. 290.

- ^ Eastwood, B. S. (1992-11-01). "Heraclides and heliocentrism – Texts diagrams and interpretations". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 23: 233.

- ^ Lindberg, David C. (2010). The Beginnings of Western Science: The European Scientific Tradition in Philosophical, Religious, and Institutional Context, Prehistory to A.D. 1450 (edisi ke-2nd). University of Chicago Press. hlm. 197. ISBN 9780226482040.

- ^ Lawson 2004, hlm. 19

- ^ Russell, Bertrand (2013) [1945]. A History of Western Philosophy. Routledge. hlm. 215. ISBN 9781134343676.

- ^ a b Nussbaum, Alexander (2007-12-19). "Orthodox Jews & science: An empirical study of their attitudes toward evolution, the fossil record, and modern geology". Skeptic Magazine. Diakses tanggal 2008-12-18.

- ^ a b c Nussbaum, Alexander (January–April 2002). "Creationism and geocentrism among Orthodox Jewish scientists". Reports of the National Center for Science Education: 38–43.

- ^ Schneersohn, Menachem Mendel; Gotfryd, Arnie (2003). Mind over Matter: The Lubavitcher Rebbe on Science, Technology and Medicine. Shamir. hlm. 76ff.; cf. xvi-xvii, 69, 100–1, 171–2, 408ff. ISBN 9789652930804.

- ^ "Sefer Zemanim: Kiddush HaChodesh: Chapter 11". Mishneh Torah. Translated by Touger, Eliyahu. Chabad-Lubavitch Media Center. Halacha 13–14.

- ^ Rabinowitz, Avi (1987). "EgoCentrism and GeoCentrism; Human Significance and Existential Despair; Bible and Science; Fundamentalism and Skepticalism". Science & Religion. Diakses tanggal 2013-12-01. Published in Branover, Herman; Attia, Ilana Coven, ed. (1994). Science in the Light of Torah: A B'Or Ha'Torah Reader. Jason Aronson. ISBN 9781568210346.

- ^ Hort, William Jillard (1822). A General View of the Sciences and Arts. hlm. 182.

- ^ Kaler, James B. (2002). The Ever-changing Sky: A Guide to the Celestial Sphere. hlm. 25.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Hetherington2006" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Rufus1939" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Hartner1955" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Goldstein1972" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Gale" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Setia2004" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Saliba1994" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Dallal1999" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Guessoun2008" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Ragep2001a" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Ragep2001b" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Huff2003" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "KirmaniSingh2005" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Finocchiaro2008" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Densmore2004" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Babinski1995" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Graebner1902" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Numbers1993" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Sefton2006" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Berman2006" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "Crabtree1999" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

Kesalahan pengutipan: Tag <ref> dengan nama "MillerBio" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.

<ref> dengan nama "Dean2005" yang didefinisikan di <references> tidak digunakan pada teks sebelumnya.Pustaka

- Crowe, Michael J. (1990). Theories of the World from Antiquity to the Copernican Revolution. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 0486261735.

- Dreyer, J.L.E. (1953). A History of Astronomy from Thales to Kepler. New York: Dover Publications.

- Evans, James (1998). The History and Practice of Ancient Astronomy. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Heath, Thomas (1913). Aristarchus of Samos. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Hoyle, Fred (1973). Nicolaus Copernicus.

- Koestler, Arthur (1986) [1959]. The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe. Penguin Books. ISBN 014055212X. 1990 reprint: ISBN 0140192468.

- Kuhn, Thomas S. (1957). The Copernican Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674171039.

- Linton, Christopher M. (2004). From Eudoxus to Einstein—A History of Mathematical Astronomy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521827508.

- Walker, Christopher, ed. (1996). Astronomy Before the Telescope. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 0714117463.