Geosentrisme: Perbedaan antara revisi

JohnThorne (bicara | kontrib) Tidak ada ringkasan suntingan |

JohnThorne (bicara | kontrib) Tidak ada ringkasan suntingan |

||

| Baris 23: | Baris 23: | ||

Adherence to the geocentric model stemmed largely from several important observations. First of all, if the Earth did move, then one ought to be able to observe the shifting of the fixed stars due to stellar [[parallax]]. In short, if the earth was moving, the shapes of the [[constellation]]s should change considerably over the course of a year. If they did not appear to move, the stars are either much further away than the Sun and the planets than previously conceived, making their motion undetectable, or in reality they are not moving at all. Because the stars were actually much further away than Greek astronomers postulated (making movement extremely subtle), stellar parallax was not detected until the 19th century. Therefore, the Greeks chose the simpler of the two explanations. The lack of any observable parallax was considered a fatal flaw in any non-geocentric theory. Another observation used in favor of the geocentric model at the time was the apparent consistency of Venus' luminosity, which implies that it is usually about the same distance from Earth, which in turn is more consistent with geocentrism than heliocentrism. In reality, that is because the loss of light caused by Venus' phases compensates for the increase in apparent size caused by its varying distance from Earth. Objections to heliocentrism utilized the natural tendency of terrestrial bodies to come to rest as near as possible to the center of the earth, and barring the opportunity to fall closer the center, not to move unless forced by an outside object, or transformed to a different element by heat or moisture. |

Adherence to the geocentric model stemmed largely from several important observations. First of all, if the Earth did move, then one ought to be able to observe the shifting of the fixed stars due to stellar [[parallax]]. In short, if the earth was moving, the shapes of the [[constellation]]s should change considerably over the course of a year. If they did not appear to move, the stars are either much further away than the Sun and the planets than previously conceived, making their motion undetectable, or in reality they are not moving at all. Because the stars were actually much further away than Greek astronomers postulated (making movement extremely subtle), stellar parallax was not detected until the 19th century. Therefore, the Greeks chose the simpler of the two explanations. The lack of any observable parallax was considered a fatal flaw in any non-geocentric theory. Another observation used in favor of the geocentric model at the time was the apparent consistency of Venus' luminosity, which implies that it is usually about the same distance from Earth, which in turn is more consistent with geocentrism than heliocentrism. In reality, that is because the loss of light caused by Venus' phases compensates for the increase in apparent size caused by its varying distance from Earth. Objections to heliocentrism utilized the natural tendency of terrestrial bodies to come to rest as near as possible to the center of the earth, and barring the opportunity to fall closer the center, not to move unless forced by an outside object, or transformed to a different element by heat or moisture. |

||

Atmospheric explanations for many phenomena were preferred because the Eudoxan–Aristotelian model based on perfectly concentric spheres was not intended to explain changes in the brightness of the planets due to a change in distance.<ref name= "Hetherington2006"/> Eventually, perfectly concentric spheres were abandoned as it wasn't possible to develop a sufficiently accurate model under that ideal. However, while providing for similar explanations, the later [[deferent and epicycle]] model proved to be flexible enough to accommodate observations for many centuries. |

Atmospheric explanations for many phenomena were preferred because the Eudoxan–Aristotelian model based on perfectly concentric spheres was not intended to explain changes in the brightness of the planets due to a change in distance.<ref name= "Hetherington2006">{{cite book |last= Hetherington |first= Norriss S. |title= Planetary Motions: A Historical Perspective |year= 2006 |page= 28}}</ref> Eventually, perfectly concentric spheres were abandoned as it wasn't possible to develop a sufficiently accurate model under that ideal. However, while providing for similar explanations, the later [[deferent and epicycle]] model proved to be flexible enough to accommodate observations for many centuries. |

||

--> |

--> |

||

== Model Ptolemaik == |

== Model Ptolemaik == |

||

| Baris 61: | Baris 61: | ||

Pada abad ke-12, [[Abū Ishāq Ibrāhīm al-Zarqālī|Arzachel]] meninggalkan ide Yunani kuno "pergerakan melingkar uniform" (''[[uniform circular motion]]'') dengan membuat hipotesis bahwa planet [[Merkurius]] bergerak dalam orbit eliptik,<ref name= "Rufus1939">{{Cite journal |title= The influence of Islamic astronomy in Europe and the far east |last= Rufus |first= W. C. |journal= Popular Astronomy |volume= 47 |issue= 5 |date=May 1939 |pages= 233–8}}</ref><ref name= "Hartner1955">{{cite journal |first= Willy |last= Hartner |title= The Mercury horoscope of Marcantonio Michiel of Venice |journal= Vistas in Astronomy |volume= 1 |year= 1955 |pages= 118–22}}</ref> sedangkan [[Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji|Alpetragius]] mengusulkan model planetari yang meninggalkan [[equant]], mekanisme epicycle dan eksentrik,<ref name= "Goldstein1972"/> meskipun ini menghasilkan suatu sistem yang lebih kurang akurat secara matematik.<ref name= "Gale">{{Cite book |chapter= Ptolemaic Astronomy, Islamic Planetary Theory, and Copernicus's Debt to the Maragha School |title= Science and Its Times |publisher= [[Thomson Gale]] |year= 2006}}</ref> [[Fakhr al-Din al-Razi]] (1149–1209), sehubungan dengan konsepsi fisika dan dunia fisika dalam karyanya ''Matalib'', menolak pandangan Aristotelian dan Avicennian bahwa Bumi berada di pusat alam semesta, melainkan berpendapat bahwa ada "ribuan-ribuan dunia (''alfa alfi 'awalim'') di luar dunia ini sedemikian sehingga setiap dunia ini lebih besar dan masif dari dunia ini serta serupa dengan dunia ini." Untuk mendukung argumen teologinya, ia mengutip dari [[Al Quran]], "All praise belongs to God, Lord of the Worlds," menekankan istilah "Worlds" (''dunia-dunia'').<ref name= "Setia2004"/> |

Pada abad ke-12, [[Abū Ishāq Ibrāhīm al-Zarqālī|Arzachel]] meninggalkan ide Yunani kuno "pergerakan melingkar uniform" (''[[uniform circular motion]]'') dengan membuat hipotesis bahwa planet [[Merkurius]] bergerak dalam orbit eliptik,<ref name= "Rufus1939">{{Cite journal |title= The influence of Islamic astronomy in Europe and the far east |last= Rufus |first= W. C. |journal= Popular Astronomy |volume= 47 |issue= 5 |date=May 1939 |pages= 233–8}}</ref><ref name= "Hartner1955">{{cite journal |first= Willy |last= Hartner |title= The Mercury horoscope of Marcantonio Michiel of Venice |journal= Vistas in Astronomy |volume= 1 |year= 1955 |pages= 118–22}}</ref> sedangkan [[Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji|Alpetragius]] mengusulkan model planetari yang meninggalkan [[equant]], mekanisme epicycle dan eksentrik,<ref name= "Goldstein1972"/> meskipun ini menghasilkan suatu sistem yang lebih kurang akurat secara matematik.<ref name= "Gale">{{Cite book |chapter= Ptolemaic Astronomy, Islamic Planetary Theory, and Copernicus's Debt to the Maragha School |title= Science and Its Times |publisher= [[Thomson Gale]] |year= 2006}}</ref> [[Fakhr al-Din al-Razi]] (1149–1209), sehubungan dengan konsepsi fisika dan dunia fisika dalam karyanya ''Matalib'', menolak pandangan Aristotelian dan Avicennian bahwa Bumi berada di pusat alam semesta, melainkan berpendapat bahwa ada "ribuan-ribuan dunia (''alfa alfi 'awalim'') di luar dunia ini sedemikian sehingga setiap dunia ini lebih besar dan masif dari dunia ini serta serupa dengan dunia ini." Untuk mendukung argumen teologinya, ia mengutip dari [[Al Quran]], "All praise belongs to God, Lord of the Worlds," menekankan istilah "Worlds" (''dunia-dunia'').<ref name= "Setia2004"/> |

||

<!-- |

<!-- |

||

The "Maragha Revolution" refers to the Maragha school's revolution against Ptolemaic astronomy. The "Maragha school" was an astronomical tradition beginning in the [[Maragheh observatory|Maragha observatory]] and continuing with astronomers from the [[Umayyad Mosque|Damascus mosque]] and [[Ulugh Beg Observatory|Samarkand observatory]]. Like their [[Al-Andalus|Andalusian]] predecessors, the Maragha astronomers attempted to solve the [[equant]] problem (the circle around whose circumference a planet or the center of an [[epicycle]] was conceived to move uniformly) and produce alternative configurations to the Ptolemaic model without abandoning geocentrism. They were more successful than their Andalusian predecessors in producing non-Ptolemaic configurations which eliminated the equant and eccentrics, were more accurate than the Ptolemaic model in numerically predicting planetary positions, and were in better agreement with empirical observations.<ref name= "Saliba1994"/> The most important of the Maragha astronomers included [[Mo'ayyeduddin Urdi]] (d. 1266), [[Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī]] (1201–1274), [[Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi]] (1236–1311), [[Ibn al-Shatir]] (1304–1375), [[Ali Qushji]] (c. 1474), [[Al-Birjandi]] (d. 1525), and Shams al-Din al-Khafri (d. 1550).<ref name= "Dallal1999"/> [[Ibn al-Shatir]], the Damascene astronomer (1304–1375 AD) working at the [[Umayyad Mosque]], wrote a major book entitled ''Kitab Nihayat al-Sul fi Tashih al-Usul'' (''A Final Inquiry Concerning the Rectification of Planetary Theory'') on a theory which departs largely from the Ptolemaic system known at that time. In his book, "Ibn al-Shatir, an Arab astronomer of the fourteenth century," E. S. Kennedy wrote "what is of most interest, however, is that Ibn al-Shatir's lunar theory, except for trivial differences in parameters, is identical with that of [[Nicolaus Copernicus|Copernicus]] (1473–1543 AD)." The discovery that the models of Ibn al-Shatir are mathematically identical to those of Copernicus suggests the possible transmission of these models to Europe.<ref name= "Guessoun2008"/> At the Maragha and [[Ulugh Beg Observatory|Samarkand observatories]], the [[Earth's rotation]] was discussed by al-Tusi and [[Ali Qushji]] (b. 1403); the arguments and evidence they used resemble those used by Copernicus to support the Earth's motion.<ref name= "Ragep2001a">{{Cite journal |last= Ragep |first= F. Jamil |year= 2001 |title= Tusi and Copernicus: The Earth's motion in context |journal= Science in Context |volume= 14 |issue= 1-2 |pages= 145–163 |publisher= [[Cambridge University Press]]}}</ref> |

The "Maragha Revolution" refers to the Maragha school's revolution against Ptolemaic astronomy. The "Maragha school" was an astronomical tradition beginning in the [[Maragheh observatory|Maragha observatory]] and continuing with astronomers from the [[Umayyad Mosque|Damascus mosque]] and [[Ulugh Beg Observatory|Samarkand observatory]]. Like their [[Al-Andalus|Andalusian]] predecessors, the Maragha astronomers attempted to solve the [[equant]] problem (the circle around whose circumference a planet or the center of an [[epicycle]] was conceived to move uniformly) and produce alternative configurations to the Ptolemaic model without abandoning geocentrism. They were more successful than their Andalusian predecessors in producing non-Ptolemaic configurations which eliminated the equant and eccentrics, were more accurate than the Ptolemaic model in numerically predicting planetary positions, and were in better agreement with empirical observations.<ref name= "Saliba1994">{{cite book |last= Saliba |first= George |authorlink= George Saliba |year= 1994 |title= A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam |pages= 233–234, 240 |publisher= [[New York University Press]] |isbn= 0814780237}}</ref> The most important of the Maragha astronomers included [[Mo'ayyeduddin Urdi]] (d. 1266), [[Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī]] (1201–1274), [[Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi]] (1236–1311), [[Ibn al-Shatir]] (1304–1375), [[Ali Qushji]] (c. 1474), [[Al-Birjandi]] (d. 1525), and Shams al-Din al-Khafri (d. 1550).<ref name= "Dallal1999">{{cite book |first= Ahmad |last= Dallal |year= 1999 |chapter= Science, Medicine and Technology |title= The Oxford History of Islam |page= 171 |editor-first= John |editor-last= Esposito |editor-link= John Esposito |location= New York |publisher= [[Oxford University Press]]}}</ref> [[Ibn al-Shatir]], the Damascene astronomer (1304–1375 AD) working at the [[Umayyad Mosque]], wrote a major book entitled ''Kitab Nihayat al-Sul fi Tashih al-Usul'' (''A Final Inquiry Concerning the Rectification of Planetary Theory'') on a theory which departs largely from the Ptolemaic system known at that time. In his book, "Ibn al-Shatir, an Arab astronomer of the fourteenth century," E. S. Kennedy wrote "what is of most interest, however, is that Ibn al-Shatir's lunar theory, except for trivial differences in parameters, is identical with that of [[Nicolaus Copernicus|Copernicus]] (1473–1543 AD)." The discovery that the models of Ibn al-Shatir are mathematically identical to those of Copernicus suggests the possible transmission of these models to Europe.<ref name= "Guessoun2008">{{cite journal |last= Guessoum |first= N. |date=June 2008 |title= Copernicus and Ibn Al-Shatir: Does the Copernican revolution have Islamic roots? |journal= The Observatory |volume= 128 |pages= 231–9}}</ref> At the Maragha and [[Ulugh Beg Observatory|Samarkand observatories]], the [[Earth's rotation]] was discussed by al-Tusi and [[Ali Qushji]] (b. 1403); the arguments and evidence they used resemble those used by Copernicus to support the Earth's motion.<ref name= "Ragep2001a">{{Cite journal |last= Ragep |first= F. Jamil |year= 2001 |title= Tusi and Copernicus: The Earth's motion in context |journal= Science in Context |volume= 14 |issue= 1-2 |pages= 145–163 |publisher= [[Cambridge University Press]]}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "Ragep2001b">{{Cite journal |last= Ragep |first= F. Jamil |year= 2001 |title= Freeing astronomy from philosophy: An aspect of Islamic influence on science |journal= Osiris |series= 2nd Series |volume= 16 |issue= Science in Theistic Contexts: Cognitive Dimensions |pages= 49–64, 66–71 |doi=10.1086/649338}}</ref> |

<ref name= "Ragep2001b">{{Cite journal |last= Ragep |first= F. Jamil |year= 2001 |title= Freeing astronomy from philosophy: An aspect of Islamic influence on science |journal= Osiris |series= 2nd Series |volume= 16 |issue= Science in Theistic Contexts: Cognitive Dimensions |pages= 49–64, 66–71 |doi=10.1086/649338}}</ref> |

||

| Baris 157: | Baris 157: | ||

|publisher= [[ABC-CLIO]] |isbn= 1851095349 |ref={{Harvid|Lawson|2004}}}}</ref> |

|publisher= [[ABC-CLIO]] |isbn= 1851095349 |ref={{Harvid|Lawson|2004}}}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "Fraser2006">{{cite book |last= Fraser |first= Craig G. |title= The Cosmos: A Historical Perspective |year= 2006 |page= 14}}</ref> |

<ref name= "Fraser2006">{{cite book |last= Fraser |first= Craig G. |title= The Cosmos: A Historical Perspective |year= 2006 |page= 14}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "Hetherington2006">{{cite book |last= Hetherington |first= Norriss S. |title= Planetary Motions: A Historical Perspective |year= 2006 |page= 28}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Goldstein1967">{{cite journal |title= The Arabic version of Ptolemy's planetary hypothesis |first= Bernard R. |last= Goldstein |page= 6 |journal= Transactions of the American Philosophical Society |year= 1967 |volume= 57 |issue= pt. 4 |jstor= 1006040}}</ref> |

<ref name= "Goldstein1967">{{cite journal |title= The Arabic version of Ptolemy's planetary hypothesis |first= Bernard R. |last= Goldstein |page= 6 |journal= Transactions of the American Philosophical Society |year= 1967 |volume= 57 |issue= pt. 4 |jstor= 1006040}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "Goldstein1972">{{cite journal |first= Bernard R. |last= Goldstein |year= 1972 |title= Theory and observation in medieval astronomy |journal= Isis |volume= 63 |issue= 1 |page= 41}}</ref> |

<ref name= "Goldstein1972">{{cite journal |first= Bernard R. |last= Goldstein |year= 1972 |title= Theory and observation in medieval astronomy |journal= Isis |volume= 63 |issue= 1 |page= 41}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "Setia2004">{{Cite journal |title= Fakhr Al-Din Al-Razi on physics and the nature of the physical world: A preliminary survey |first= Adi |last= Setia |journal= Islam & Science |volume= 2 |year= 2004}}</ref> |

<ref name= "Setia2004">{{Cite journal |title= Fakhr Al-Din Al-Razi on physics and the nature of the physical world: A preliminary survey |first= Adi |last= Setia |journal= Islam & Science |volume= 2 |year= 2004}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "Saliba1994">{{cite book |last= Saliba |first= George |authorlink= George Saliba |year= 1994 |title= A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam |pages= 233–234, 240 |publisher= [[New York University Press]] |isbn= 0814780237}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Dallal1999">{{cite book |first= Ahmad |last= Dallal |year= 1999 |chapter= Science, Medicine and Technology |title= The Oxford History of Islam |page= 171 |editor-first= John |editor-last= Esposito |editor-link= John Esposito |location= New York |publisher= [[Oxford University Press]]}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "Guessoun2008">{{cite journal |last= Guessoum |first= N. |date=June 2008 |title= Copernicus and Ibn Al-Shatir: Does the Copernican revolution have Islamic roots? |journal= The Observatory |volume= 128 |pages= 231–9}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name= "JohansenRosenmeier1998">{{cite book |first1= K. F. |last1=Johansen |first2= H. |last2= Rosenmeier |title= A History of Ancient Philosophy: From the Beginnings to Augustine |year= 1998 |page= 43}}</ref> |

<ref name= "JohansenRosenmeier1998">{{cite book |first1= K. F. |last1=Johansen |first2= H. |last2= Rosenmeier |title= A History of Ancient Philosophy: From the Beginnings to Augustine |year= 1998 |page= 43}}</ref> |

||

<ref name= "Sarton1953">{{cite book |first= George |last= Sarton |title= Ancient Science Through the Golden Age of Greece |year= 1953 |page= 290}}</ref> |

<ref name= "Sarton1953">{{cite book |first= George |last= Sarton |title= Ancient Science Through the Golden Age of Greece |year= 1953 |page= 290}}</ref> |

||

Revisi per 3 Maret 2014 18.16

Geosentrisme atau disebut Teori Geosentrik, Model Geosentrik (bahasa Inggris: geocentric model atau geocentrism, Ptolemaic system) adalah istilah astronomi yang menggambarkan alam semesta dengan bumi sebagai pusatnya dan pusat pergerakan semua benda-benda langit. Model ini menjadi sistem kosmologi predominan pada budaya kuno misalnya Yunani kuno, yang meliputi sistem-sistem terkenal yang dikemukakan oleh Aristoteles and Claudius Ptolemaeus.[1]

Dua pengamatan umum mendukung pandangan bahwa Bumi adalah pusat dari alam semesta. Pengamatan pertama adalah bintang-bintang, matahari dan planet-planet nampak berputar mengitari bumi setiap hari, membuat bumi adalah pusat sistem ini. Lebih lanjut, setiap bintang berada pada suatu bulatan stelar atau selestial ("stellar sphere" atau "celestial sphere"), di mana bumi adalah pusatnya, yang berkeliling setiap hari, di seputar garis yang menghubungkan kutub utara dan selatan sebagai aksisnya. Bintang-bintang yang terdekat dengan khatulistiwa nampak naik dan turun paling jauh, tetapi setiap bintang kembali ke titik terbitnya setiap hari.[2] Observasi umum kedua yang mendukung model geosentrik adalah bumi nampaknya tidak bergerak dari sudut pandang pengamat yang berada di bumi, bahwa bumi itu solid, stabil dan tetap di tempat. Dengan kata lain, benar-benar dalam posisi diam.

Model geosentrik biasanya dikombinasi dengan suatu Bumi yang bulat oleh filsuf Romawi kuno dan abad pertengahan. Ini tidak sama dengan pandangan model Bumi datar yang disiratkan dalam sejumlah mitologi, sebagaimana juga dalah kosmologi kitab-kitab suci dan Latin kuno.[n 1][n 2][n 3]

Yunani kuno

Teori atau model Geosentrik memasuki astronomi dan filsafat Yunani sejak dini; dapat ditelusuri pada peninggalan filsafat sebelum zaman Sokrates. Pada abad ke-6 SM, Anaximander mengemukakan suatu kosmologi dengan bumi berbentuk seperti potongan suatu tiang (sebuah tabung), berada di awang-awang di pusat segala sesuatu. Matahari, Bulan, and planet-planet adalah lubang-lubang dalam roda-roda yang tidak kelihatan yang mengelilingi bumi; melalui lubang-lubang ini manusia dapat melihat api yang tersembunyi. Pada waktu yang sama, para pengikut Pythagoras, yang disebut kelompok Pythagorean, berpendapat bahwa bumi adalah suatu bola (menurut pengamatan gerhana-gerhana), tetapi bukan sebagai pusat, melainkan bergerak mengelilingi suatu api yang tidak nampak. Kemudian pandangan-pandangan ini digabungkan, sehingga kalangan terpelajar Yunani sejak dari abad ke-4 SM berpikir bahwa bumi adalah bola yang menjadi pusat alam semesta.[6]

Model Ptolemaik

Meskipun prinsip dasar geosentrisme Yunani sudah tersusun pada zaman Aristoteles, detail sistem ini belum menjadi standar. Sistem Ptolemaik, yang diutarakan oleh astronomer Helenistik Mesir Claudius Ptolemaeus pada abad ke- 2 M akhirnya berhasil menjadi standar. Karya astronomi utamanya, Almagest, merupakan puncak karya-karya selama berabad-abad-abad oleh para astronom Yunani kuno, Helenistik dan Babilonia; karya itu diterima selama lebih dari satu milenium sebagai model kosmologi yang benar oleh para astronom Eropa dan Islam. Karena begitu kuat pengaruhnya, sistem Ptolemaik kadang kala dianggap sama dengan model geosentrik.

Ptolemy berpendapat bahwa bumi adalah pusat alam semesta berdasarkan pengamatan sederhana yaitu setengah jumlah bintang-bintang terletak di atas horizon dan setengahnya di bawah horizon pada waktu manapun (bintang-bintang pada bulatan orbitnya), dan anggapan bahwa bintang–bintang semuanya terletak pada suatu jarak tertentu dari pusat semesta. Jika bumi terletak cukup jauh dari pusat semesta, maka pembagian bintang-bintang yang tampak dan tidak tampak tidaklah akan sama. l.[n 4]

Sistem Ptolemaik

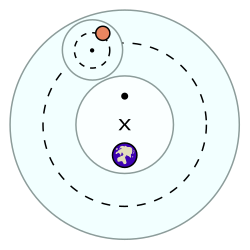

Dalam Sistem Ptolemaik, setiap planet digerakkan oleh suatu sistem yang memuat dua bola atau lebih: satu disebut "deferent" yang lain "epicycle" .

Sekalipun model geosentrik digantikan oleh model heliosentrik. Namun, model deferent dan epicycle tetap dipakai karena menghasilkan prediksi yang akurat dan lebih sesuai dengan pengamatan dibanding sistem-sistem lain. Epicycle Venus dan Mercurius selalu berpusat pada suatu garis antara Bumi dan Matahari (Merkurius lebih dekat ke Bumi), yang menjelaskan mengapa kedua planet itu selalu dekat di langit. Model ini digantikan oleh model eliptik Kepler hanya ketika metode pengamatan (yang dikembangkan oleh Tycho Brahe dan lain-lain) menjadi cukup akurat untuk meragukan model epicycle.

Urutan lingkaran-lingkaran orbit dari bumi ke luar adalah:[8]

- Bulan

- Merkurius

- Venus

- Matahari

- Mars

- Jupiter

- Saturnus

- Bintang-bintang tetap

- Primum Mobile ("Yang pertama bergerak").

Urutan ini tidak diciptakan atau merupakan hasil karya Ptolemaeus, melainkan diselaraskan dengan kosmologi agamawi "Tujuh Langit" yang umum ditemui pada tradisi agamawi Eurasia utama.

Geosentrisme dan Astronomi Islam

Dikarenakan dominansi ilmiah sistem Ptolemaik dalam astronomi Islam, para astronom Muslim menerima bulat model geosentrik.[n 5]

Pada abad ke-12, Arzachel meninggalkan ide Yunani kuno "pergerakan melingkar uniform" (uniform circular motion) dengan membuat hipotesis bahwa planet Merkurius bergerak dalam orbit eliptik,[10][11] sedangkan Alpetragius mengusulkan model planetari yang meninggalkan equant, mekanisme epicycle dan eksentrik,[12] meskipun ini menghasilkan suatu sistem yang lebih kurang akurat secara matematik.[13] Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (1149–1209), sehubungan dengan konsepsi fisika dan dunia fisika dalam karyanya Matalib, menolak pandangan Aristotelian dan Avicennian bahwa Bumi berada di pusat alam semesta, melainkan berpendapat bahwa ada "ribuan-ribuan dunia (alfa alfi 'awalim) di luar dunia ini sedemikian sehingga setiap dunia ini lebih besar dan masif dari dunia ini serta serupa dengan dunia ini." Untuk mendukung argumen teologinya, ia mengutip dari Al Quran, "All praise belongs to God, Lord of the Worlds," menekankan istilah "Worlds" (dunia-dunia).[14]

Geosentrisme dan sistem-sistem saingan

Tidak semua orang Yunani setuju dengan model geosentrik. Sistem Pythagorean yang sudah disinggung sebelumnya meyakini bahwa Bumi merupakan salah satu dari beberapa planet yang bergerak mengelilingi suatu api di tengah-tengah.[15] Hicetas dan Ecphantus, dua penganut Pythagorean dari abad ke-5 SM, dan Heraclides Ponticus dari abad ke-4 SM, percaya bahwa Bumi berputra mengelilingi aksisnya, tetapi tetap berada di tengah alam semesta.[16] Sistem semacam itu masih tergolong geosentrik. Pandangan ini dibangkitkan kembali pada Abad Pertengahan oleh Jean Buridan. Heraclides Ponticus suatu ketika dianggap berpandangan bahwa baik Venus maupun Merkurius mengelilingi Matahari, bukan Bumi, tetapi anggapan ini tidak lagi diterima.[17] Martianus Capella secara definitif menempatkan Merkurius dan Venus pada suatu orbit mengitari Matahari.[18] Aristarchus dari Samos adalah yang paling radikal, dengan menulis dalam karyanya (yang tidak lagi terlestarikan) mengenai heliosentrisme, bahwa Matahari adalah pusat alam semesta, sedangkan Bumi dan planet-planet lain mengitarinya.[19] Teorinya tidak populer pada masanya, dan ia mempunyai satu pengikut yang bernama, Seleucus of Seleucia.[20]

Ini menunjukkan bahwa dengan kosmologi Ptolemaik, epicycle Venus tidak dapat sepenuhnya di dalam maupun di luar orbit matahari. Akibatnya, pada sistem Ptolemaik pandangan bahwa epicycle Venus sepenuhnya di dalam matahari ditinggalkan, dan kemudian pada abad ke-17 kompetisi antara kosmologi astronomi berfokus pada variasi sistem Tychonik yang dikemukakan oleh Tycho Brahe, di mana Bumi masih menjadi pusat alam semesta, dikitari oleh matahari, tetapi semua planet lain berputar mengelilingi matahari sebagi suatu himpunan epicycle masif), atau variasi-variasi Sistem Kopernikan.

Penganut geosentrisme agamawi dan kontemporari

Model Ptolemaik mengenai tata surya masih terus dianut sampai ke awal zaman modern. Sejak akhir abad ke-16 dan seterusnya perlahan-lahan digantikan sebagai penggambaran konsensus oleh model heliosentrisme. Geosentrisme sebagai suatu kepercayaan agamawi terpisah, tidak pernah padam. Di Amerika Serikat antara tahun 1870-1920, misalnya, berbagai anggota Gereja Lutheran – Sinode Missouri menerbitkan artikel-artikel yang menyerang sistem astronomi Kopernikan, dan geosentrisme banyak diajarkan di dalam sinode dalam periode tersebut.[21] Namun, pada tahun 1902 Theological Quarterly, A. L. Graebner menyatakan bahwa sinode itu tidak mempunyai posisi doktrinal terhadap geosentrisme, heliosentrisme, atau model ilmiah lainnya, kecuali kalau itu bertolak belakang dengan Alkitab. Ia menyatakan pula bahwa deklarasi apapun yang dikemukakan para penganut geosentrisme di dalam sinode bukan merupakan pendapat badan gereja secara keseluruhan.[22]

Artikel-artikel yang mendukung geosentrisme sebagai pandangan Alkitab muncul pada sejumlah surat kabar sains penciptaan yang berhubungan dengan Creation Research Society. Umumnya menunjuk kepada beberapa nas Alkitab, yang secara harfiah mengindikasikan pergerakan harian Matahari dan Bulan yang dapat diamati mengelilingi Bumi, bukan karena rotasi Bumi pada aksisnya, misalnya pada Yosua 10:12 di mana Matahari dan Bulan dikatakan berhenti di langit, dan Mazmur 93:1 di mana dunia digambarkan tidak bergerak.[23] Para pendukung kontemporer kepercayaan agamawi itu termasuk Robert Sungenis (presiden dariBellarmine Theological Forum dan pengarang buku terbitan tahun 2006 Galileo Was Wrong (Galileo keliru)).[24] Orang-orang ini mengajarkan pandangan bahwa pembacaan langsung Alkitab memuat kisah akurat bagaimana alam semesta diciptakan dan membutuhkan pandangan geosentrik. Kebanyakan organisasi kreasionis kontemporer menolak pandangan ini.[n 6]

After all, Copernicanism was the first major victory of science over religion, so it's inevitable that some folks would think that everything that's wrong with the world began there. (Steven Dutch of the University of Wisconsin–Madison [26]

Morris Berman mengutip bahwa hasil survei menyatakan saat ini sekitar 20% penduduk Amerika Serikat percaya bahwa matahari mengitari bumi (geosentrisme) bukan bumi mengitari matahari (heliosentrisme), sementara 9% mengatakan tidak tahu.[27] Beberapa poll yang dilakukan oleh Gallup pada tahun 1990-an mendapati bahwa 16% orang Jermans, 18% orang Amerika dan 19% orang Inggris/Britania Raya percaya bahwa Matahari mengitari Bumi.[28] Suatu studi yang dilakukan pada tahun 2005 oleh Jon D. Miller dari Northwestern University, seorang pakar pemahaman publik akan sains dan teknologi,[29] mendapati sekitar 20%, atau seperlima, orang dewasa Amerika percaya bahwa Matahari mengitari Bumi.[30] Menurut poll tahun 2011 oleh VTSIOM, 32% orang Russia percaya bahwa Matahari mengitari Bumi.[31]

Posisi historis hierarki Katolik Roma

Galileo affair yang terkenal menghadapkan model geosentrik dengan pernyataan Galileo. Mengenai basis teologi dari argumen semacam itu, dua orang Paus membahas pertanyaan apakah penggunaan bahasa fenomenologi (berdasarkan pengamatan) akan memaksa orang mengakui kesalahan Alkitab. Keduanya mengajarkan bahwa tidak demikian halnya.

Yudaisme Ortodoks

Sejumlah pemimpin Yudaisme Ortodoks, terutama Lubavitcher Rebbe, mempertahankan model geosentrik alam semesta berdasarkan ayat-ayat Alkitab dan penafsiran Maimonides sehingga ia mengajarkan bahwa bumi dikitari oleh matahari.[32][33] Lubavitcher Rebbe juga menjelaskan bahwa geosentrisme dapat dipertahankan berdasarkan teori Relativitas, dimana dinyatakan bahwa "ketika dua benda di udara bergerak relatif satu sama lain, ... ilmu alam mendeklarasikan dengan kepastian absolut bahwa dari segi sudut pandang ilmiah kedua kemungkinan itu valid, yaitu bumi mengitari matahari, atau matahari mengitari bumi."[34]

Meskipun geosentrisme penting untuk perhitungan kalender Maimonides,[35] mayoritas sarjana agamawi Yahudi, yang menerima keilahian Alkitab dan menerima banyak aturan-aturannya mengikat secara hukum, tidak percaya bahwa Alkitab maupun Maimonides memerintahkan untuk percaya pada geosentrisme.[33][36] Namun, ada bukti bahwa kepercayaan geosentrisme meningkat di antara umat Yahudi Ortodoks.[32][33]

Islam

Kasus-kasus prominent geosentrisme modern dalam Islam sangat terisolasi. Hanya sedikit individu yang mengajarkan suatu pandangan geosentrik alam semesta. Salah satunya adalah Grand Mufti Saudi Arabia tahun 1993-1999, Abd al-Aziz ibn Abd Allah ibn Baaz (Ibn Baz), yang mengajarkan pandangan ini antara tahun 1966-1985.

Planetarium

Model geosentrik (Ptolemaik) tata surya terus digunakan oleh para pembuat planetarium karena berdasarkan alasan teknis pergerakan tipe Ptolemaik untuk aparatus cahaya planet memiliki sejumlah kelebihan dibandingkan teori pergerakan Kopernikus.[37] Sistem bulatan selestial yang digunakan untuk tujuan pengajaran dan navigasi juga didasarkan pada sistem geosentrik[38] yang mengabaikan efek paralaks. Namun, efek ini dapat diabaikan pada skala akurasi yang diterapkan pada suatu planetarium.

Lihat pula

Catatan

- ^ Alam semesta Mesir secara isi sama dengan alam semesta Babel, yaitu digambarkan seperti kotak persegi panjang dengan orientasi utara-selatan dan dengn permukaan sedikit cembung, di mana Mesir adalah pusatnya. Pandangan astronomi Ibrani kuno yang serupa dapat dilihat dari tulisan-tulisan kitab suci, misalnya teori penciptaan semesta dan berbagai mazmur yang menyebut "cakrawala", bintang-bintang, matahari dan bumi. Orang Ibrani memandang bumi seakan-akan sebagai permukaan datar yang terdiri dari bagian padat dan cair, dan langit sebagai alam cahaya di mana benda-benda langit bergerak. Bumi ditopang oleh batu-batu penjuru dan tidak dapat digerakkan selain oleh Yahweh (misalnya dalam kaitan dengan gempa bumi). Menurut orang Ibrani, matahari dan bulan berjarak dekat satu sama lain[3]

- ^ Gambaran alam semesta dalam teks-teks Talmud adalah bumi di tengah ciptaan dengan langit sebagai bulatan yang dibentangkan di atasnya. Bumi biasanya digambarkan seperti sebuah piring yang dikelilingi oleh air. Yang menarik spekulasi kosmologi dan metafisika tidak ditanamkan dalam publik maupun dilestarikan dalam tulisan. Namun, dianggap lebih sebagai "rahasia-rahasia Taurat yang tidak seharusnya diturunkan semua orang dan kalangan" (Ketubot 112a). Meskipun studi penciptaan Allah tidak dilarang, spekulasi tentang "apa yang ada di atas, di bawah, yang ada sebelumnya dan yang kemudian" (Mishnah Hagigah: 2) dibatasi hanya untuk elite intelektual.[4]

- ^ Sebagaimana Midrash dan Talmud, Targum tidak berpandangan adanya suatu bulatan bumi, melainkan suatu piringan bumi datar, yang dikitari matahari dalam jalur setengah lingkaran yang ditempuh rata-rata dalam 12 jam.[5]

- ^ Argumen ini ditulis pada iBuku I, Bab 5, Almagest.[7]

- ^ "Semua astronom Islam dari Thabit ibn Qurra pada abad ke-9 sampai Ibn al-Shatir pada abad ke-14, dan semua filsuf alamiah dari al-Kindi sampai Averroes dan seterusnya, diketahui telah menerima ... gambaran dunia menurut budaya Yunani yang terdiri dari dua bulatan, di mana salah satunya, bulatan selestial ... secara bulat membungkus yang lain."[9]

- ^ Donald B. DeYoung, misalnya, menyatakan bahwa "Similar terminology is often used today when we speak of the sun's rising and setting, even though the earth, not the sun, is doing the moving. Bible writers used the 'language of appearance,' just as people always have. Without it, the intended message would be awkward at best and probably not understood clearly. When the Bible touches on scientific subjects, it is entirely accurate."[25]

Referensi

- ^ Lawson, Russell M. (2004). Science in the Ancient World: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. hlm. 29–30. ISBN 1851095349.

- ^ Kuhn 1957, hlm. 5-20.

- ^ Abetti, Giorgio (2012). "Cosmology". Encyclopedia Americana (edisi ke-Online). Grolier.

- ^ Tirosh-Samuelson, Hava (2003). "Topic Overview: Judaism". Dalam van Huyssteen, J. Wentzel Vrede. Encyclopedia of Science and Religion. 2. New York: Macmillan Reference USA. hlm. 477–83.

- ^ Gandz, Solomon (1953). "The distribution of land and sea on the Earth's surface according to Hebrew sources". Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research. 22: 23–53.

- ^ Fraser, Craig G. (2006). The Cosmos: A Historical Perspective. hlm. 14.

- ^ Crowe 1990, hlm. 60–2

- ^ Goldstein, Bernard R. (1967). "The Arabic version of Ptolemy's planetary hypothesis". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 57 (pt. 4): 6. JSTOR 1006040.

- ^ Sabra, A. I. (1998). "Configuring the universe: Aporetic, problem solving, and kinematic modeling as themes of Arabic astronomy". Perspectives on Science. 6 (3): 317–8.

- ^ Rufus, W. C. (May 1939). "The influence of Islamic astronomy in Europe and the far east". Popular Astronomy. 47 (5): 233–8.

- ^ Hartner, Willy (1955). "The Mercury horoscope of Marcantonio Michiel of Venice". Vistas in Astronomy. 1: 118–22.

- ^ Goldstein, Bernard R. (1972). "Theory and observation in medieval astronomy". Isis. 63 (1): 41.

- ^ "Ptolemaic Astronomy, Islamic Planetary Theory, and Copernicus's Debt to the Maragha School". Science and Its Times. Thomson Gale. 2006.

- ^ Setia, Adi (2004). "Fakhr Al-Din Al-Razi on physics and the nature of the physical world: A preliminary survey". Islam & Science. 2.

- ^ Johansen, K. F.; Rosenmeier, H. (1998). A History of Ancient Philosophy: From the Beginnings to Augustine. hlm. 43.

- ^ Sarton, George (1953). Ancient Science Through the Golden Age of Greece. hlm. 290.

- ^ Eastwood, B. S. (1992-11-01). "Heraclides and heliocentrism – Texts diagrams and interpretations". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 23: 233.

- ^ Lindberg, David C. (2010). The Beginnings of Western Science: The European Scientific Tradition in Philosophical, Religious, and Institutional Context, Prehistory to A.D. 1450 (edisi ke-2nd). University of Chicago Press. hlm. 197. ISBN 9780226482040.

- ^ Lawson 2004, hlm. 19

- ^ Russell, Bertrand (2013) [1945]. A History of Western Philosophy. Routledge. hlm. 215. ISBN 9781134343676.

- ^ Babinski, E. T., ed. (1995). "Excerpts from Frank Zindler's 'Report from the center of the universe' and 'Turtles all the way down'". Cretinism of Evilution. TalkOrigins Archive (2). Diakses tanggal 2013-12-01.

- ^ Graebner, A. L. (1902). "Science and the church". Theological Quarterly. St. Louis, MO: Lutheran Synod of Missouri, Ohio and other states, Concordia Publishing. 6: 37–45.

- ^ Numbers, Ronald L. (1993). The Creationists: The Evolution of Scientific Creationism. University of California Press. hlm. 237. ISBN 0520083938.

- ^ Sefton, Dru (2006-03-30). "In this world view, the sun revolves around the earth". Times-News. Hendersonville, NC. hlm. 5A.

- ^ DeYoung, Donald B. (1997-11-05). "Astronomy and the Bible: Selected questions and answers excerpted from the book". Answers in Genesis. Diakses tanggal 2013-12-01.

- ^ Geocentrism lives

- ^ Berman, Morris (2006). Dark Ages America: The Final Phase of Empire. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393058666.

- ^ Crabtree, Steve (1999-07-06). "New Poll Gauges Americans' General Knowledge Levels". Gallup.

- ^ "Jon D. Miller". Northwestern University website. Diakses tanggal 2007-07-19.

- ^ Dean, Cornelia (2005-08-30). "Scientific savvy? In U.S., not much". New York Times. Diakses tanggal 2007-07-19.

- ^ 'СОЛНЦЕ - СПУТНИК ЗЕМЛИ', ИЛИ РЕЙТИНГ НАУЧНЫХ ЗАБЛУЖДЕНИЙ РОССИЯН (dalam bahasa Rusia) (Пресс-выпуск №1684 [Press release no. 1684]), ВЦИОМ [All-Russian Center for the Study of Public Opinion], 2011-02-08.

- ^ a b Nussbaum, Alexander (2007-12-19). "Orthodox Jews & science: An empirical study of their attitudes toward evolution, the fossil record, and modern geology". Skeptic Magazine. Diakses tanggal 2008-12-18.

- ^ a b c Nussbaum, Alexander (January–April 2002). "Creationism and geocentrism among Orthodox Jewish scientists". Reports of the National Center for Science Education: 38–43.

- ^ Schneersohn, Menachem Mendel; Gotfryd, Arnie (2003). Mind over Matter: The Lubavitcher Rebbe on Science, Technology and Medicine. Shamir. hlm. 76ff.; cf. xvi-xvii, 69, 100–1, 171–2, 408ff. ISBN 9789652930804.

- ^ "Sefer Zemanim: Kiddush HaChodesh: Chapter 11". Mishneh Torah. Translated by Touger, Eliyahu. Chabad-Lubavitch Media Center. Halacha 13–14.

- ^ Rabinowitz, Avi (1987). "EgoCentrism and GeoCentrism; Human Significance and Existential Despair; Bible and Science; Fundamentalism and Skepticalism". Science & Religion. Diakses tanggal 2013-12-01. Published in Branover, Herman; Attia, Ilana Coven, ed. (1994). Science in the Light of Torah: A B'Or Ha'Torah Reader. Jason Aronson. ISBN 9781568210346.

- ^ Hort, William Jillard (1822). A General View of the Sciences and Arts. hlm. 182.

- ^ Kaler, James B. (2002). The Ever-changing Sky: A Guide to the Celestial Sphere. hlm. 25.

Pustaka

- Crowe, Michael J. (1990). Theories of the World from Antiquity to the Copernican Revolution. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 0486261735.

- Dreyer, J.L.E. (1953). A History of Astronomy from Thales to Kepler. New York: Dover Publications.

- Evans, James (1998). The History and Practice of Ancient Astronomy. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Heath, Thomas (1913). Aristarchus of Samos. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Hoyle, Fred (1973). Nicolaus Copernicus.

- Koestler, Arthur (1986) [1959]. The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe. Penguin Books. ISBN 014055212X. 1990 reprint: ISBN 0140192468.

- Kuhn, Thomas S. (1957). The Copernican Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674171039.

- Linton, Christopher M. (2004). From Eudoxus to Einstein—A History of Mathematical Astronomy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521827508.

- Walker, Christopher, ed. (1996). Astronomy Before the Telescope. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 0714117463.