Varietas bahasa Tionghoa: Perbedaan antara revisi

k Bot: Penggantian teks otomatis (-{{tiongkok-stub}} +{{cina-stub}}) |

k Illchy memindahkan halaman Bahasa Tionghoa lisan ke Varietas bahasa Tionghoa dengan menimpa pengalihan lama: Bukan sebuah bahasa tunggal Tag: Suntingan perangkat seluler Suntingan peramban seluler Suntingan seluler lanjutan |

||

| (25 revisi perantara oleh 21 pengguna tidak ditampilkan) | |||

| Baris 1: | Baris 1: | ||

{{Infobox Language family |

|||

| ⚫ | Kebanyakan pakar bahasa menganggap semua varian bahasa Tionghoa sebagai bagian dari [[rumpun bahasa]] |

||

|name=Bahasa Tionghoa |

|||

|familycolor=Sino-Tibetan |

|||

|fam1=Sino-Tibet |

|||

|child1=[[Bahasa Min]] |

|||

|child2=turunan dari [[Bahasa Tionghoa pertengahan]]{{br}}(lihat peta) |

|||

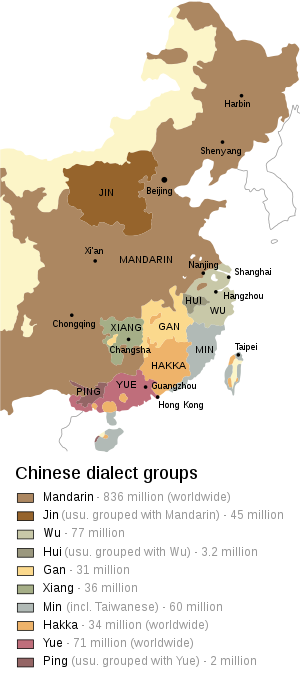

|map=[[Berkas:Map of sinitic languages-en.svg|300px]] |

|||

|map_caption=Cabang utama bahasa Tionghoa |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Bahasa Tionghoa lisan''' ({{zh-st|s=汉语|t=漢語|first=t}}) terdiri atas berbagai macam [[varietas bahasa|varietas]], yang utama adalah [[bahasa Mandarin]], {{bhs|Wu}}, {{bhs|Kanton}}, dan {{bhs|Min}}. Bahasa-bahasa ini untuk alasan-alasan sosiologis dan politis biasanya dikelompokkan menjadi satu kelompok bahasa Tionghoa. |

|||

Istilah ''[[dialek]]'' yang digunakan sebagai padanan kata ''fangyan'' kiranya tidak cukup untuk menggambarkan keperbedaan antara ''fangyan''-''fangyan'' ({{zh-cl|c=方言|l=bahasa daerah}})yang ada. Sama seperti dialek-dialek di Indonesia yang kadang-kadang penggunanya tidak saling memahami satu dengan yang lain, bahkan lebih lagi, demikianlah "varietas" bahasa Tionghoa lisan tidak dapat dipahami antara seorang penutur dengan penutur varietas/dialek yang berbeda. |

|||

{{terjemah}} |

|||

The maps above depict the subdivisions ("languages" or "dialect groups") within Chinese. The seven main groups are [[Mandarin (linguistics)|Mandarin]] (represented by the lines drawn from Beijing), [[Wu (linguistics)|Wu]], [[Xiang (linguistics)|Xiang]], [[Gan (linguistics)|Gan]], [[Hakka (linguistics)|Hakka]], [[Cantonese (linguistics)|Cantonese]], and [[Min (linguistics)|Min]] (which linguists further divide into of 5 to 7 subdivisions on its own, which are all mutually unintelligible). Linguists who distinguish ten instead of seven major groups would then separate [[Jin (linguistics)|Jin]] from Mandarin, [[Ping]] from Yue, and [[Hui (linguistics)|Hui]] from Wu. There are also many smaller groups that confound efforts at classification, such as: [[Dungan language|Dungan]], a dialect of northwestern Mandarin spoken among Chinese-descended Muslims in Kyrghyzstan; [[Danzhou-hua]], spoken on Hainan Island; Xiang-hua 乡话 (not to be confused with Xiang 湘), spoken in western Hunan; and Shaozhou-Tuhua, spoken in northern Guangdong. (An informative article written in Chinese may be found at [http://www.secretchina.com/news/articles/3/6/19/44968b.html].) |

|||

| ⚫ | Kebanyakan pakar bahasa menganggap semua varian bahasa Tionghoa sebagai bagian dari [[rumpun bahasa]] [[Sino-Tibet]] dan mereka percaya bahwa dahulu kala pernah ada sebuah bahasa proto yang mirip situasinya dengan [[Indo-Eropa|bahasa proto Indo-Eropa]] di mana semua bahasa-bahasa Tionghoa, Tibet dan Myanmar adalah bahasa turunannya. Relasi antara bahasa Tionghoa, di satu sisi dengan bahasa Sino-Tibet lainnya masih belum begitu jelas berbeda dengan bahasa-bahasa Indo-Eropa. Para pakar masih secara aktif merekonstruksi bahasa proto Sino-Tibet. Kesulitan utamanya ialah bahwa meskipun banyak sekali dokumentasi di mana kita bisa merekonstruksi bunyi-bunyi bahasa Tionghoa kuno, tidak ada dokumentasi mengenai sejarah perkembangan dari bahasa proto Sino-Tibet menjadi bahasa-bahasa Tionghoa. Selain itu banyak bahasa yang bisa membantu kita merekonstruksi bahasa proto Sino-Tibet, kurang didokumentasikan dan masih belum dikenal dengan baik. |

||

In addition to the previously noted divisions, there is also [[Putonghua]] and [[Guoyu]], the official languages of the [[People's Republic of China]] and the [[Republic of China]], respectively. These are based on the dialect of [[Mandarin (linguistics)|Mandarin]] as spoken in [[Beijing]], and are intended to transcend all of China as a common language of communication. It is therefore the common Chinese language (as these are often called) that is the language of government, of the media, and of instruction in schools. |

|||

There is a lot of controversy around the terminology used to describe the subdivisions of Chinese, with some preferring to call Chinese a [[language]] and its subdivisions [[dialect]]s, and others preferring to call Chinese a [[language family]] and its subdivisions [[language]]s. There is more on this debate later on. On the other hand, even though [[Dungan language|Dungan]] is very closely related to Mandarin, not many people consider it "Chinese", because it is written in Cyrillic and spoken by [[Dungan|people]] outside of [[China]] who are not considered [[Overseas Chinese|Chinese]] in any sense. |

|||

It is common for speakers of Chinese to be able to speak several variations of the language. Typically in southern China, a person will be able to speak the official [[Putonghua]], the local dialect, and occasionally either speak or understand another regional dialect, such as [[Cantonese (linguistics)|Cantonese]]. Such polyglots will frequently [[code-switching|code switch]] between Putonghua and the local dialect, depending on situation. See [[Kapang Syndrome]]. Sometimes, the various dialects are mixed from other dialects, depending on geographical influence. A person living in [[Taiwan]], for example, will commonly mix pronunciations, phrases, and words from [[Mandarin (linguistics)|Mandarin]] and [[Min-nan|Minnan]], and this mixture is considered socially appropriate under many circumstances. |

|||

=== Apakah Bahasa Tionghoa Sebuah Bahasa atau Sebuah Kelompok Bahasa? === |

|||

Spoken Chinese comprises many regional and mutually unintelligible variants. In the West, many people are familiar with the fact that the [[Romance languages]] all derive from [[Latin language|Latin]] and so have many underlying features in common while being mutually unintelligible. The linguistic evolution of Chinese is similar, while the socio-political context is quite different. |

|||

In Europe, political fragmentation created independent states which are roughly the size of Chinese provinces. This created a political desire to create separate cultural and literary standards between nation-states and to standardize the language within a nation-state. In China, |

|||

a single cultural and literary standard continued to exist while at the same time little can be done to standardize the spoken language between different cities and counties. This has been tried since the era of [[Emperor Qin]]. The main reason is because of the wide area span of the country, and communication blockage by mountains and geography. It is common in China that a family moved into mountains to escape from war, and was later discovered by the local government that they are speaking the tone of some hundred years ago. This has created a linguistic context that is very different from that of Europe, and this has profound implications for how to describe spoken variations of Chinese. |

|||

For example, in Europe, the language of a nation-state was usually standardized to be similar to that of the capital, making it easy, for example, to classify a language as French or Spanish. This had the effect of sharpening linguistic differences. A farmer on one side of the border would start to model his speech after Paris while a farmer on the other side would model his speech after Madrid. In China, this standardization did not happen, and so even categorizing variations can be difficult, in part because different dialects merge into each other. As a result, linguists will disagree among themselves as to classification. |

|||

As a result of the above, Chinese people generally consider Chinese to be one single language. In order to describe dialects, Chinese people typically use ''the speech of location'', for example ''Beijing hua'' (北京話/北京话) for the speech of Beijing or ''Shanghai hua'' (上海話/上海话) for the speech of Shanghai — without any "laypeople awareness" that these various ''hua'' are then categorized into "languages" based on mutual intelligibility. So although it is true that many parts of north China are quite homogeneous in language, while in parts of south China, major cities can have dialects that are only marginally intelligible even to close neighbours, these are all regarded as ''hua'' — equal subvariations under a single Chinese language. |

|||

Due to this "self-perception" of a single Chinese language by the majority of its speakers, there are many linguists who follow this definition, and regard Chinese as a single language and its variations as dialects; others follow the intelligibility requirement and consider Chinese to be a group of anywhere from seven to seventeen related "languages", since these languages are not at all mutually intelligible, and show variation comparable to the Romance languages. |

|||

It is to be noted that this distinction can have some political overtones. Describing Chinese as different languages can imply that China should actually be several different nations, and that the Hàn (Chinese) race is in fact several different races. For this reason, some Chinese are uncomfortable with the idea that Chinese is not a single language, as this perception might legitimize secessionist movements. On the other hand, supporters of [[Taiwanese independence]] also tend to be strong promoters of Min- and Hakka-language education. |

|||

However, the linkages between ethnicity, politics, and language can be complex. For example, many Wu, Min, Hakka, and Cantonese speakers, who consider their own tongues to be separate spoken languages, and the Chinese race to be a single entity, do not consider these two positions to be contradictory. Moreover, the government of the [[People's Republic of China]] officially states that China is a multinational nation, and that the term Chinese incorporates groups that do not natively speak Chinese at all. (Those that do speak Chinese are called [[Han Chinese]] — an ethnic and cultural concept, not a political one.) Similarly on Taiwan, one can find supporters of [[Chinese unification]] who are also interested in promoting local language, and supporters of Taiwan independence who have little interest in the topic. |

|||

== Lihat pula == |

== Lihat pula == |

||

| Baris 32: | Baris 19: | ||

* [[Aksara Tionghoa]] |

* [[Aksara Tionghoa]] |

||

* [[Bahasa Mandarin]] |

* [[Bahasa Mandarin]] |

||

* [[Bahasa Tionghoa vernakular]] |

|||

{{ |

{{Bahasa Tionghoa}} |

||

[[Kategori:Varietas bahasa Tionghoa| ]] |

|||

[[Kategori:Bahasa Tionghoa|Tionghoa lisan]] |

[[Kategori:Bahasa Tionghoa|Tionghoa lisan]] |

||

[[de:Baihua]] |

|||

{{bahasa-stub}} |

|||

[[en:Vernacular Chinese]] |

|||

[[fr:Baihua]] |

|||

[[ja:白話]] |

|||

[[ko:백화문]] |

|||

[[nl:Baihua]] |

|||

[[pl:Baihua]] |

|||

[[zh:白话文]] |

|||

[[zh-yue:白話文]] |

|||

Revisi terkini sejak 19 Januari 2024 22.09

Rumpun bahasa Bahasa Tionghoa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persebaran | Tidak diketahui | ||||

| |||||

| Lokasi penuturan | |||||

| |||||

Bahasa Tionghoa lisan (Hanzi tradisional: 漢語; Hanzi sederhana: 汉语) terdiri atas berbagai macam varietas, yang utama adalah bahasa Mandarin, Wu, Kanton, dan Min. Bahasa-bahasa ini untuk alasan-alasan sosiologis dan politis biasanya dikelompokkan menjadi satu kelompok bahasa Tionghoa.

Istilah dialek yang digunakan sebagai padanan kata fangyan kiranya tidak cukup untuk menggambarkan keperbedaan antara fangyan-fangyan (Hanzi: 方言; harfiah: 'bahasa daerah')yang ada. Sama seperti dialek-dialek di Indonesia yang kadang-kadang penggunanya tidak saling memahami satu dengan yang lain, bahkan lebih lagi, demikianlah "varietas" bahasa Tionghoa lisan tidak dapat dipahami antara seorang penutur dengan penutur varietas/dialek yang berbeda.

Kebanyakan pakar bahasa menganggap semua varian bahasa Tionghoa sebagai bagian dari rumpun bahasa Sino-Tibet dan mereka percaya bahwa dahulu kala pernah ada sebuah bahasa proto yang mirip situasinya dengan bahasa proto Indo-Eropa di mana semua bahasa-bahasa Tionghoa, Tibet dan Myanmar adalah bahasa turunannya. Relasi antara bahasa Tionghoa, di satu sisi dengan bahasa Sino-Tibet lainnya masih belum begitu jelas berbeda dengan bahasa-bahasa Indo-Eropa. Para pakar masih secara aktif merekonstruksi bahasa proto Sino-Tibet. Kesulitan utamanya ialah bahwa meskipun banyak sekali dokumentasi di mana kita bisa merekonstruksi bunyi-bunyi bahasa Tionghoa kuno, tidak ada dokumentasi mengenai sejarah perkembangan dari bahasa proto Sino-Tibet menjadi bahasa-bahasa Tionghoa. Selain itu banyak bahasa yang bisa membantu kita merekonstruksi bahasa proto Sino-Tibet, kurang didokumentasikan dan masih belum dikenal dengan baik.

Lihat pula[sunting | sunting sumber]