Sejarah Belanda: Perbedaan antara revisi

Tidak ada ringkasan suntingan |

|||

| (402 revisi perantara oleh 24 pengguna tidak ditampilkan) | |||

| Baris 1: | Baris 1: | ||

{{Sejarah Belanda}} |

|||

'''Sejarah Negeri Belanda''' adalah sejarah bangsa maritim yang tumbuh dan berkembang di daerah tanah rendah [[delta sungai]] yang bermuara ke [[Laut Utara]] di kawasan barat laut benua Eropa. Catatan sejarah Negeri Belanda bermula dengan kurun waktu empat abad manakala daerah ini menjadi perbatasan wilayah [[Kekaisaran Romawi]] yang dijaga militer. Daerah perbatasan ini kian lama kian terdesak serbuan [[suku Jermanik|suku-suku rumpun Jermanik]] yang berpindah ke arah barat. Seiring runtuhnya Kekaisaran Romawi dan bermulanya [[Abad Pertengahan]], tiga suku terbesar dari rumpun bangsa Jermanik tampil menguasai daerah ini, yakni [[bangsa Frisia|orang Frisia]] di sebelah utara serta kawasan pesisir, [[Bahasa Saxon Hilir Belanda|orang Saksen Hilir]] di sebelah timur laut, dan [[orang Franka]] di sebelah selatan. |

|||

Pada Abad Pertengahan, [[wangsa Karoling]] berhasil menguasai daerah ini, dan memperluas wilayah kekuasaan mereka hingga mencakup hampir seluruh kawasan barat Eropa. [[Belanda|Negeri Belanda]] kala itu merupakan bagian dari [[Lorraine Hilir|Kadipaten Lotharingia Hilir]] di dalam wilayah [[Kekaisaran Romawi Suci]] yang didirikan dan diperintah orang Franka. Selama beberapa abad, Negeri Belanda terbagi-bagi menjadi sejumlah swapraja feodal, antara lain [[Kadipaten Brabant|Brabant]], [[Graafschap Holland|Holland]], [[Zeeland]], [[Friesland]], dan [[Kadipaten Geldern|Gelre]], dengan garis perbatasan yang terus-menerus berubah. Belum ada wilayah kesatuan yang setara dengan wilayah negara Belanda sekarang ini. |

|||

'''Sejarah Belanda''' adalah sejarah bangsa bahari yang tumbuh dan berkembang di daerah dataran rendah [[delta sungai]] yang bermuara ke [[Laut Utara]] di kawasan barat laut Eropa. Catatan sejarah Belanda bermula dengan kurun waktu empat abad manakala daerah ini menjadi tapal batas wilayah [[Belanda pada zaman Kekaisaran Romawi|Kekaisaran Romawi]] yang dijaga bala tentara. Daerah tapal batas ini kian lama kian terdesak oleh serbuan [[suku bangsa Jermanik|suku-suku bangsa Jermanik]] yang berpindah ke arah barat. Seiring runtuhnya Kekaisaran Romawi dan bermulanya [[Abad Pertengahan]], tiga [[suku bangsa Jermanik]] terbesar bangkit menguasai daerah ini, yakni [[Frisii|suku bangsa Frisi]] di sebelah utara dan kawasan pesisir, [[Bahasa Saxon Hilir Belanda|suku bangsa Saksen Hilir]] di sebelah timur laut, dan [[suku Franka|suku bangsa Franka]] di sebelah selatan. |

|||

Pada Abad Pertengahan, kaum keturunan [[wangsa Karoling]] berjaya menguasai daerah ini, dan memperluas ruang lingkup kekuasaan mereka ke hampir seluruh kawasan barat Eropa. Negeri [[Belanda]] kala itu merupakan bagian dari [[Lorraine Hilir|Kadipaten Lotharingia Hilir]] di dalam wilayah [[Kekaisaran Romawi Suci]] yang didirikan dan diperintah oleh suku bangsa Franka. Selama beberapa abad, wilayah Belanda terbagi-bagi menjadi sejumlah swapraja feodal seperti [[Kadipaten Brabant|Brabant]], [[Kabupaten Holland|Holland]], [[Zeeland]], [[Friesland]], [[Kadipaten Geldern|Gelre]], dan berbagai swapraja feodal lainnya dengan tapal batas yang berubah-ubah. Belum ada wilayah kesatuan yang sama dengan wilayah negara Belanda sekarang ini. |

|||

Pada 1433, [[Philippe yang Baik|Adipati Burgundia]] berhasil menguasai seluruh |

Pada 1433, [[Philippe yang Baik|Adipati Burgundia]] berhasil menguasai seluruh daerah tanah rendah di Kadipaten Lotharingia Hilir, dan mendirikan swapraja [[Negeri Belanda Burgundia]]. Wilayah swapraja ini meliputi kawasan yang sekarang menjadi wilayah Negeri Belanda, Belgia, Luksemburg, dan sebagian Prancis. |

||

Raja-raja Spanyol yang beragama Katolik menindak keras penyebaran |

Raja-raja Spanyol yang beragama Katolik menindak keras penyebaran agama Kristen Protestan, yang menimbulkan perseteruan antarkelompok masyarakat di dua kawasan yang kini menjadi wilayah negara Belgia dan daerah [[Holandia|Holland]] di Negeri Belanda. [[Pemberontakan Belanda|Pemberontakan rakyat Belanda]] yang berkobar sesudahnya mengakibatkan swapraja Negeri Belanda Burgundia pecah menjadi [[Belanda Spanyol|Negeri Belanda Spanyol]] dan [[Republik Belanda|Perserikatan Provinsi-Provinsi]]. Negeri Belanda Spanyol adalah wilayah di sebelah selatan yang warganya memeluk agama Kristen Katolik dan menuturkan bahasa Prancis maupun bahasa Belanda (kurang lebih meliputi wilayah negara Belgia dan negara Luksemburg sekarang ini), sementara Perserikatan Provinsi-Provinsi adalah wilayah di sebelah utara yang mayoritas warganya beragama Kristen Protestan dan hanya sedikit yang beragama Kristen Katolik penutur bahasa Belanda. Wilayah Perserikatan Provinsi-Provinsi inilah yang menjadi cikal bakal Negeri Belanda modern. |

||

Pada [[masa Keemasan Belanda|Zaman Keemasan Belanda]] yang mencapai puncaknya sekitar tahun 1667, terjadi perkembangan di bidang |

Pada [[masa Keemasan Belanda|Zaman Keemasan Negeri Belanda]] yang mencapai puncaknya sekitar tahun 1667, terjadi perkembangan di bidang usaha dagang, industri, seni rupa, dan [[Daftar tokoh dari Zaman Keemasan Belanda#Ilmu pengetahuan dan filsafat|ilmu pengetahuan]]. Negari Belanda berkembang menjadi sebuah [[imperium Belanda|imperium]] makmur yang menguasai koloni-koloni di berbagai pelosok dunia, dan [[Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie|Kongsi Hindia Timur]] atau Kompeni Belanda muncul sebagai salah satu perusahaan dagang nasional tertua dan terpenting yang berasaskan kewirausahaan dan usaha dagang. |

||

Pada abad ke-18, |

Pada abad ke-18, kedigdayaan dan kemakmuran Negeri Belanda merosot. Negara ini melemah akibat berulang kali berperang melawan negara-negara tetangga yang lebih kuat, yakni [[Peperangan Inggris-Belanda|Inggris]] dan [[Perang Prancis-Belanda|Prancis]]. Kerajaan Inggris merebut [[Nieuw Amsterdam]], koloni Belanda di Amerika Utara, dan mengganti namanya menjadi [[New York]]. Kerusuhan dan [[Periode Tanpa Mangkubumi Kedua#Krisis dan revolusi kaum pendukung Willem van Oranje pada 1747|perseteruan sengit]] timbul di antara [[Orangisme (Republik Belanda)|kaum pendukung Willem van Oranje]] dan [[Patriottentijd|kaum Patriot]]. Revolusi Prancis merembet sampai ke Negeri Belanda selepas tahun 1789, dan bermuara pada pembentukan negara [[Republik Batavia]] pada tahun 1795. Napoleon menjadikan Republik Batavia sebagai salah satu negara satelit Prancis dengan nama [[Kerajaan Hollandia|Kerajaan Holland]] pada tahun 1806, namun kemudian hari hanya menjadi salah satu provinsi Kekaisaran Prancis. |

||

Setelah Napoleon tumbang pada 1813–1815, [[Kerajaan Bersatu Belanda|Kerajaan |

Setelah rezim Napoleon tumbang pada kurun waktu 1813–1815, berdiri [[Kerajaan Bersatu Belanda|Kerajaan Belanda Serikat]] dengan wilayah yang diperluas, dan diperintah [[Wangsa Oranye-Nassau|wangsa Oranje]] selaku kepala monarki yang juga berdaulat atas Belgia dan Luksemburg. Raja Belanda menerapkan pembaharuan-pembaharuan ala Kristen Protestan secara paksa di Belgia, sehingga rakyat Belgia [[Revolusi Belgia|bangkit memberontak pada tahun 1830]], dan akhirnya merdeka pada tahun 1839. Setelah beberapa waktu tunduk pada pemerintah yang berhaluan konservatif, Negeri Belanda menjadi negara [[demokrasi perwakilan|demokrasi parlementer]] yang dikepalai seorang [[kerajaan konstitusional|kepala monarki konstitusional]] berdasarkan konstitusi tahun 1848. Negara Luksemburg modern secara resmi merdeka dari Negeri Belanda pada tahun 1839, namun masih mengakui Raja Belanda sebagai kepala negara sampai dengan tahun 1890. Mulai dari 1890, jabatan kepala negara Luksemburg beralih ke cabang lain dari wangsa Nassau. |

||

Belanda bersikap netral pada [[Perang Dunia I]], |

Negeri Belanda bersikap netral pada [[Perang Dunia I]], tetapi tetap saja diserbu dan diduduki Jerman Nazi pada [[Perang Dunia II]]. Jerman Nazi beserta antek-anteknya menciduk dan membunuh hampir semua warga Yahudi Belanda (yang paling terkenal adalah [[Anne Frank]]). Manakala perlawanan rakyat Belanda semakin sengit, Jerman Nazi menghambat pasokan pangan ke daerah-daerah, sehingga menimbulkan bencana kelaparan dahsyat pada kurun waktu 1944–1945. Pada tahun 1942, Hindia Belanda direbut Jepang, tetapi orang-orang Belanda sudah lebih dahulu menghancurkan sumur-sumur minyak yang sangat dibutuhkan Jepang. [[Indonesia]] memproklamasikan kemerdekaannya pada tahun 1945. [[Suriname]] mendapatkan kemerdekaannya pada tahun 1975. Pada tahun-tahun pascaperang, Negeri Belanda mengalami pemulihan ekonomi (berkat penerapan [[Rencana Marshall]] yang dicetuskan Amerika Serikat), dan selanjutnya menerapkan konsep [[negara kesejahteraan|negara berkesejahteraan]] pada kurun waktu yang aman dan makmur. Negeri Belanda membentuk persekutuan baru di bidang ekonomi dengan Belgia dan Luksemburg, yang dinamakan [[Benelux|Uni Beneluks]]. Ketiga negara ini kelak menjadi anggota pendiri [[Uni Eropa]] dan [[NATO]]. Pada beberapa dasawarsa terakhir ini, ekonomi Negeri Belanda telah terjalin rapat dengan ekonomi negara Jerman, dan kini sangat makmur. |

||

{{Sejarah Negeri-Negeri Dataran Rendah}} |

|||

== Prasejarah (sebelum 800 SM) == |

== Prasejarah (sebelum 800 SM) == |

||

=== Perubahan-perubahan bersejarah atas bentang alam === |

=== Perubahan-perubahan bersejarah atas bentang alam === |

||

Prasejarah kawasan yang kini menjadi Negeri Belanda lebih banyak dipengaruhi letak geografinya yang rendah dan terus-menerus berubah. |

|||

The prehistory of the area that is now the Netherlands was largely shaped by its constantly shifting, low-lying geography. |

|||

{|cellspacing="0" border="0" style="background: white" |

{|cellspacing="0" border="0" style="background: white" |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|[[ |

|[[Berkas:5500vc ex leg.jpg|jmpl|lurus|kiri|Negeri Belanda pada 5500 SM]] |

||

|[[ |

|[[Berkas:3850vc ex leg copy.jpg|jmpl|lurus|kiri|Negeri Belanda pada 3850 SM]] |

||

|[[ |

|[[Berkas:2750vc ex leg copy.jpg|jmpl|lurus|kiri|Negeri Belanda pada 2750 SM]] |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|[[ |

|[[Berkas:500vc ex leg copy.jpg|jmpl|lurus|kiri|Negeri Belanda pada 500 SM]] |

||

|[[ |

|[[Berkas:50nc ex leg copy.jpg|jmpl|lurus|kiri|Negeri Belanda pada 50 M]] |

||

|{{legend|#fff15d| |

|{{legend|#fff15d|Gisik dan gumuk}} |

||

{{legend|#d2d500| |

{{legend|#d2d500|Dataran endapan pasir akibat pasang surut, [[dataran endapan lumpur]] akibat pasang surut, [[rawa asin]]}} |

||

{{legend|#b56c03| |

{{legend|#b56c03|Rawa gambut dan daerah lanau [[dataran banjir]]<br>(termasuk alur sungai tua dan celah di tepian sungai yang sudah terisi lanau atau gambut)}} |

||

{{legend|#a1aa95| |

{{legend|#a1aa95|Lembah-lembah sungai utama (tidak tertutup gambut)}} |

||

{{legend|#fec901| |

{{legend|#fec901|Gumuk sungai (gumuk [[Pleistosen]])}} |

||

{{legend|#e3f4fc| |

{{legend|#e3f4fc|Perairan terbuka (laut, laguna, sungai)}} |

||

{{legend|#f1f6e2| |

{{legend|#f1f6e2|Bentang alam Pleistosen (> -6 m dibandingkan dengan [[Normaal Amsterdams Peil|NAP]])}} |

||

{{legend|#fffdee| |

{{legend|#fffdee|Bentang alam Pleistosen ( -6 m – 0 m)}} |

||

{{legend|#fff9c2| |

{{legend|#fff9c2|Bentang alam Pleistosen ( 0 m – 10 m)}} |

||

{{legend|#ffeba6| |

{{legend|#ffeba6|Bentang alam Pleistosen ( 10 m – 20 m)}} |

||

{{legend|#fec901| |

{{legend|#fec901|Bentang alam Pleistosen ( 20 m – 50 m)}} |

||

{{legend|#e7a300| |

{{legend|#e7a300|Bentang alam Pleistosen ( 50 m – 100 m)}} |

||

{{legend|#da600d| |

{{legend|#da600d|Bentang alam Pleistosen ( 100 m – 200 m)}} |

||

|} |

|} |

||

=== |

=== Kelompok masyarakat pemburu-peramu tertua (sebelum 5000 SM) === |

||

[[ |

[[Berkas:Mannetje van Willemstad.jpg|jmpl|180px|Arca kecil dari kayu ek setinggi 125 cm (49,2 inci), ditemukan di Willemstad, Negeri Belanda. Diperkirakan dibuat sekitar tahun 4500 SM. Terpajang di [[Rijksmuseum van Oudheden]], Leiden.]] |

||

Kawasan yang kini menjadi [[Belanda|Negeri Belanda]] sudah dihuni manusia purba sekurang-kurangnya pada 37.000 tahun yang lampau, terbukti dari penemuan alat-alat yang terbuat dari [[rijang|batu api]] di [[Woerden]] pada 2010.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.rnw.nl/english/article/neanderthal-may-not-be-oldest-dutchman |title=Neanderthal may not be the oldest Dutchman | Radio Netherlands Worldwide |publisher=Rnw.nl |accessdate=25 Maret 2012}}</ref> Pada 2009, sisa-sisa sebuah tengkorak [[Neanderthal|manusia Neanderthal]] berumur 40.000 tahun ditemukan dalam kegiatan pengerukan pasir dari dasar Laut Utara di perairan lepas pantai Zeeland.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.rnw.nl/english/article/neanderthal-fossil-discovered-zeeland-province |title=Neanderthal fossil discovered in Zeeland province | Radio Netherlands Worldwide |publisher=Rnw.nl |date=16 Juni 2009 |accessdate=25 Maret 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140519074343/http://www.rnw.nl/english/article/neanderthal-fossil-discovered-zeeland-province |archive-date=19 Mei 2014 |dead-url=yes}}</ref> |

|||

Pada Zaman Es terakhir, Negeri Belanda merupakan daerah beriklim [[tundra]] dengan vegetasi yang jarang, dan penduduknya bertahan hidup dengan bermata pencaharian sebagai [[Pemburu-pengumpul|pemburu-peramu]]. Selepas Zaman Es, Negeri Belanda didiami pelbagai kelompok masyarakat berkebudayaan [[paleolitikum|Batu Tua]]. Diketahui bahwa sekitar tahun 8000 SM, sekelompok masyarakat berkebudayaan [[Mesolitikum|Batu Madya]] bermukim di dekat [[Bergumermeer]] ([[Friesland]]). Sekelompok masyarakat yang bermukim di tempat lain diketahui sudah pandai membuat perahu. [[Perahu Pesse]] adalah perahu tertua di dunia yang ditemukan di Negeri Belanda.<ref>{{Citation | last1 = Van Zeist | first1 = W. | title = De steentijd van Nederland | journal=Nieuwe Drentse Volksalmanak | volume = 75 | pages = 4–11 | year = 1957}}</ref><ref name="CMC">{{cite web|url=http://www.civilization.ca/media/docs/pr148beng.html |title=The Mysterious Bog People – Background to the exhibition |publisher=Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation |date=5 Juli 2001 |accessdate=1 Juni 2009 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20070309042811/http://www.civilization.ca/media/docs/pr148beng.html |archivedate=9 Maret 2007 }}</ref> Berdasarkan analisis [[Penanggalan radiokarbon|penentuan umur C14]], perahu ini dibuat pada kurun waktu 8200–7600 SM.<ref name="CMC"/> Perahu Pesse kini terpajang di [[Museum Drents]] di [[Assen]]. |

|||

[[ |

Masyarakat pribumi [[pemburu-pengumpul|pemburu-peramu]] ber[[kebudayaan Swifterbant]] terbukti sudah berdiam di Negeri Belanda sejak sekitar 5600 SM.<ref name=Kooijmans1998>Louwe Kooijmans, L.P., "[https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/handle/1887/1108/171_060.pdf?sequence=1 Trijntje van de Betuweroute, Jachtkampen uit de Steentijd te Hardinxveld-Giessendam]", 1998, ''Spiegel Historiael'' 33, hlmn. 423–428</ref> Kebudayaan ini berkaitan erat dengan sungai-sungai dan perairan terbuka serta masih berkerabat dengan [[kebudayaan Ertebølle]] (5300–4000 SM) di kawasan selatan Skandinavia. Di kawasan barat Negeri Belanda, suku-suku pengusung kebudayaan yang sama boleh jadi sudah mendirikan pondok-pondok perburuan untuk keperluan berburu selama musim dingin, termasuk berburu anjing laut. |

||

=== |

=== Kedatangan budaya bercocok tanam (sekitar 5000–4000 SM) === |

||

Kepandaian bercocok tanam masuk ke Negeri Belanda sekitar 5000 SM bersama [[kebudayaan Tembikar Linear]], yang mungkin dibawa masyarakat-masyarakat tani dari kawasan tengah Eropa. Kegiatan bercocok tanam hanya dilakukan di [[dataran tinggi]] [[löss]] (tanah hasil endapan debu yang terbawa angin) di pelosok selatan Negeri Belanda (kawasan selatan [[Limburg (Belanda)|Limburg]]), namun bahkan di tempat itu pun praktik bercocok tanam tidak bertahan lama. Lahan-lahan usaha tani tidak berkembang di semua daerah lain di Negeri Belanda. |

|||

Agriculture arrived in the Netherlands somewhere around 5000 BC with the [[Linear Pottery culture]], who were probably central European farmers. Agriculture was practised only on the [[loess]] [[plateau]] in the very south (southern [[Limburg (Netherlands)|Limburg]]), but even there it was not established permanently. Farms did not develop in the rest of the Netherlands. |

|||

Ada pula sejumlah jejak keberadaan permukiman-permukiman kecil yang tersebar di seluruh Negeri Belanda. Para pemukim di negeri ini mulai [[peternakan|beternak]] antara 4800 SM dan 4500 SM. Arkeolog Belanda, Leendert Louwe Kooijmans, menulis bahwa "semakin lama semakin jelas bahwasanya transformasi bercocok tanam dari komunitas-komunitas prasejarah merupakan suatu proses yang sepenuhnya alamiah dan berlangsung sangat lamban."<ref name="Kooijmans1998"/> Transformasi ini terjadi seawal-awalnya pada 4300 SM–4000 SM,<ref>Volkskrant 24 Agustus 2007 |

|||

"[http://www.volkskrant.nl/wetenschap/article455140.ece/Prehistorische_akker_gevonden_bij_Swifterbant |

"[http://www.volkskrant.nl/wetenschap/article455140.ece/Prehistorische_akker_gevonden_bij_Swifterbant Lahan bercocok tanam prasejarah ditemukan di Swifterbant, 4300–4000 SM]"</ref> dan melibatkan pengenalan biji-bijian dalam jumlah kecil ke dalam spektrum perekonomian tradisional yang luas.<ref name=Raemakers>Raemakers, Daan. "[http://redes.eldoc.ub.rug.nl/FILES/root/2006/d.raemaekers/Raemaekers.pdf De spiegel van Swifterbant] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080410084410/http://redes.eldoc.ub.rug.nl/FILES/root/2006/d.raemaekers/Raemaekers.pdf |date=10 April 2008 }}", Universitas Groningen, 2006.</ref> |

||

=== |

=== Kebudayaan Bejana Corong dan kebudayaan-kebudayaan lainnya (sekitar 4000–3000 SM) === |

||

[[ |

[[Berkas:Grootste hunebed van Nederl.jpg|jmpl|ka|[[dolmen|Hunebed]] D27, dolmen terbesar di Negeri Belanda, berlokasi di dekat Desa [[Borger, Belanda|Borger]], Provinsi Drenthe.]] |

||

[[Kebudayaan Bejana Corong]] adalah sebuah kebudayaan tani yang berkembang mulai dari Denmark melewati Jerman sampai ke kawasan utara Negeri Belanda. Pada kurun waktu dalam prasejarah Negeri Belanda ini, didirikan peninggalan-peninggalan menonjol yang pertama, yakni [[dolmen|dolmen-dolmen]], monumen-monumen makam dari batu berukuran besar. Dolmen-dolmen ini ditemukan di Provinsi [[Drenthe]], dan mungkin sekali didirikan antara 4100 SM dan 3200 SM. |

|||

The [[Funnelbeaker culture]] was a farming culture extending from Denmark through northern Germany into the northern Netherlands. In this period of Dutch prehistory the first notable remains were erected: the [[dolmens]], large stone grave monuments. They are found in [[Drenthe]], and were probably built between 4100 BC and 3200 BC. |

|||

Di kawasan barat, [[kebudayaan Vlaardingen]] (sekitar 2600 SM), yang tampaknya merupakan sebuah kebudayaan pemburu-peramu yang lebih primitif, terus bertahan hidup sampai memasuki [[neolitikum|Zaman Batu Muda]]. |

|||

To the west, the [[Vlaardingen culture]] (around 2600 BC), an apparently more primitive culture of hunter-gatherers survived well into the [[Neolithic]] period. |

|||

=== |

=== Kebudayaan Gerabah Dawai dan kebudayaan Bejana Genta (sekitar 3000–2000 SM) === |

||

Sekitar 2950 SM, terjadi peralihan dari kebudayaan tani [[kebudayaan Bejana Corong|Bejana Corong]] ke kebudayaan gembala [[kebudayaan Bejana Dawai|Bejana Dawai]], sebuah ruang lingkup arkeologi yang luas muncul di kawasan barat dan tengah Eropa, yang dihubung-hubungkan dengan perkembangan rumpun bahasa India-Eropa. Peralihan ini mungkin sekali merupakan dampak dari perkembangan-perkembangan di kawasan timur Jerman, dan berlangsung dalam dua generasi.<ref name=Bloemers>Dalam J.H.F. Bloemers & T. van Dorp (penyunting), ''Pre- & protohistorie van de lage landen''. De Haan/Open Universiteit, 1991. {{ISBN|90-269-4448-9}}, NUGI 644</ref> |

|||

[[Kebudayaan Bejana Genta]] juga berkembang di Negeri Belanda.<ref name=Lanting>Lanting, J.N. & J.D. van der Waals, (1976), "Beaker culture relations in the Lower Rhine Basin", dalam Lanting dkk. (penyunting) ''Glockenbechersimposion Oberried 1974''. Bussum-Haarlem: Uniehoek N.V.</ref><ref>Hlm. 93, dalam J. P. Mallory dan John Q. Adams (penyunting), ''The Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture'', Fitzroy Dearborn, 1997.</ref> |

|||

Kebudayaan Bejana Dawai dan kebudayaan Bejana Genta bukanlah kebudayaan asli Negeri Belanda namun pada hakikatnya merupakan kebudayaan-kebudayaan lintas Eropa yang berkembang di hampir seluruh kawasan utara dan tengah Eropa. |

|||

The Corded Ware and Bell Beaker cultures were not indigenous to the Netherlands but were pan-European in nature, extending across much of northern and central Europe. |

|||

Bukti pertama penggunaan roda berasal dari kurun waktu ini, yakni sekitar 2400 SM. Kebudayaan ini juga mulai mencoba-coba mengolah tembaga. Bukti-bukti mengenai perkembangan ini meliputi paron-paron batu, pisau-pisau tembaga, dan sebilah mata tombak tembaga yang ditemukan di [[Veluwe]]. Temuan-temuan peralatan tembaga menunjukkan bahwa kala itu sudah ada hubungan dagang dengan kawasan-kawasan lain di Eropa karena tanah Negeri Belanda tidak mengandung tembaga. |

|||

The first evidence of the use of the wheel dates from this period, about 2400 BC. This culture also experimented with working with copper. Evidence of this, including stone anvils, copper knives, and a copper spearhead, was found on the [[Veluwe]]. Copper finds show that there was trade with other areas in Europe, as natural copper is not found in Dutch soil. |

|||

=== |

=== Zaman Perunggu (sekitar 2000–800 SM) === |

||

[[ |

[[Berkas:Zwaard van Jutphaas.jpg|jmpl|ka|80px|Sarana upacara dari perunggu (bukan pedang, namun disebut "Pedang Jutphaas"), diperkirakan berasal dari 1800–1500 SM dan ditemukan di kawasan selatan [[Utrecht]].]] |

||

[[Zaman Perunggu]] mungkin sekali bermula sekitar 2000 SM dan berakhir sekitar 800 SM. Alat-alat [[perunggu]] tertua ditemukan di sebuah makam pribadi dari Zaman Perunggu yang disebut makam "Pandai Logam [[Wageningen]]". Lebih banyak lagi benda Zaman Perunggu dari masa-masa yang lebih kemudian telah ditemukan di [[Epe, Belanda|Epe]], [[Drouwen]], dan daerah-daerah lain. Kepingan benda-benda perunggu yang ditemukan di [[Voorschoten]] tampaknya disiapkan untuk didaur ulang. Kegiatan daur ulang menunjukkan betapa berharganya perunggu bagi masyarakat Zaman Perunggu. Benda-benda perunggu yang lumrah dari kurun waktu ini meliputi pisau, pedang, kapak, [[fibula (peniti)]], dan gelang tangan. |

|||

[[ |

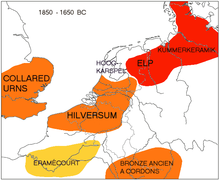

[[Berkas:BronzAgeElp.png|jmpl|kiri|Lokasi [[kebudayaan Elp]] dan [[kebudayaan Hilversum]] pada Zaman Perunggu.]] |

||

Sebagian besar benda peninggalan Zaman Perunggu di Negeri Belanda ditemukan di [[Drenthe]]. Salah satu jenis dari benda-benda peninggalan ini menunjukkan bahwa jaringan dagang pada kurun waktu ini sudah membentang sampai ke tempat-tempat yang jauh, yakni sejumlah ''situlae'' (ember) perunggu berukuran besar hasil temuan di Drenthe yang agaknya dibuat di kawasan timur Prancis atau di [[Swiss]]. Benda-benda ini digunakan sebagai wadah untuk mencampur minuman anggur dengan air (adat Romawi/Yunani). Banyaknya barang temuan di Drenthe yang berupa barang-barang langka dan bernilai tinggi, misalnya beberapa untai kalung manik-manik timah, menyiratkan bahwa Drenthe merupakan sebuah pusat dagang di Negeri Belanda pada Zaman Perunggu. |

|||

Most of the Bronze Age objects found in the Netherlands have been found in [[Drenthe]]. One item shows that trading networks during this period extended a far distance. Large bronze ''situlae'' (buckets) found in Drenthe were manufactured somewhere in eastern France or in [[Switzerland]]. They were used for mixing wine with water (a Roman/Greek custom). The many finds in Drenthe of rare and valuable objects, such as tin-bead necklaces, suggest that Drenthe was a trading centre in the Netherlands in the Bronze Age. |

|||

Masyarakat-masyarakat pribumi ber[[kebudayaan Bejana Genta]] (2700–2100 SM) berkembang menjadi masyarakat-masyarakat berkebudayaan Bejana Kawat Duri (2100–1800 SM). Pada milenium kedua SM, Negeri Belanda merupakan daerah perbatasan antara kawasan ber[[Zaman Perunggu Atlantik|kebudayaan Zaman Perunggu Atlantik]] dan kawasan ber[[Zaman Perunggu Nordik|kebudayaan Zaman Perunggu Nordik]], dan terbagi menjadi wilayah utara dan wilayah selatan yang dipisahkan aliran [[Sungai Rhein]]. |

|||

The [[Beaker culture|Bell Beaker cultures]] (2700–2100) locally developed into the Bronze Age Barbed-Wire Beaker culture (2100–1800). In the second millennium BC, the region was the boundary between the [[Atlantic Bronze Age|Atlantic]] and [[Nordic Bronze Age|Nordic]] horizons and was split into a northern and a southern region, roughly divided by the course of the [[Rhine]]. |

|||

Di wilayah utara, berkembang [[kebudayaan Elp]] (sekitar 1800–800 SM),<ref>Menurut o "Het Archeologisch Basisregister" (ABR), versi 1.0 November 1992, [http://www.racm.nl/content/documenten%5Cabr%20website.pdf], ''Elp Kümmerkeramik'' diberi tarikh BRONSMA (awal MBA) sampai BRONSL (LBA) dan perkiraan tarikh ini telah distandardisasi "De Rijksdienst voor Archeologie, Cultuurlandschap en Monumenten" (RACM)" sebagai kurun waktu yang berawal pada 1800 SM dan berakhir pada 800 SM.</ref> yakni kebudayaan arkeologi Zaman Perunggu yang ditandai pembuatan tembikar [[gerabah]] bermutu rendah yang disebut "''Kümmerkeramik''" (atau "''Grobkeramik''"). Tahap permulaan dari kurun waktu perkembangan kebudayaan Elp bercirikan [[tumulus|tumuli]] atau gundukan-gundukan makam (1800–1200 SM) yang berkaitan erat dengan tumuli semasa di kawasan utara Jerman serta Skandinavia, dan tampaknya masih berkerabat dengan [[kebudayaan Tumulus]] (1600–1200 SM) di kawasan tengah Eropa. Tahap permulaan ini disusul tahap perkembangan berikutnya yang bercirikan adat penguburan [[kebudayaan Padang Tempayan]] atau adat [[kremasi]] (1200–800 SM). Wilayah selatan didominasi [[kebudayaan Hilversum]] (1800–800 M), yang tampaknya mewarisi keterkaitan budaya dengan Britania dari kebudayaan Bejana Kawat Duri sebelumnya. |

|||

== |

== Zaman pra-Romawi (800 SM – 58 SM) == |

||

=== |

=== Zaman Besi === |

||

[[ |

[[Berkas:Boerderij IJzertijd Reijntjesveld.jpg|jmpl|Rekonstruksi tempat tinggal [[Zaman Besi]] di Reijntjesveld, dekat Desa [[Orvelte]], Provinsi [[Drenthe]].]] |

||

[[ |

[[Berkas:Verbogen Keltische zwaard.jpg|jmpl|Pedang besi lengkung asli dari [[Vorstengraf, Oss]], tersimpan di [[Rijksmuseum van Oudheden]].]] |

||

[[Zaman Besi]] mendatangkan kemakmuran bagi masyarakat yang bermukim di Negeri Belanda. Bijih besi terdapat di seluruh pelosok Negeri Belanda, termasuk [[besi rawa gambut]] yang diekstrasi dari [[bijih]] di [[rawa gambut|daerah rawa gambut]] (''moeras ijzererts'') di kawasan utara Negeri Belanda, bola-bola berkandungan besi alami yang ditemukan di [[Veluwe]], dan bijih besi merah dekat sungai-sungai di Brabant. [[tukang besi|Para pandai logam]] berkelana dari satu permukiman kecil ke permukiman kecil lainnya dengan membawa serta [[perunggu]] dan besi untuk ditempa menjadi alat-alat berdasarkan pesanan, yakni kapak, pisau, jarum peniti, mata panah, dan pedang. Beberapa temuan bahkan menyiratkan bahwa para pandai logam ini sudah pandai pula membuat pedang berbahan [[baja Damaskus]] dengan menggunakan metode [[Tempa (metalurgi)|penempaan]] yang sudah lebih maju sehingga mampu memadukan kelenturan besi dengan kekuatan baja. |

|||

The [[Iron Age]] brought a measure of prosperity to the people living in the area of the present-day Netherlands. Iron ore was available throughout the country, including [[bog iron]] extracted from the [[ore]] in [[peat bogs]] (''moeras ijzererts'') in the north, the natural iron-bearing balls found in the [[Veluwe]] and the red iron ore near the rivers in Brabant. [[Blacksmith|Smiths]] travelled from small settlement to settlement with [[bronze]] and iron, fabricating tools on demand, including axes, knives, pins, arrowheads and swords. Some evidence even suggests the making of [[Damascus steel]] swords using an advanced method of [[forging]] that combined the flexibility of iron with the strength of steel. |

|||

Di [[Oss]], sebuah makam yang diperkirakan berasal dari tahun 500 SM ditemukan di dalam sebuah gundukan makam selebar 52 meter (gundukan makam terbesar di kawasan barat Eropa). Makam yang dijuluki "kubur raja" (''[[Vorstengraf, Oss|Vorstengraf]]'') ini berisi benda-benda yang luar biasa, antara lain sebilah pedang besi bertatahkan emas dan batu koral. |

|||

Pada abad-abad menjelang kedatangan bangsa Romawi, wilayah utara yang dahulu dihuni masyarakat berkebudayaan Elp berkembang menjadi masyarakat yang mungkin sekali berkebudayaan Jermanik Harpstedt,<ref name=Mallory>Mallory, J.P., ''In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology and Myth'', London: Thames & Hudson, 1989, hlm. 87.</ref> sementara wilayah selatan dipengaruhi [[kebudayaan Hallstatt]] dan berasimilasi ke dalam kebudayaan Keltik [[kebudayaan La Tène|La Tène]]. Suku-suku rumpun Jermanik yang berpindah ke arah selatan dan barat, serta kebudayaan Hallstatt yang meluas ke arah utara kala itu menarik masyarakat yang bermukim di Negeri Belanda ke dalam ruang lingkup pengaruh mereka.<ref>Butler, J.J., ''Nederland in de bronstijd'', Bussum: Fibula-Van Dishoeck, 1969}}.</ref> Keadaan ini selaras dengan keterangan dalam catatan [[Julius Caesar|Yulius Kaisar]] bahwasanya Sungai Rhein merupakan batas antara wilayah masyarakat Keltik dan wilayah masyarakat Jermanik. |

|||

=== Kedatangan suku-suku rumpun Jermanik === |

|||

===Arrival of Germanic groups=== |

|||

[[ |

[[Berkas:Germanic tribes (750BC-1AD).png|jmpl|kiri|Persebaran suku-suku utama dari rumpun Jermanik ''[[circa|ca.]]'' 1 M.]] |

||

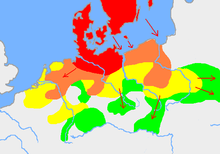

Suku-suku rumpun [[suku bangsa Jermanik|Jermanik]] mula-mula mendiami kawasan selatan [[Skandinavia]], [[Schleswig-Holstein]], dan [[Hamburg]],<ref name="Werner Hilgemann hlm.109">Kinder, Hermann dan Werner Hilgemann, ''The Penguin Atlas of World History''; diterjemahkan Ernest A. Menze ; dengan peta-peta yang dirancang Harald dan Ruth Bukor. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. {{ISBN|0-14-051054-0}} Jilid 1. hlm. 109.</ref> tetapi masyarakat-masyarakat berkebudayaan [[Zaman Besi]] dari kawasan yang sama, seperti masyarakat berkebudayaan [[Wessenstedt]] (800–600 SM) dan masyarakat ber[[kebudayaan Jastorf]], mungkin pula termasuk dalam kelompok ini.<ref>''The New Encyclopaedia Britannica'', edisi ke-15, 20:67</ref> |

|||

Memburuknya iklim di Skandinavia sekitar 850–760 SM yang semakin pesat sekitar 650 SM mungkin memicu perpindahan suku-suku ini. Bukti-bukti arkeologi menyiratkan bahwa pada sekitar 750 SM, [[Belanda|Negeri Belanda]] sampai ke [[Vistula]] dan kawasan selatan Skandinavia didiami masyarakat Jermanik yang relatif seragam.<ref name="Werner Hilgemann hlm.109"/> Di kawasan barat Negeri Belanda, dataran-dataran banjir di daerah pesisir untuk pertama kalinya didiami kaum pendatang baru ini, karena daerah-daerah yang lebih tinggi di sekitarnya sudah mengalami pertambahan populasi dan menjadi lahan tandus.<ref name="Verhart">Verhart, Leo ''Op Zoek naar de Kelten, Nieuwe archeologische ontdekkingen tussen Noordzee en Rijn'', {{ISBN|90-5345-303-2}}, 2006, hlmn. 67, 81–82</ref> |

|||

Ketika proses perpindahan ini rampung sekitar 250 SM, terbentuklah kelompok-kelompok budaya dan bahasa.<ref>''The New Encyclopædia Britannica'', edisi ke-15, 22:641–642</ref><ref name="Verhaal">de Vries, Jan W., Roland Willemyns and Peter Burger, ''Het verhaal van een taal'', Amsterdam: Prometheus, 2003, hlmn. 12, 21–27</ref> |

|||

Kelompok pertama, yang diberi nama masyarakat "[[Jermanik Laut Utara]]", mendiami kawasan utara Negeri Belanda (daerah di sebelah utara sungai-sungai besar) dan menyebar ke seluruh pesisir [[Laut Utara]] sampai ke [[Jutland]]. Kelompok ini kadang-kadang disebut pula masyarakat "[[Ingveon]]", dan mencakup suku-suku yang kemudian hari berkembang menjadi antara lain [[Frisii|orang Frisia purwa]] dan [[bangsa sachsen|orang Saksen purwa]].<ref name="Verhaal"/> |

|||

Kelompok kedua, yang oleh para ahli diberi nama masyarakat "[[Jermanik Weser-Rhein]]" (atau "Jermanik Rhein-Weser"), tersebar di sepanjang kawasan tengah dari daerah aliran Sungai Rhein serta [[Sungai Weser]], dan mendiami kawasan selatan Negeri Belanda (daerah di sebelah selatan sungai-sungai besar). Kelompok ini kadang-kadang disebut pula masyarakat "[[Istveon]]", dan terdiri atas suku-suku yang kemudian hari berkembang menjadi [[orang Franka Sali|suku Franka Sali]].<ref name="Verhaal"/> |

|||

A second grouping, which scholars subsequently dubbed the "[[Weser-Rhine Germanic]]" (or "Rhine-Weser Germanic"), extended along the middle Rhine and [[Weser]] and inhabited the southern part of the Netherlands (south of the great rivers). This group, also sometimes referred to as the "[[Istvaeones]]", consisted of tribes that would eventually develop into the [[Salian Franks]].<ref name="Verhaal"/> |

|||

{{Clear}} |

{{Clear}} |

||

=== Masyarakat Keltik di kawasan selatan Negeri Belanda === |

|||

===Celts in the south=== |

|||

[[File:Celtic expansion in Europe.png| |

[[File:Celtic expansion in Europe.png|jmpl|Persebaran diakronik masyarakat Keltik, menunjukkan perluasan wilayah di kawasan selatan Negeri Belanda: <br /> |

||

{{legend|#ffff43| |

{{legend|#ffff43|Pusat [[kebudayaan Hallstatt]], pada abad ke-6 SM}} |

||

{{legend|#97ffb6| |

{{legend|#97ffb6|Perluasan wilayah maksimal masyarakat Keltik, pada 275 SM}} |

||

{{legend|#b7ffc6|[[Lusitania]] |

{{legend|#b7ffc6|Daerah orang [[Lusitania]] di Iberia, tempat keberadaan masyarakat Keltik tidak dapat dipastikan}} |

||

{{legend|#27c600| |

{{legend|#27c600|daerah-daerah tempat bahasa-bahasa Keltik masih dituturkan secara luas sampai sekarang}}]] |

||

Kebudayaan [[Kelt]]ik berasal dari [[kebudayaan Hallstatt]] (''[[circa|ca.]]'' 800–450 SM) di kawasan tengah Eropa, yakni kebudayaan yang meninggalkan jejak berupa benda-benda bekal kubur yang ditemukan di [[Hallstatt]], Austria.<ref>Cunliffe, Barry. ''The Ancient Celts''. Penguin Books, 1997, hlmn. 39–67.</ref> Kemudian hari, pada kurun waktu perkembangan [[kebudayaan La Tène]] (''ca.'' 450 SM sampai Negeri Belanda ditaklukkan |

|||

bangsa Romawi), kebudayaan Keltik ini, baik melalui [[Difusi lintas budaya|difusi]] maupun [[perpindahan manusia|migrasi]], menyebar luas sampai ke kawasan selatan Negeri Belanda. Kawasan selatan Negeri Belanda ini merupakan batas utara dari daerah persebaran [[Galia|orang Galia]]. |

|||

Pada bulan Maret 2005, 17 keping uang logam Keltik ditemukan di [[Echt, Limburg]]. Kepingan-kepingan uang perak yang bercampur tembaga dan emas ini diperkirakan berasal dari sekitar tahun 50 SM sampai 20 M. Pada bulan Oktober 2008, harta karun berupa 39 keping uang emas dan 70 keping uang perak Keltik ditemukan di daerah [[Amby]], [[Maastricht]].<ref>[http://www.maastricht.nl/maastricht/servlet/nl.gx.maastricht.client.http.GetFile?id=352412&file=Bijlage_-__Unieke_Keltische_muntschat_ontdekt_in_Maastricht.pdf ''Achtergrondinformatie bij de muntschat van Maastricht-Amby''], Kotapraja Maastricht, 2008.</ref> Kepingan-kepingan uang emas diyakini berasal dari masyarakat [[Eburones]].<ref>[http://www.archeonet.be/?p=4289 Unieke Keltische muntschat ontdekt in Maastricht] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120402174540/http://www.archeonet.be/?p=4289 |date=2012-04-02 }}, Archeonet.be, 15 November 2008. Diakses 6 Oktober 2011.</ref> Benda-benda buatan masyarakat Keltik juga telah ditemukan di daerah [[Zutphen]].<ref name="Zutphen">[http://www.zutphen.nl/eCache/16161/urnenveld.pdf ''Het urnenveld van het Meijerink''], Kotapraja Zutphen, Diakses Oktober 20116.</ref> |

|||

Meskipun harta karun sangat jarang ditemukan, pada beberapa dasawarsa terakhir, sejumlah kepingan uang logam dan benda-benda buatan Keltik lainnya telah ditemukan di seluruh kawasan tengah, timur, dan selatan Negeri Belanda. Menurut para arkeolog, barang-barang temuan ini membuktikan bahwa sekurang-kurangnya daerah Lembah Sungai [[Meuse (sungai)|Maas]] di Negeri Belanda termasuk dalam ruang lingkup pengaruh [[kebudayaan La Tène]]. Para arkeolog Belanda bahkan berspekulasi bahwa [[Zutphen]] (yang terletak di kawasan tengah wilayah Negeri Belanda) merupakan daerah permukiman masyarakat Keltik sebelum kedatangan bangsa Romawi, dan sama sekali bukan daerah permukiman masyarakat Jermanik.<ref name="Zutphen"/> |

|||

Although it is rare for hoards to be found, in past decades loose Celtic coins and other objects have been found throughout the central, eastern and southern part of the Netherlands. According to archaeologists these finds confirmed that at least the [[Meuse (river)|Maas]] river valley in the Netherlands was within the influence of the [[La Tène culture]]. Dutch archaeologists even speculate that [[Zutphen]] (which lies in the centre of the country) was a Celtic area before the Romans arrived, not a Germanic one at all.<ref name="Zutphen"/> |

|||

Para ahli berbeda pendapat mengenai luas yang sebenarnya dari ruang lingkup pengaruh budaya Keltik.<ref name="Verhart"/><ref>Delrue, Joke, Universitas Gent</ref> Pengaruh budaya Keltik dan kontak-kontak antara kebudayaan Galia dan kebudayaan Jermani perdana di sepanjang Sungai Rhein diduga sebagai sumber dari sejumlah kata serapan dari bahasa Keltik dalam kosakata [[bahasa proto-Jermanik|bahasa proto Jermanik]]. Namun menurut ahli bahasa berkebangsaan Belgia, Luc van Durme, bukti toponim dari keberadaan masyarakat Keltik di Negeri-Negeri Rendah nyaris tidak ada sama sekali.<ref>van Durme, Luc, "Oude taaltoestanden in en om de Nederlanden. Een reconstructie met de inzichten van M. Gysseling als leidraad" dalam ''Handelingen van de Koninklijke commissie voor Toponymie en Dialectologie'', LXXV/2003.</ref> Meskipun masyarakat Keltik pernah bermukim di Negeri Belanda, inovasi-inovasi Zaman Besi tidak menampakkan pengaruh budaya Keltik yang cukup berarti, dan justru menampakkan hasil pengembangan kebudayaan Zaman Perunggu yang dilakukan masyarakat setempat.<ref name="Verhart"/> |

|||

=== |

=== Teori Blok Barat Laut === |

||

Beberapa orang ahli (De Laet, Gysseling, [[Rolf Hachmann|Hachmann]], Kossack, dan Kuhn) menduga ada masyarakat lain, bukan Jermanik maupun Keltik, yang mendiami Negeri Belanda sampai dengan Zaman Romawi. Ahli-ahli ini berpandangan bahwa Negeri Belanda pada Zaman Besi adalah bagian dari "[[Blok Barat Laut]]" ({{lang-nl|Noordwestblok}}) yang membentang mulai dari Sungai Somme sampai ke Sungai Weser.<ref>Hachmann, Rolf, Georg Kossack and Hans Kuhn, ''Völker zwischen Germanen und Kelten'', 1986, hlmn. 183–212</ref><ref name="Lendering">Lendering, Jona, [http://www.livius.org/ga-gh/germania/inferior.htm "Germania Inferior"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200607071937/https://www.livius.org/ga-gh/germania/inferior.htm |date=2020-06-07 }}, Livius.org. Diakses 6 Oktober 2011.</ref> Menurut pandangan mereka, peradaban yang memiliki bahasa sendiri ini melebur ke dalam [[Kelt|peradaban Keltik]] yang datang dari arah selatan dan peradaban Jermanik yang datang dari arah timur selambat-lambatnya pada Zaman Pra-Romawi. |

|||

== |

== Zaman Romawi (57 SM – 410 M) == |

||

{{utama|Negeri Belanda pada Zaman Romawi}} |

|||

{{Main article|Romans in the Netherlands}} |

|||

=== |

=== Suku-suku pribumi === |

||

Pada masa [[Perang Galia]], wilayah suku-suku [[Belgae|Belgi]] di sebelah selatan [[Oude Rijn (Utrecht dan Belanda Selatan)|Oude Rijn]] dan di sebelah barat [[Sungai Rhein]] ditaklukkan bala tentara Romawi di bawah pimpinan [[Julius Caesar|Yulius Kaisar]] dalam serangkaian aksi militer yang dilancarkan sejak 57 SM sampai 53 SM.<ref name="Lendering"/> Suku-suku yang mendiami Negeri Belanda kala itu tidak meninggalkan keterangan tertulis, sehingga segala informasi mengenai suku-suku ini pada kurun waktu pra-Romawi bersumber dari keterangan yang ditulis orang Yunani dan Romawi mengenai mereka. Salah satu keterangan tertulis semacam ini adalah ''[[Commentarii de Bello Gallico]]'' (Ulasan Perihal Perang Galia) yang ditulis sendiri oleh Yulius Kaisar. Menurut keterangan Yulius Kaisar, dua suku utama penghuni kawasan yang kini menjadi wilayah kedaulatan Negeri Belanda adalah suku [[Menapii]] dan suku [[Eburones]], kedua-duanya bermukin di kawasan selatan Negeri Belanda, yakni kawasan yang diperangi Yulius Kaisar. Yulius Kaisar mencetuskan gagasan bahwa Sungai Rhein adalah pembatas alam antara [[Galia]] dan [[Germania|Germania Magna]]. Akan tetapi Sungai Rhein bukanlah garis perbatasan yang kaku, karena Yulius Kaisar juga menerangkan bahwa sebagian wilayah Galia Belgika didiami banyak suku pribumi (termasuk suku Eburones) yang tergolong suku-suku "[[Germani cisrhenani|''Germani Cisrhenani'']]" (suku-suku Jermanik seberang sini, suku-suku Jermanik di tepi barat Sungai Rhein) atau campuran berbagai suku bangsa yang berbeda-beda asal-usulnya. |

|||

Suku Menapii mendiami wilayah yang membentang dari kawasan selatan Zeeland, melewati [[Brabant Utara]] (dan mungkin sekali [[Holland Selatan]]), sampai ke kawasan tenggara [[Gelderland]]. Pada penghujung Zaman Romawi, wilayah kekuasaan mereka tampaknya terbagi-bagi atau menyusut, sehingga akhirnya hanya meliputi daerah yang kini menjadi kawasan barat negara Belgia. |

|||

Suku [[Eburones]], suku terbesar di antara suku-suku ''Germani Cisrhenani'', mendiami wilayah yang luas termasuk sekurang-kurangnya sebagian dari wilayah [[Limburg (Belanda)|Limburg Belanda]], membentang ke sebelah timur sampai ke [[Sungai Rhein]] di Jerman, dan juga ke sebelah barat laut sampai ke kawasan delta, sehingga berbatasan langsung dengan wilayah kekuasaan suku Menapii. Wilayah kekuasaaan kekuasaan suku Eburones mungkin pula membentang sampai ke Gelderland. |

|||

Mengenai daerah delta itu sendiri, Yulius Kaisar secara sambil lalu mengulas tentang ''Insula Batavorum'' (pulau orang Batavi) di [[Sungai Rhein]], tanpa menjelaskan apa-apa mengenai penghuninya. Kemudian hari, pada zaman Kekaisaran Romawi, suku yang bernama Batavi menjadi suku yang penting di daerah ini.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.02.0001:book=4:chapter=10&highlight=batavi|title=C. Julius Caesar, |

|||

Gallic War, Buku 4, bab 10|website=www.perseus.tufts.edu}}</ref> Kemudian hari, sejarawan [[Tacitus]] mencatat bahwa suku Batavi pada mulanya merupakan salah satu puak suku [[Chatti]], yakni salah satu suku di Jerman yang tidak pernah disebut-sebut Yulius Kaisar.<ref>Cornelius Tacitus, ''Germany and its Tribes'' [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0083%3Achapter%3D29 1.29]</ref> Meskipun demikian, para arkeolog mendapati bukti-bukti adanya peradaban yang berkelanjutan di daerah delta. Oleh karena itu, para arkeolog menduga bahwa mungkin suku Chatti adalah suku kecil yang berpindah ke daerah delta, lalu berbaur dengan masyarakat (mungkin sekali bukan suku rumpun Jermanik) yang sudah lebih dahulu mendiami daerah itu, dan mungkin saja suku Chatti adalah bagian dari suku yang lebih terkenal, misalnya suku Eburones.<ref>Nico Roymans, ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=qfpKN-oMaWoC Ethnic Identity and Imperial Power. The Batavians in the Early Roman Empire]''. Amsterdam Archaeological Studies 10. Amsterdam, 2004. Bab 4. Lihat pula hlm. 249.</ref> |

|||

Gallic War, |

|||

Book 4, chapter 10|website=www.perseus.tufts.edu}}</ref> Much later [[Tacitus]] wrote that they had originally been a tribe of the [[Chatti]], a tribe in Germany never mentioned by Caesar.<ref>Cornelius Tacitus, ''Germany and its Tribes'' [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0083%3Achapter%3D29 1.29]</ref> However, archaeologists find evidence of continuity, and suggest that the Chattic group may have been a small group, moving into a pre-existing (and possibly non-Germanic) people, who could even have been part of a known group such as the Eburones.<ref>Nico Roymans, ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=qfpKN-oMaWoC Ethnic Identity and Imperial Power. The Batavians in the Early Roman Empire]''. Amsterdam Archaeological Studies 10. Amsterdam, 2004. Chapter 4. Also see page 249.</ref> |

|||

{{Gallery |

{{Gallery |

||

|width=250 |height=300 |

|width=250 |height=300 |perrow=2 |

||

|File:Netherlands in time of Caesar.png| |

|File:Netherlands in time of Caesar.png|Suku-suku yang tercatat dalam laporan [[Julius Caesar|Yulius Kaisar]]. |

||

|File:Netherlands in the time of the Roman empire.png| |

|File:Netherlands in the time of the Roman empire.png|Suku-suku pada zaman [[Kekaisaran Romawi]]. |

||

}} |

}} |

||

Kurun waktu [[Romawi Kuno|penjajahan Romawi]] sekitar 450 tahun lamanya menimbulkan perubahan besar di kawasan yang kelak menjadi wilayah kedaulatan Negeri Belanda. Seringkali perubahan itu melibatkan konflik berskala besar antara bangsa Romawi dan suku-suku Jermanik merdeka di sepanjang Sungai Rhein. |

|||

The approximately 450 years of [[Ancient Rome|Roman]] rule that followed would profoundly change the area that would become the Netherlands. Very often this involved large-scale conflict with the free Germanic tribes over the Rhine. |

|||

Suku-suku lain yang pada akhirnya mendiami pulau-pulau di daerah delta pada zaman penjajahan Romawi sebagaimana yang diriwayatkan [[Plinius yang tua|Plinius Tua]] adalah [[orang Kananefati]] di Holland Selatan, [[Frisii|orang Frisi]] di sebagian besar kawasan yang kini menjadi wilayah kedaulatan Negeri Belanda di sebelah utara [[Oude Rijn (Utrecht dan Holland Selatan)|Oude Rijn]]; [[Frisiabones|Orang Frisiaboni]] di kawasan yang membentang mulai dari daerah delta sampai ke sebelah utara Brabant Utara, [[Marsacii|orang Marsaci]] di kawasan yang membentang mulai dari pesisir Vlaanderen sampai ke daerah delta, dan [[Sturii|orang Sturi]].<ref>[http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.02.0137:book=4:chapter=29 Plin. Nat. 4.29]</ref> |

|||

Yulius Kaisar melaporkan bahwa ia telah membinasakan orang Eburoni, namun sebagai gantinya [[Teksuandri|orang Teksuandri]] mendiami sebagian besar daerah Brabant Utara, dan daerah yang sekarang menjadi wilayah provinsi Limburgh, yakni kawasan yang dilewati aliran Sungai Maas dan tampaknya pada zaman Kekaisaran Romawi dihuni (dari utara ke selatan) orang [[Baetasii|orang Betasi]], [[Catualinum|orang Katualini]], [[Sunuci|orang Sunuci]], dan [[Tungri|orang Tungri]] (sejarawan Tacitus melaporkan bahwa Tungri adalah nama baru bagi masyarakat yang sebelumnya disebut orang ''Germani Cisrhenani''). |

|||

Plinius Tua meriwayatkan bahwa di sebelah utara Alter Rhein, selain orang Frisi, ada pula sejumlah [[Chauci|orang Chauci]] yang bermukim sampai ke daerah delta, dan dua suku lain yang diketahui berasal dari kawasan timur Negeri Belanda, yakni [[Tuihanti|orang Tuihanti]] (atau orang Tubanti) dari daerah [[Twenthe]] di Overijssel, dan [[orang Kamavi]] dari [[Hamaland]] di kawasan utara Gelderland, salah satu dari suku-suku pertama yang kelak dinamakan [[orang Franka]]. [[orang Franka Sali|Orang Sali]], yang juga tergolong orang Franka, mungkin berasal dari daerah [[Salland]] di Overijssel, sebelum terpaksa pindah ke wilayah Kekaisaran Romawi akibat rongrongan masyarakat Saksen pada abad ke-4. Mula-mula orang Sali berpindah ke Batavia, kemudian ke Toksandria. |

|||

=== Permukiman-permukiman bangsa Romawi di Negeri Belanda === |

|||

===Roman settlements in the Netherlands=== |

|||

{{multiple image|perrow=2|total_width=350|caption_align=center |

{{multiple image|perrow=2|total_width=350|caption_align=center |

||

| title = |

| title = Permukiman-Permukiman Bangsa Romawi |

||

| image1 = Ruitermasker matilo.jpg|caption1= |

| image1 = Ruitermasker matilo.jpg|caption1=Topeng prajurit berkuda Romawi, ditemukan di dekat kota [[Leiden]]. |

||

| image2 = Germania 70.svg|caption2= |

| image2 = Germania 70.svg|caption2=Perbatasan wilayah [[Kekaisaran Romawi]] di sekitar Sungai Rhein sekitar tahun 70 M. |

||

}} |

}} |

||

Mulai sekitar tahun 15 SM, daerah sekitar [[Sungai Rhein]] di Negeri Belanda menjadi daerah pertahanan [[Limes Germanicus]] Hilir. Setelah berkali-kali dilanda peperangan, Sungai Rhein akhirnya menjadi garis batas utara wilayah kekuasaan bangsa Romawi di daratan Eropa. Sejumlah kota kecil berdiri dan sejumlah perkembangan berlangsung di sepanjang garis batas ini. Daerah di sebelah selatan garis perbatasan diintegrasikan ke dalam [[Kekaisaran Romawi]]. Daerah yang dulunya merupakan wilayah [[Gallia Belgica]] ini dijadikan bagian dari [[provinsi Romawi|provinsi]] [[Germania Inferior]]. The Suku-suku yang sudah lebih dahulu mendiami atau dipindahkan ke daerah ini warga Kekaisaran Romawi. Daerah di sebelah utara Sungai Rhein, yang didiami [[Frisii|orang Frisi]] dan [[Chauci|orang Chauci]], tetap berada di luar pemerintahan Romawi tetapi kerap didatangi dan dikendalikan bangsa Romawi. |

|||

Bangsa Romawi mendirikan benteng-benteng militer di sepanjang [[Limes Germanicus]], berikut sejumlah kota kecil dan permukiman yang lebih kecil lagi di Negeri Belanda. Kota-kota bangsa Romawi yang lebih menonjol berlokasi di [[Nijmegen]] ([[:nl:Ulpia Noviomagus Batavorum|Ulpia Noviomagus Batavorum]]) dan [[Voorburg]] ([[Forum Hadriani]]). |

|||

Mungkin reruntuhan peninggalan bangsa Romawi yang paling menarik adalah puing-puing [[Brittenburg]] yang misterius itu, muncul dari balik pasir pantai di Katwijk beberapa abad yang lalu, hanya untuk dikubur kembali. Puing-puing ini merupakan bagian dari [[:nl:Lugdunum Batavorum|Lugdunum Batavorum]]. |

|||

Bekas-bekas permukiman, benteng kuil, dan bangunan-bangunan bangsa Romawi lainnya telah ditemukan di [[Alphen aan de Rijn]] ([[Albaniana (benteng Romawi)|Albaniana]]), [[Bodegraven]], [[Cuijk]], [[Elst, Overbetuwe|Elst Overbetuwe]], [[Ermelo]], [[Esch, Belanda|Esch]], [[Heerlen]], [[Houten]], [[Kessel, North Brabant|Kessel di Brabant Utara]], [[Oss]] (yakni De Lithse Ham dekat Maren-Kessel), Kesteren di [[Neder-Betuwe]], [[Leiden]] ([[Matilo]]), [[Maastricht]], Meinerswijk (sekarang bagian dari [[Arnhem]]), [[Tiel]], [[Utrecht]] ([[Traiectum (Utrecht)|Traiectum]]), [[Valkenburg (Holland Selatan)|Valkenburg di Holland Selatan]] ([[Praetorium Agrippinae]]), Vechten ([[Fectio]]) sekarang bagian dari [[Bunnik]], [[Velsen]], [[Vleuten]], [[Wijk bij Duurstede]] ([[:nl:Levefanum|Levefanum]]), [[Woerden]] ([[:nl:Laurium (Woerden)|Laurium]] atau [[:nl:Laurium (Woerden)|Laurum]]) dan [[Zwammerdam]] ([[:nl:Nigrum Pullum|Nigrum Pullum]]). |

|||

=== Pemberontakan orang Batavi === |

|||

===Batavian revolt=== |

|||

{{ |

{{utama|Suku Batavi|Pemberontakan orang Batavi}} |

||

[[ |

[[Berkas:"Batavians defeating Romans on the Rhine" by Otto van Veen.jpg|jmpl|Sepanjang sejarah Negeri Belanda, teristimewa semasa [[Perang Delapan Puluh Tahun]], orang Batavi diagung-agungkan sebagai pejuang-pejuang gagah berani yang menjadi cikal bakal bangsa Belanda. "Orang Batavi Mengalahkan Bangsa Romawi di Sungai Rhein", ''ca.'' 1613, karya [[Otto van Veen]].]] |

||

[[ |

[[Berkas:The Conspiracy of Claudius Civilis by Rembrandt van Rijn.jpg|jmpl|''Konspirasi Klaudius Sivilis'', 1661, karya [[Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn|Rembrandt]], menggambarkan peristiwa sumpah setia [[suku batavi|orang Batavi]] kepada [[Gaius Iulius Civilis]], pemimpin [[pemberontakan orang Batavi]] melawan [[Romawi Kuno|penjajah Romawi]] pada tahun 69 M.]] |

||

[[suku Batavi|Orang Batavi]], orang Kananefati, dan suku-suku perbatasan lainnya sangat disegani sebagai prajurit-prajurit tangguh di seluruh wilayah kekaisaran. Menurut tradisi, warga suku-suku ini menjalani masa bakti sebagai prajurit dalam barisan [[Ala (militer Romawi)|pasukan berkuda Romawi]].<ref>Roymans, Nico, ''Ethnic Identity and Imperial Power: The Batavians in the Early Roman Empire'', Amsterdam: Lembaga Pers Universitas Amsterdam, 2005, hlmn. 226–27</ref> Budaya daerah perbatasan dipengaruhi bangsa Romawi, [[suku bangsa Jermanik|suku-suku rumpun Jermanik]], dan masyarakat Galia. Pada abad-abad pertama sesudah Galia ditaklukkan bangsa Romawi, usaha dagang tumbuh subur. Peninggalan-peninggalan budaya bendawi bangsa Romawi, Galia, dan Jermanik ditemukan bercampur baur di kawasan ini. |

|||

Meskipun demikian, orang Batavi memberontak melawan bangsa Romawi dalam peristiwa [[Pemberontakan Batavia]] pada tahun 69 M. Pemimpin [[Pemberotakan orang Batavi|pemberontak]] adalah seorang pribumi Batavi yang bernama [[Gaius Iulius Civilis]]. Salah satu penyebab pemberontakan adalah karena pemuda-pemudi Batavia dijadikan [[perbudakan|budak belian]] oleh bangsa Romawi. Sejumlah ''[[puri|castella]]'' Romawi diserang dan dibakar. Prajurit-prajurit Romawi di [[Xanten]] dan tempat-tempat lain, serta pasukan-pasukan bantu yang beranggotakan orang Batavi dan [[orang Kananefati]] dalam legiun-legiun pimpinan [[Vitellius]] turut bergabung dengan kubu pemberontak, sehingga memecah kesatuan bala tentara Romawi yang bertugas di kawasan utara wilayah kekaisaran. Pada bulan April 70 M, beberapa legiun yang dikerahkan [[Vespasianus]] di bawah pimpinan [[Quintus Petillius Cerialis]] pada akhirnya berhasil mengalahkan orang Batavi dan merundingkan penyerahan diri pemberontak dengan [[Gaius Iulius Civilis]] di suatu tempat yang terletak di daerah antara [[Sungai Waal]] dan [[Sungai Meuse|Sungai Maas]] dekat Noviomagus ([[Nijmegen]]), yang mungkin sekali disebut "Batavodurum" oleh orang Batavi.<ref>[http://classics.mit.edu/Tacitus/histories.html ''Historiae''], Tacitus, 109 M, diterjemahkan Alfred John Church dan William Jackson Brodribb.</ref> Kemudian hari, orang Batavi berbaur dengan suku-suku lain dan menjadi bagian dari [[orang Franka Sali]]. |

|||

Para pujangga Belanda pada abad ke-17 dan ke-18 memandang pemberontakan orang Batavi, yang didorong rasa cinta akan kemerdekaan dan dilakukan demi memerdekakan diri sendiri ini, sebagai aksi yang serupa dengan pemberontakan bangsa Belanda melawan bangsa Spanyol dan segala bentuk lain dari tirani. Menurut pandangan nasionalis ini, [[orang Batavia]] adalah leluhur "sejati" bangsa Belanda. Pandangan semacam inilah yang menyebabkan nama "Batavia" berulang kali dipergunakan bangsa Belanda. [[Jakarta]] dulunya adalah sebuah kota yang diberi nama "Batavia" oleh bangsa Belanda pada tahun 1619. Republik Belanda yang dibentuk pada tahun 1795 berdasarkan prinsip-prinsip revolusioner Prancis disebut [[Republik Batavia]]. Bahkan sekarang ini "orang Batavia" merupakan istilah yang kadang-kadang dipakai sebagai sebutan bagi orang Belanda, sama seperti istilah "orang Galia" dijadikan sebutan bagi orang Prancis dan istilah "orang Teuton" dijadikan sebutan bagi orang Jerman.<ref name="Marnix Beyen 1850">Beyen, Marnix, "A Tribal Trinity: the Rise and Fall of the Franks, the Frisians and the Saxons in the Historical Consciousness of the Netherlands since 1850" in ''European History Quarterly'' 2000 30(4):493–532. {{ISSN|0265-6914}} Fulltext: [[EBSCO]]</ref> |

|||

=== Munculnya orang Franka === |

|||

===Emergence of the Franks=== |

|||

[[ |

[[Berkas:Frankischetalen.png|kiri|jmpl|Peta sebaran orang [[orang Franka Sali|Franka Sali]] (hijau) dan [[orang Franka Ripuari|Franka Ripuari]] (merah) pada akhir era Romawi.]] |

||

Para pengkaji [[periode migrasi]] pada Zaman Modern sepakat bahwa identitas orang Franka muncul pada paruh pertama abad ke-3 dari berbagai kelompok-kelompok kecil masyarakat [[suku bangsa Jermanik|Jermanik]] yang sudah ada sebelumnya, termasuk [[orang Franka Sali|orang Sali]], [[orang Sikambri]], [[orang Kamavi]], [[orang Brukteri]], [[orang Kati]], [[orang Katuari]], [[orang Ampsivari]], [[orang Tenkteri]], [[orang Ubi]], [[orang Batavia|orang Batavi]], dan [[orang Tungri]], yang mendiami bagian hilir dan bagian tengah lembah Sungai Rhein di antara [[Zuyder Zee]] dan [[Sungai Lahn]] serta membentang ke timur sejauh [[Weser]], tetapi lebih banyak bermukim di sekitar [[IJssel]] dan daerah di antara [[Sungai Lippe]] dan [[Sungai Sieg]]. Konfederasi orang Franka mungkin sekali mulai terbentuk pada era 210-an.<ref name="Previté-Orton">Previté-Orton, Charles, ''The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History'', jld. I, hlmn. 51–52, 151</ref> |

|||

Orang Franka pada akhirnya terbagi menjadi dua kelompok, yakni [[orang Franka Ripuari]] ({{lang-la|Ripuari}}) yang mendiami daerah tengah lembah Sungai Rhein pada zaman penjajahan Romawi, dan [[orang Franka Sali]] yang berasal dari Negeri Belanda. |

|||

The Franks eventually were divided into two groups: the [[Ripuarian Franks]] (Latin: Ripuari), who were the Franks that lived along the middle-Rhine River during the Roman Era, and the [[Salian Franks]], who were the Franks that originated in the area of the Netherlands. |

|||

Orang Franka dicatat sebagai kawan maupun lawan (''[[laeti]]'' maupun ''dediticii'') dalam karya-karya tulis Romawi. Sekitar tahun 320, orang Franka berhasil menguasai daerah sekitar Sungai [[Scheldt]] (sekarang menjadi daerah Vlaanderen Barat dan kawasan barat daya Negeri Belanda), dan melakukan perompakan di [[Selat Inggris]], menghambat kelancaran angkutan laut menuju [[Britania Romawi|Britania]]. Pasukan-pasukan Romawi dapat mengamankan kawasan itu, tetapi tidak mengusir orang Franka, yang tetap saja ditakuti sebagai gerombolan perompak di sepanjang daerah pesisir setidaknya sampai masa pemerintahan [[Flavius Claudius Julianus|Yulianus Si Murtad]] (358), yakni masa ketika [[orang Franka Sali]] diizinkan menetap di [[Toksandria]] sebagai salah satu ''[[foederatus|foederati]]'' Kekaisaran Romawi, menurut keterangan [[Ammianus Marcellinus]].<ref name="Previté-Orton"/> |

|||

=== Lenyapnya orang Frisi === |

|||

===Disappearance of the Frisii=== |

|||

[[ |

[[Berkas:North.Sea.Periphery.250.500.jpg|jmpl|200px|ka|Kawasan sekitar [[Laut Utara]] ''ca.'' 250-500 M.]] |

||

Ada tiga faktor yang menyebabkan [[Frisii|orang Frisi]] menghilang dari kawasan utara Negeri Belanda. Yang pertama, menurut ''[[Panegyrici Latini]]'' (Naskah VIII), [[Frisii|orang Frisi]] kuno dipaksa pindah ke permukiman baru di dalam wilayah Kekaisaran Romawi sebagai ''[[laeti]]'' (kaum [[serf|hamba tani]] Romawi) sekitar tahun 296.<ref>{{Citation |

|||

|last=Grane |

|last=Grane |

||

|first=Thomas |

|first=Thomas |

||

| Baris 202: | Baris 201: | ||

|contribution=From Gallienus to Probus – Three decades of turmoil and recovery |

|contribution=From Gallienus to Probus – Three decades of turmoil and recovery |

||

|title=The Roman Empire and Southern Scandinavia–a Northern Connection! (PhD thesis) |

|title=The Roman Empire and Southern Scandinavia–a Northern Connection! (PhD thesis) |

||

|publisher= |

|publisher=Universitas Copenhagen |

||

|publication-date=2007 |

|publication-date=2007 |

||

|publication-place=Copenhagen |

|publication-place=Copenhagen |

||

|page=109 |

|page=109 |

||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> Keterangan ini adalah kabar paling akhir mengenai [[Frisii|orang Frisi]] dalam catatan sejarah. Nasib mereka selanjutnya hanya dapat diduga melalui catatan arkeologi. Penemuan sejenis gerabah khas [[Frisia]] dari abad ke-4, yang disebut ''terp Tritzum'', menyiratkan bahwa orang-orang Frisi, dalam jumlah yang tidak diketahui, berpindah ke [[Flandria|Vlaanderen]] dan [[Kent]],<ref>{{Citation |

||

|last=Looijenga |

|last=Looijenga |

||

|first=Jantina Helena |

|first=Jantina Helena |

||

| Baris 212: | Baris 211: | ||

|editor-last=SSG Uitgeverij |

|editor-last=SSG Uitgeverij |

||

|contribution=History, Archaeology and Runes |

|contribution=History, Archaeology and Runes |

||

|title=Runes Around the North Sea and on the Continent AD 150–700; Texts and Contexts ( |

|title=Runes Around the North Sea and on the Continent AD 150–700; Texts and Contexts (disertasi PhD) |

||

|publisher= |

|publisher=Universitas Groningen |

||

|publication-date=1997 |

|publication-date=1997 |

||

|publication-place=Groningen |

|publication-place=Groningen |

||

|page=30 |

|page=30 |

||

|isbn=90-6781-014-2 |

|isbn=90-6781-014-2 |

||

|url=http://dissertations.ub.rug.nl/FILES/faculties/arts/1997/j.h.looijenga/thesis.pdf |

|url=http://dissertations.ub.rug.nl/FILES/faculties/arts/1997/j.h.looijenga/thesis.pdf |

||

|accessdate=2018-08-09 |

|||

Second, the environment in the low-lying coastal regions of northwestern Europe began to lower c. 250 and gradually receded over the next 200 years. Tectonic [[subsidence]], a rising [[water table]] and [[storm surge]]s combined to flood some areas with [[marine transgression]]s. This was accelerated by a shift to a cooler, wetter climate in the region. If there had been any [[Frisii]] left in Frisia, they would have drowned.<ref name="Berglund 2002 10">{{Citation |

|||

|archive-date=2005-05-02 |

|||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050502101056/http://dissertations.ub.rug.nl/FILES/faculties/arts/1997/j.h.looijenga/thesis.pdf |

|||

|dead-url=yes |

|||

}}. Untuk kesimpulan ini, Looijenga mengutip D.A. Gerrets (1995), "The Anglo-Frisian Relationship Seen from an Archaeological Point of View" dalam ''Friesische studien'' 2, hlmn. 119–128.</ref> agaknya sebagai ''laeti'' di bawah paksaan bangsa Romawi. |

|||

Yang kedua, lingkungan daerah pesisir yang rendah di kawasan barat laut Eropa mulai semakin amblas sekitar tahun 250, dan perlahan-lahan terhenti sepanjang 200 tahun berikutnya. [[Subsiden tanah|Subsidensi]] tektonik, naiknya [[permukaan air tanah]], dan [[pusuan ribut]] mengakibatkan sejumlah daerah terendam [[transgresi laut]]. Keadaan ini semakin diperparah perubahan iklim di daerah pesisir sehingga menjadi lebih dingin dan lebih lembap. Andaikata masih ada [[Frisii|orang Frisi]] yang tersisa di daerah pesisir, tentunya mereka punah akibat tenggelam.<ref name="Berglund 2002 10">{{Citation |

|||

|last=Berglund |

|last=Berglund |

||

|first=Björn E. |

|first=Björn E. |

||

| Baris 251: | Baris 255: | ||

|contribution= |

|contribution= |

||

|title=Climate Changes during the Holocene and their Impact on Hydrological Systems |

|title=Climate Changes during the Holocene and their Impact on Hydrological Systems |

||

|publisher= |

|publisher=Universitas Cambridge |

||

|publication-date=2003 |

|publication-date=2003 |

||

|publication-place=Cambridge |

|publication-place=Cambridge |

||

| Baris 260: | Baris 264: | ||

|year=1974 |

|year=1974 |

||

|contribution= |

|contribution= |

||

|title=The Rhine/Meuse Delta. Four studies on its prehistoric occupation and Holocene geology ( |

|title=The Rhine/Meuse Delta. Four studies on its prehistoric occupation and Holocene geology (disertasi PhD) |

||

|publisher= |

|publisher=Lembaga Pers Universitas Leiden |

||

|publication-date=1974 |

|publication-date=1974 |

||

|publication-place=Leiden |

|publication-place=Leiden |

||

|url=http://hdl.handle.net/1887/2787 |

|url=http://hdl.handle.net/1887/2787 |

||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> |

||

Yang ketiga, selepas runtuhnya Kekaisaran Romawi, terjadi penurunan jumlah penduduk seiring terhentinya akitivitas bangsa Romawi dan penarikan mundur lembaga-lembaga bangsa Romawi. Sebagai akibat dari ketiga faktor ini, [[Frisii|orang Frisi]] dan [[Frisii|orang Frisievoni]] menghilang dari daerah bekas permukiman asli mereka. Sebagian besar daerah pesisir tetap tidak berpenghuni selama dua abad selanjutnya.<ref name="Berglund 2002 10"/><ref name="Ejstrud"/><ref name="Issar 2003"/><ref name="Louwe"/> |

|||

== |

== Abad Pertengahan Awal (411–1000) == |

||

=== |

=== Orang Frisia === |

||

{{ |

{{Utama|Kerajaan orang Frisia|Dorestad}} |

||

[[ |

[[Berkas:Frisia 716-la.svg|jmpl|kiri|Perkiraan kasar persebaran orang Franka dan orang Frisia sekitar tahun 716 M]] |

||

Seiring membaiknya keadaan iklim, suku-suku rumpun Jermanik sekali lagi beramai-ramai hijrah meninggalkan kampung halaman mereka di sebelah timur menuju tempat-tempat lain. Kurun waktu berlangsungnya migrasi besar-besaran ini dikenal dengan sebutan "[[Zaman Migrasi]]" (''Volksverhuizingen''). Kawasan utara Negeri Belanda dibanjiri kaum pendatang, yakni [[orang Anglia]], [[orang Yuti]], dan terutama [[orang Saksen]]. Banyak di antara kaum pendatang ini tidak menetap di kawasan utara Negeri Belanda tetapi terus bergerak menuju Inggris, dan kini dikenal dengan sebutan [[orang Anglia-Sachsen]]. Kaum pendatang yang tidak melanjutkan perjalanan menuju Inggris kelak dikenal dengan sebutan "orang Frisia", sekalipun bukan keturunan [[Frisii|orang Frisi]]. Para warga Frisia yang baru ini menetap di kawasan utara Negeri Belanda, dan menjadi cikal bakal [[bangsa Frisia]] modern.<ref>{{Citation |

|||

As climatic conditions improved, there was another mass migration of [[Germanic tribes|Germanic]] peoples into the area from the east. This is known as the "[[Migration Period]]" (''Volksverhuizingen''). The northern Netherlands received an influx of new migrants and settlers, mostly [[Saxons]], but also [[Angles]] and [[Jutes]]. Many of these migrants did not stay in the northern Netherlands but moved on to England and are known today as the [[Anglo-Saxons]]. The newcomers who stayed in the northern Netherlands would eventually be referred to as "Frisians", although they were not descended from the ancient [[Frisii]]. These new Frisians settled in the northern Netherlands and would become the ancestors of the modern [[Frisians]].<ref>{{Citation |

|||

|last=Bazelmans |

|last=Bazelmans |

||

|first=Jos |

|first=Jos |

||

| Baris 284: | Baris 288: | ||

|contribution-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fM_cmuhmSbIC&pg=PA321 |

|contribution-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fM_cmuhmSbIC&pg=PA321 |

||

|title=Ethnic Constructs in Antiquity: The Role of Power and Tradition |

|title=Ethnic Constructs in Antiquity: The Role of Power and Tradition |

||

|publisher= |

|publisher=Universitas Amsterdam |

||

|publication-date=2009 |

|publication-date=2009 |

||

|publication-place=Amsterdam |

|publication-place=Amsterdam |

||

|pages= |

|pages=321–337 |

||

|isbn=978-90-8964-078-9 |

|isbn=978-90-8964-078-9 |

||

|url=http://s393993344.online.de/ssoar/handle/document/27183 |

|url=http://s393993344.online.de/ssoar/handle/document/27183 |

||

|accessdate=2018-08-09 |

|||

}}</ref><ref>[http://www.bertsgeschiedenissite.nl/ijzertijd/eeuw1ac/frisii.html Frisii en Frisiaevones, 25–08–02 (Dutch)] {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111003101550/http://www.bertsgeschiedenissite.nl/ijzertijd/eeuw1ac/frisii.html |date=3 October 2011 }}, Bertsgeschiedenissite.nl. Retrieved 6 October 2011</ref> (Because the early [[Frisians]] and [[Anglo-Saxons]] were formed from largely identical tribal confederacies, their respective languages were very similar. [[Old Frisian]] is the most closely related language to [[Old English]]<ref>{{cite web|url=https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/1887/1937/1/344_121.pdf |title=The origin of the Old English dialects revisited|first=Frederik |last=Kortlandt |year=1999|publisher=[[University of Leiden]]}}</ref> and the modern Frisian dialects are in turn the closest related languages to contemporary English.) By the end of the 6th century, the Frisian territory in the northern Netherlands had expanded west to the [[North Sea]] coast and, by the 7th century, south to [[Dorestad]]. During this period most of the northern Netherlands was known as [[Frisia]]. This extended Frisian territory is sometimes referred to as ''[[Frisian Kingdom|Frisia Magna]]'' (or [[Greater Frisia]]). |

|||

|archive-date=2017-08-30 |

|||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170830194912/http://s393993344.online.de/ssoar/handle/document/27183 |

|||

|dead-url=yes |

|||

}}</ref><ref>[http://www.bertsgeschiedenissite.nl/ijzertijd/eeuw1ac/frisii.html Frisii en Frisiaevones, 25–08–02 (bahasa Belanda)] {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111003101550/http://www.bertsgeschiedenissite.nl/ijzertijd/eeuw1ac/frisii.html |date=3 Oktober 2011 }}, Bertsgeschiedenissite.nl. Diakses 6 Oktober 2011</ref> [[Orang Frisia]] maupun [[orang Anglia-Sachsen]] terdahulu lahir dari konfederasi-konfederasi kesukuan yang identik, sehingga bahasanya pun sangat mirip. [[bahasa Frisia Lama]] berkerabat dekat dengan [[bahasa Inggris Lama]],<ref>{{cite web|url=https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/1887/1937/1/344_121.pdf |title=The origin of the Old English dialects revisited|first=Frederik |last=Kortlandt |year=1999|publisher=[[Universitas Leiden]]}}</ref> sehingga dialek-dialek bahasa Frisia modern pun pada gilirannya berkerabat dekat dengan bahasa Inggris modern. Pada akhir abad ke-6, daerah kekuasaan orang Frisia di kawasan utara Negeri Belanda telah meluas sampai ke daerah pesisir [[Laut Utara]], dan meluas sampai ke [[Dorestad]] di sebelah selatan pada abad ke-7. Selama kurun waktu ini, sebagian besar kawasan utara Negeri Belanda dikenal dengan sebutan [[Frisia]]. Daerah kekuasaan orang Frisia yang sangat luas ini adakalanya juga disebut ''[[Kerajaan orang Frisia|Frisia Magna]]'' atau [[Frisia Raya]]. |

|||

[[ |

[[Berkas:Dorestad and trade routes.jpg|jmpl|[[Dorestad]] dan jalur-jalur dagang utama |

||

]] |

|||

In the 7th and 8th centuries, the [[Franks|Frankish]] chronologies mention this area as the [[Frisian Kingdom|kingdom of the Frisians]]. This kingdom comprised the coastal provinces of the [[Netherlands]] and the German [[North Sea]] coast. During this time, the Frisian language was spoken along the entire southern North Sea coast. The 7th-century [[Frisian Kingdom]] (650–734) under King [[Aldegisel]] and King [[Redbad, King of the Frisians|Redbad]], had its centre of power in [[Utrecht (city)|Utrecht]]. |

|||

Pada abad ke-7 dan ke-8, daerah ini disebut-sebut dalam catatan sejarah [[orang Franka]] sebagai [[kerajaan orang Frisia]]. Wilayah kerajaan ini meliputi provinsi-provinsi yang terletak di daerah pesisir Negeri Belanda dan daerah pesisir [[Laut Utara]] Jerman. Pada kurun waktu ini, bahasa Frisia dipertuturkan di seluruh kawasan selatan daerah pesisir Laut Utara. Pada abad ke-7, [[kerajaan orang Frisia]] (650–734) di bawah pemerintahan Raja [[Aldegisel]] dan Raja [[Redbad, raja orang Frisia|Redbad]] berpusat di [[Utrecht (kota)|kota Utrecht]]. |

|||

[[Dorestad]] |

[[Dorestad]] adalah pekan ([[Emporium (Abad Pertengahan Awal)|emporium]]) terbesar di kawasan barat laut Eropa, yang berkembang di sekitar sebuah bekas benteng Romawi. Pekan ini adalah tempat berdagang yang ramai, tiga kilometer panjangnya, dan terletak di daerah tempat aliran [[Sungai Rhein]] dan [[Sungai Lek]] berbelok ke sebelah tenggara kota [[Utrecht (kota)|Utrecht]], tak jauh dari kota [[Wijk bij Duurstede]] modern.<ref>Willemsen, A. (2009), ''Dorestad. Een wereldstad in de middeleeuwen,'' Walburg Pers, Zutphen, pp. 23–27, {{ISBN|978-90-5730-627-3}}</ref><ref name="Atlas">{{cite book | title=Atlas of Medieval Europe| url=https://books.google.com/?id=q50IyzCMQxgC&pg=PA57&lpg=PA57&dq=dorestad#PPA57,M1| last=MacKay| first=Angus|author2=David Ditchburn| year=1997| page=57| publisher=[[Routledge]]| isbn=0-415-01923-0}}</ref> Sekalipun terletak jauh dari pesisir, Dorestad merupakan pusat dagang di kawasan Laut Utara yang banyak memperjualbelikan barang-barang dari [[Rheinland]] Tengah.<ref name="Atlas"/><ref name="MC&OE">{{cite book | title=Mohammed, Charlemagne and the Origins of Europe| url=https://books.google.com/?id=6utbT529jLcC&pg=PA99&lpg=PA99&dq=dorestad#PPA99,M1| last=Hodges| first=Richard|author2=David Whitehouse| year=1983| page=99| publisher=Lembaga Pers Universitas Cornell| isbn=978-0-8014-9262-4}}</ref> Salah satu barang dagangan utama yang diperjualbelikan di Dorestad adalah minuman anggur, yang agaknya didatangkan dari kebun-kebun anggur di sebelah selatan [[Mainz]].<ref name="MC&OE"/> Dorestad juga terkenal karena [[percetakan uang logam]]nya. Antara tahun 600 sampai kira-kira tahun 719, Dorestad berulang kali diperebutkan [[bangsa Frisia|orang Frisia]] dan [[orang Franka]]. |

||

=== |

=== Orang Franka === |

||

{{utama|Orang Franka|Orang Franka Sali}} |

|||

{{Main article|Franks|Salian Franks}} |

|||

[[ |

[[Berkas:Franks expansion.gif|jmpl|kiri|Gerak ekspansi [[orang Franka]] dari tahun 481 sampai tahun 870 M]] |

||

Setelah pemerintahan [[Kekaisaran Romawi|Romawi]] di kawasan ini runtuh, [[orang Franka]] bergerak memperluas daerah kekuasaan mereka sampai sehingga tumbuh banyak kerajaan kecil bentukan orang Franka, terutama di [[Köln]], [[Tournai|Doornik]], [[Le Mans]], dan [[Cambrai|Kamerijk]].<ref name="Previté-Orton"/><ref name="Milis, L.J.R. hlmn. 6-18">Milis, L.J.R., "A Long Beginning: The Low Countries Through the Tenth Century" dalam J.C.H. Blom & E. Lamberts ''History of the Low Countries'', hlmn. 6–18, Berghahn Books, 1999. {{ISBN|978-1-84545-272-8}}.</ref> Raja-raja Doornik akhirnya menundukkan raja-raja orang Franka lainnya. Pada kurun waktu 490-an, [[Clovis I|Klovis I]] berhasil menundukkan dan mempersatukan seluruh daerah kekuasaan orang Franka di sebelah barat [[Meuse (sungai)|Sungai Maas]], termasuk kerajaan-kerajaan orang Franka di kawasan selatan Negeri Belanda. Klovis kemudian meneruskan aksi penaklukannya ke wilayah [[Galia]]. |

|||

Setelah [[Clovis I|Klovis I]] wafat pada tahun 511, keempat putranya membagi-bagi wilayah kerajaannya. [[Thierry I|Theuderik I]] mendapatkan daerah-daerah yang kelak menjadi wilayah Kerajaan Austrasia (termasuk kawasan selatan Negeri Belanda). Anak dan cucu Theuderik I berturut-turut memerintah menggantikannya sampai Kerajaan [[Austrasia]] dipersatukan dengan kerajaan-kerajaan orang Franka lainnya pada tahun 555 oleh [[Clotaire I|Klothar I]], yang menjadi penguasa tunggal atas seluruh wilayah kekuasaan orang Franka pada tahun 558. Klothar I membagi-bagikan wilayah kerajaannya kepada keempat putranya, tetapi keempat wilayah hasil pembagian ini berubah menjadi tiga kerajaan saja sepeninggal [[Caribert I|Karibert I]] pada tahun 567. Kerajaan Austrasia (termasuk kawasan selatan Negeri Belanda) diberikan kepada [[Sigebert I]]. Kawasan selatan Negeri Belanda seterusnya menjadi bagian dari wilayah Kerajaan [[Austrasia]] until sampai pada masa pemerintahan [[wangsa Karoling]]. |

|||

After the death of [[Clovis I]] in 511, his four sons partitioned his kingdom amongst themselves, with [[Theuderic I of Austrasia|Theuderic I]] receiving the lands that were to become Austrasia (including the southern Netherlands). A line of kings descended from Theuderic ruled [[Austrasia]] until 555, when it was united with the other Frankish kingdoms of [[Chlothar I]], who inherited all the Frankish realms by 558. He redivided the Frankish territory amongst his four sons, but the four kingdoms coalesced into three on the death of [[Charibert I]] in 567. Austrasia (including the southern Netherlands) was given to [[Sigebert I]]. The southern Netherlands remained the northern part of [[Austrasia]] until the rise of the [[Carolingians]]. |

|||

Orang-orang Franka yang berekspansi sampai ke [[Galia]] akhirnya menetap dan mengadopsi [[bahasa Latin Umum]] yang dituturkan masyarakat setempat.<ref name="Verhaal"/> Meskipun demikian, bahasa Jermanik masih tetap digunakan sebagai bahasa kedua oleh para pejabat publik di kawasan barat [[Austrasia]] dan [[Neustria]] sampai kurun waktu 850-an. Bahasa Jermanik punah di daerah-daerah ini pada abad ke-10.<ref>[[Urban T. Holmes Jr.|Holmes, U.T]] dan A. H. Schutz (1938), ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=jbjX4ebc2lsC&printsec=frontcover&dq=history+of+french+language&hl=en&ei=jRjOTtqdDNPR4QTr1pQ8&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CDMQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=history%20of%20french%20language&f=false A History of the French Language]'', hlm. 29, Biblo & Tannen Publishers, {{ISBN|0-8196-0191-8}}</ref> Pada masa ekspansi ke Galia, banyak puak orang Franka yang tetap tinggal di utara (yakni di kawasan selatan Negeri Belanda, Vlaanderen, dan sebagian kecil kawasan utara Prancis). Muncul kesenjangan budaya yang kian melebar antara masyarakat Franka yang tetap tinggal di utara dan para pemimpin Franka di Galia, yakni di kawasan yang sekarang menjadi wilayah negara Prancis.<ref name="Milis, L.J.R. hlmn. 6-18"/> Orang Franka Sali tetap tinggal di kampung halaman aslinya dan di daerah-daerah tetangga di sebelah selatan serta tetap menuturkan bahasa aslinya, [[bahasa Franka Lama]], yang berkembang menjadi [[bahasa Belanda Lama]] pada abad ke-9.<ref name="Verhaal"/> Garis batas antara wilayah penutur bahasa Belanda dan wilayah penutur bahasa Prancis akhirnya terbentuk, tetapi mula-mula jauh lebih ke selatan dari letaknya saat ini.<ref name="Verhaal"/><ref name="Milis, L.J.R. hlmn. 6-18"/> Di daerah-daerah yang dilewati Sungai Maas dan Sungai Rhein di Negeri Belanda, orang Franka menguasai pusat-pusat politik dan perdagangan, khususnya di [[Nijmegen]] dan [[Maastricht]].<ref name="Milis, L.J.R. hlmn. 6-18"/> Orang-orang Franka di daerah ini masih tetap berhubungan dengan orang Frisia di utara, terutama di tempat-tempat seperti [[Dorestad]] dan [[Utrecht]]. |

|||

=== Keraguan pada Zaman Modern mengenai perbedaan antara orang Frisia, orang Franka, dan orang Saksen === |

|||