Bahasa Yunani Koine Yahudi

| Bahasa Yunani Koine Yahudi | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

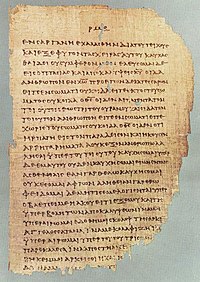

Papirus 46 adalah salah satu naskah Perjanjian Baru tertua yang masih ada dalam bahasa Yunani, ditulis di atas papirus, kemungkinan ditulis antara tahun 175 dan 225 | |||||||||||

| Wilayah | Timur Tengah | ||||||||||

| Era | abad ke-2 SM hingga ke-7 M[1] | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Alfabet Yunani dan Abjad Ibrani | |||||||||||

| Kode bahasa | |||||||||||

| ISO 639-2 | grc | ||||||||||

| ISO 639-3 | – (ecg diusulkan) | ||||||||||

LINGUIST List | grc-koi | ||||||||||

| Glottolog | Tidak ada | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Bahasa Yunani Koine Yahudi adalah ragam bahasa Yunani Koine yang ditemukan dalam sejumlah naskah Yahudi Helenistik, terutama dalam terjemahan Septuaginta dari Alkitab Ibrani dan sastra terkait, serta dalam naskah tradisi Yahudi Yunani dari Palestina. Istilah ini sebagian besar setara dengan bahasa Yunani di Septuaginta sebagai kategori budaya dan sastra ketimbang kategori linguistik. Sintaksis kecil dan variasi kosa kata dalam bahasa Yunani Koine dari penulis Yahudi tidak berbeda secara linguistik seperti bahasa turunannya seperti bahasa Yunani Romaniot yang dituturkan oleh kaum Yahudi Romaniot di Yunani.[4]

Sejarah kepustakaan

[sunting | sunting sumber]Karya ilmiah utama di bidang ini dilakukan oleh para cendekiawan seperti Henry Barclay Swete dalam bab 4 Introduction to the Old Testament in Greek.[5] Namun, penekanan Swete pada kekhasan bahasa Yunani Septuaginta dibandingkan dengan teks-teks Yunani lainnya pada periode tersebut sebagian besar telah ditarik kembali oleh para sarjana kemudian karena banyak papirus dan prasasti Koine domestik dan administrasi non-Yahudi telah ditemukan dan dipelajari dengan lebih baik. Sejak Swete menyamakan bahasa Yahudi Koine dengan "bahasa Yunani di Septuaginta" juga telah diperluas, menempatkan Septuaginta dalam konteks berbagai teks Yahudi pada periode tersebut, yang terakhir memasukkan teks Yunani di antara Naskah Laut Mati.[6]

Tidak ada penulis kuno atau abad pertengahan yang mengenali dialek Yunani Yahudi yang berbeda.[7] Konsensus akademik umum adalah bahwa bahasa Yunani yang digunakan dalam naskah Yunani Koine Yahudi tidak cukup berbeda secara dari naskah Yunani Koine non-Yahudi. Hal tersebut juga berlaku untuk bahasa dalam Perjanjian Baru.[8][9][10][11] Karena pengaruh dominan Septuaginta, naskah-naskah pertama "Yunani Kristen" dan "Yunani Patristik" awal keduanya merupakan perpanjangan dari bahasa Yunani Klasik di satu sisi, dan bahasa Yunani Alkitabiah dan Yunani Yahudi Hellenistik di sisi lain.[12][13]

Hanya seribu tahun kemudian muncul dialek Yahudi Yunani yang sebenarnya, Romaniot.[14][15]

Tata bahasa

[sunting | sunting sumber]Tata bahasa Yunani Koine sudah menyimpang dari tata bahasa Yunani Kuno di beberapa wilayah, tetapi naskah-naskah Yahudi umumnya konsisten dengan naskah non-Yahudi, dengan pengecualian sejumlah kecil semitisme tata bahasa.[16] Seperti yang diharapkan banyak teks Yahudi menunjukkan hampir tidak ada penyimpangan dari Koine atau "Attika Umum" yang digunakan oleh penulis non-Yahudi. Para penulis yang menulis untuk pembaca non-Yahudi seperti Yosefus dan Filo mengamati kaidah tata bahasa Yunani jauh di atas banyak sumber pagan yang bertahan.

Neologisme

[sunting | sunting sumber]Perbedaan utama antara Septuaginta, dan sastra terkait, dan teks Koine non-Yahudi kontemporer adalah adanya sejumlah neologisme (istilah baru) atau penggunaan kosa kata baru.[17][18][19] Namun, hapax legomena mungkin tidak selalu menunjukkan neologisme, mengingat pokok bahasan khusus dari Septuaginta.[20] Juga beberapa "neologisme" dari Septuaginta bukanlah istilah yang sama sekali baru dan mungkin merupakan perpaduan dari istilah-istilah yang ada seperti fenomena Neubildungen dalam bahasa Jerman, seperti sejumlah besar kata majemuk yang mewakili dua atau lebih kata Ibrani.[21]

Contoh

[sunting | sunting sumber]- Ioudaizein (Ἰουδαΐζειν): "mengyahudikan" atau "yahudisasi" (lihat Yudaiser dan Galatia 2:14)

- sabbatizo (σαββατίζω): "Aku memelihara hari Sabat"

- pseudoprophetes (ψευδοπροφήτης): "nabi palsu" (naskah-naskah klasik menggunakan ψευδόμαντις pseudomantis)

Lihat pula

[sunting | sunting sumber]Referensi

[sunting | sunting sumber]- ^ Ross, William A. (15 November 2021). "The Most Important Bible Translation You've Never Heard Of". Articles. Scottsdale, Arizona: Text & Canon Institute of the Phoenix Seminary. Diakses tanggal 25 December 2022.

- ^ "UNESCO Interactive Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger" (dalam bahasa bahasa Inggris, Prancis, Spanyol, Rusia, and Tionghoa). UNESCO. 2011. Diarsipkan dari versi asli tanggal 29 April 2022. Diakses tanggal 26 Juni 2011.

- ^ "UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger" (PDF) (dalam bahasa Inggris). UNESCO. 2010. Diarsipkan dari versi asli (PDF) tanggal 31 Mei 2022. Diakses tanggal 31 Mei 2022.

- ^ Matthew Kraus How should rabbinic literature be read in the modern world? 2006, page 214. "It is suggestive of a “Jewish koine” that stretched beyond the frontiers of Jewish Palestine.50 Interpretations of biblical narrative scenes have also been discovered in the Land of Israel. The visit of the angels to Abraham was found at Sepphoris "

- ^ Henry Barclay Swete Introduction to the Old Testament in Greek Chapter 4: The Greek of the Septuagint

- ^ W. D. Davies, Louis Finkelstein The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 2, The Hellenistic Age 1990 Page 105 "Even in the expression of central theological concepts, such as that of love or that of the 'people' (of God), the LXX commonly uses the general terminology of its own time.1 Good examples of fairly colloquial Jewish koine can also be found in non-canonical writings like Joseph and Asenath or the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs... Nevertheless the LXX has something of a local atmosphere belonging to Alexandria. Some terms, especially those representing things and places known in Egypt, are rendered with customary words of the contemporary Egyptian linguistic usage; ... in Egypt, has effected the viability of certain choices of rendering in the LXX;1 but these are essentially a minor element in the ... Much more important is the Semitic influence upon the Greek of those biblical books which were translated from Hebrew (or Aramaic)"

- ^ A.-F. Christidis A History of Ancient Greek: From the Beginnings to Late Antiquity – Page 640 2007 "No ancient or medieval writer recognizes a distinct Jewish dialect of Greek. In particular, Jews themselves have no name for any “Jewish- Greek” idiolect (contrast later terms like Yiddish [Judeo-German] or Judezmo [Judeo-Spanish])."

- ^ Adam B. Jacobsen – Proceedings of the 20th International Congress of Papyrologists Page 57 1994 "Mark does reflect Semitic interference in certain regards (loan-word borrowings, semantics), but his syntax and style are largely free of it.39 While the editor of P.Yadin does not speak of a 'Jewish dialect' of Greek, I believe that in his ..."

- ^ Chang-Wook Jung The Original Language of the Lukan Infancy Narrative 2004– Page 11 "... or at other times 'a special Jewish dialect of Greek'. Cadbury declares with certainty that no spoken Greek by the Jews existed which 'differed extensively and uniformly from the language of other nationals'. He concedes that there are some ..."

- ^ Henry Joel Cadbury The making of Luke-Acts – Page 116 1968 "Septuagint and other Jewish Greek writings as well, seemed to represent a distinct dialect of Greek. The differences between the sacred writers were less than those which existed between all of them taken together and pagan Greek, whether the ... there is no evidence that Jews spoke a Greek that differed extensively and uniformly from the language of other nationals."

- ^ John M. Court -Revelation – Page 87 1995 "It is a first-century CE Jewish dialect of Greek, as used in Palestine ('distinguishable dialect of spoken and written Jewish Greek' — Nigel Turner; 'while he writes in Greek, he thinks in Hebrew' — R.H. Charles; 'Greek language... little more ..."

- ^ Natalio Fernández Marcos The Septuagint in Context: Introduction to the Greek Version of ... Page 343- 2000 "Christian Greek has to be studied as an extension of classical Greek on the one hand, and of biblical and Jewish-Hellenistic Greek on the other. Generally, it seems clear that it has fewer neologisms than Christian Latin.24

- ^ Christine Mohrmann Études sur le latin des chrétiens – Volume 3 Page 195 1965 "Early Christian Greek has, as point of departure, the Jewish-Hellenistic Greek of the Septuagint. During the first two centuries, Early Christian Greek develops very rapidly, and is distinguished from the general koinè by numerous semantic "

- ^ E. A. Judge, James R. Harrison The First Christians in the Roman World Page 370 " ... powerful Jewish community in Alexandria imprinted itself on the koine as seen in Egyptian papyri should also be carefully checked in the light of these cautions.9 A thousand years later there did arise a true Jewish dialect of Greek, Yevanic, ..."

- ^ Steven M. Lowenstein The Jewish Cultural Tapestry: International Jewish Folk Traditions – Page 19 – 2002 "From 3000 to 5000 Jews in the Yanina region (Epirus) of northern Greece who spoke a Jewish dialect of Greek, unlike the other Greek Jews, who spoke Judeo-Spanish (see group 3). 9. From 1500 to 2000 Jews of Cochin in southern India, ..."

- ^ Jacob Milgrom, David Pearson Wright, David Noel Freedman Pomegranates and Golden Bells: Studies in Biblical, Jewish, and ... 1995 Page 808 "On the pronounced paratactic character of the Jewish Koine, influenced by both popular Greek and Semitic Hebrew and Aramaic, see F. Blass and A. Debrunner, A Greek Grammar of the New Testament (trans. and rev. R. W. Funk: Chicago: ..."

- ^ Katrin Hauspie, Neologisms in the Septuagint of Ezekiel. 17–37. JNSL 27/1 in Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages – Universiteit van Stellenbosch

- ^ Johan Lust, Erik Eynikel and Katrin Hauspie. Greek-English Lexicon of the Septuagint 2008 Preface

- ^ T. Muraoka A Greek-English Lexicon of the Septuagint 2009 ISBN 978-90-429-2248-8 Preface to the 3rd Edition

- ^ The Greek and Hebrew Bible: Collected Essays on the Septuagint – Volume 72 – Page 140 ed. Emanuel Tov "There is another reason for a cautious use of the label 'neologism': a word described as a neologism on the basis of our present knowledge may, in fact, be contained in an as yet unpublished papyrus fragment or the word may never have been used in written language."

- ^ Tov "...Neubildungen is more precise..."